5 Wild Old-Timey Versions Of Common Household Items

We take many household items for granted every time we mindlessly and despondently tick off another godforsaken day on our calendars or plop down on our recumbent bikes for our daily six minutes of low-intensity cardio. But did you ever wonder how these conveniences came to be? No? Well, maybe you should because some of the most seemingly basic things in your home hide spectacularly zany histories behind their modern veneer ...

Cherokee Turtle Calendars

Calendars are the most marketable invention of all time. You can buy a calendar with anything you want on it, from happy kittens to random landscapes to (still, sadly) Dilbert. But to some tribes like the Cherokee, calendars only came in one flavor: turtle shell.

Don't Miss

Turtle shells have 13 inner scale segments and 28 outer scale segments, coinciding with the lunar cycle of 13 Moon-months consisting of 28 Moon-days. Or 13 full Moons per year, each separated by 28 days. It's a pretty sweet cosmic coincidence and a great example of humanity's innate need to find patterns literally everywhere.

A First Nations legend describes how the unassuming turtle received its divine temporal cognizance. Many moons ago, long before Creator peopled the Earth, the animals could talk. One day, Turtle and Raven exchanged pleasantries, and Turtle, lamenting his terrestrial limitations, wished to taste some of that sweet sky for himself.

So Turtle bit onto a twig, and Raven lifted him high into the heavens. But when Turtle opened his mouth to express his pleasure, he fell to the ground and shattered his shell. Creator took pity on Turtle and put its shell back together with the purpose of tracking the moons. Creator also bestowed long life on Turtle and made it the Keeper of Knowledge.

Apparently, Native American God is much nicer than Abrahamic God, who would have blighted Turtle's family with boils or a similar pox.

Huge Vacuum Cleaners That Wheeled Up To Your House

In 1901, English engineer Hubert Cecil Booth invented a motorized vacuum cleaner, forever freeing women from the drudgery of beating rugs with a cudgel. But this revolutionary invention wasn't a thing you wheeled around your house; it was a thing that was wheeled to your house.

Booth was inspired while watching a demonstration of a new cleaning machine at the Empire Music Hall in London. But this machine was more leaf-blower than vacuum, and Booth ambitioned to create a suction-based cleaner.

Booth even (allegedly) almost choked to death while testing the principle of suction-based cleaning by putting a hankie over his mouth (as a filter) and sucking dust from an armchair. But that might be apocryphal because it's hilarious to imagine Booth (an engineer who built bridges, designed Ferris wheels, and invented engines for Royal Navy battleships) getting down on all fours to suck dust like some public transport pervert inhaling a young lady's ass particles from a bus seat. Regardless, Booth then started the British Vacuum Cleaner Company and invented the "Puffing Billy," a horse-drawn, piston-pumped, petrol-powered, five-horsepower-pushing behemoth.

via Wiki Commons

Booth and his crew of white-liveried vacuum technicians toured the wealthier neighborhoods, charging people (the equivalent of a year's wages for a junior maid) to clean their house. Puffing Billy couldn't fit indoors, so Booth's men would pull its long hoses through the window.

It soon became a trendy service. And fashionable rich ladies hosted "vacuum tea parties," serving tiny sandwiches and Earl Grey, with Puffing Billy noisily and angrily snuffling about their feet like a truffle hog. All the while, crowds outside marveled as a typhoon of dirt and skin cells swirled inside a glass chamber (Booth was no marketing dummy) for all to see.

Booth's invention quickly gained fame, and he was soon invited to clean Westminster Abbey for the coronation of Edward VII and Queen Alexandra in 1902. Booth was also commissioned to clean the Royal Mint and even sucked up 26 tons of grime from the surprisingly filthy Crystal Palace. The new monarchs also bought two Puffing Billys of their own, one for Buckingham Palace and one for Windsor Castle.

Booth's device wasn't the first vacuum—granted, the first was a hand-cranked device and not a petrol-fueled beast of a suck-machine—but his fantastic invention earned him status as "the father of the vacuum cleaner." And probably his pick of the finest big-booty hos of the Edwardian era.

Exercise Machines Got The Job Done

Dr. Gustav Zander was one of those innovative, enterprising minds born a century too early. The 19th-century Swedish physician lacked the negligent quackiness of his contemporary, leech-and-vibrator-obsessed "physicians" and forever revolutionized fitness.

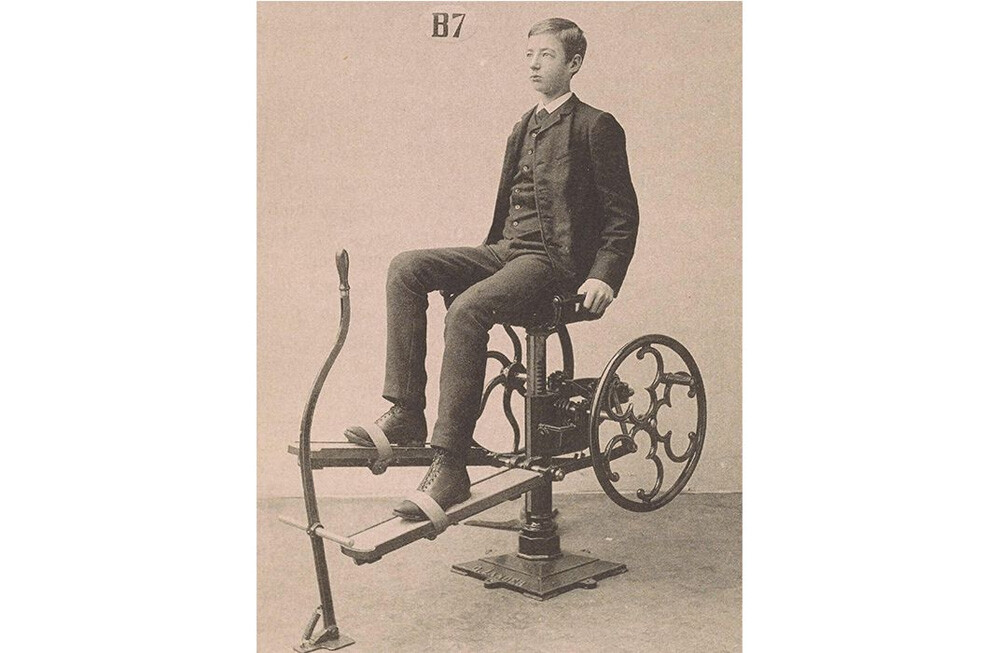

Zander pioneered the use of exercise machines to improve general health and treat physical impairments, especially the spinal deformities so common in the pre-Flintstones vitamins era. This, for example, was a scoliosis-stretcher:

In the 1850s, he developed various resistance-training equipment that was the first to implement the cornerstone of physical exercise: progressive overload. By moving the weight closer or farther along with a lever, resistance could be decreased or increased based on each individual's capabilities.

Zander earned his physician's license in 1864 and soon opened the world's first Gold's Gym, the Medico-Mechanische Gymnastik (medical machine gym) in Stockholm. After some initial skepticism, even hostility, from other health "professionals" (a generous term for the century), his peers eventually accepted his work, and in 1880 he established the second Zander Institute in London.

Some of Zander's devices have since gone out of style, like the "respiration machine" on which people presumably just sat and breathed:

And this goofy, vibrating, horse-riding simulator:

But some of Zander's inventions are still widely used today, including a gym-staple, the stationary velocipede (everything had a badass name back in the day), aka bike:

Some Zander machines, like the hamstring curl, remain unchanged more than a century later:

He even invented the leg adduction machine that inspires so many secretive glances from gym perverts:

And the most-used machine at any gym, the bicep curl:

But not all his inventions were equally practical. This now-obsolete “ab-kneading” machine presumably trained heavy drinkers to withstand pub-brawl gut-punches:

And his abdominal vibration machine preempted the vibrating ab-belt craze by more than 50 years:

Zander’s revolutionary machines received acclaim across the pond as well, and several were included at the Fordyce Bathhouse in Arkansas. And in 1911, Viennese doctor Kurt Linert ordered 36 Zander machines for The Homestead, a famed spa in Hot Springs, Virginia.

If not for the fact that Zander died in 1920, smack-dab between World War I and the Great Depression, he might be better remembered today. Instead, he languishes in the annals of obscure fitness history alongside electrical ab-belts and that kid who was really buff.

Salt Shakers Were Works Of Art

Historically, salt was worth its weight in gold and old-timey people stole, killed, and banged to attain this once-rare food preservative and seasoning. So, obviously, they couldn’t store something so exotic in any old Scooby-Doo shaker, so extravagant “salt cellars” were designed.

In the 15th century, the Portuguese arrived in West Africa and established trading stations, exchanging copper, brass, and textiles for spices, ivory, and eventually slaves. The Edo people of the Kingdom of Benin (now Nigeria) immortalized these encounters in the form of salt cellars crafted in the likeness of their undeserving European visitors, melding African art styles and European aesthetics:

And salt was such a big deal in Europe that those dining with the English monarchy were required to rise and stand at attention when the salt vessel was brought out—as if welcoming an Imperial general recently returned from waging genocide against the innocent, kindly colonial natives who welcomed him with open arms.

And there’s no grander royal salt vessel than the Exeter Salt, or Salt of State, probably the only salt container in history to earn inclusion into its country’s collection of Crown Jewels. It was presented to the newly restored Charles II as a coronation gift. Crafted around 1630 by Johann Hass, a goldsmith from Hamburg, it was given to his kingliness by royal goldsmith Sir Robert Vyner, on behalf of the city of Exeter.

The Exeter Salt is made of gilded silver and studded throughout with an embarrassment of precious and semi-precious stones, including emeralds, rubies, sapphires, and turquoises. The top screws off, revealing the salt within, and little drawers in the base would have held spices. The details are just as splendid as the jewels. Gilt dragons perch atop its ball-feet and a battery of cannons sits beneath its stately, crowned dome.

But the most Classically divine salt cellar was the Salera, crafted by Benvenuto Cellini, a sublime 16th-century Florentine goldsmith and sculptor. It’s considered by some the finest Mannerist artwork ever created.

Cellini was asked to create the Saliera by art-fiend Cardinal Ippolito d’Este, who weaseled out of the deal when it became too costly, but introduced Cellini to a far wealthier patron: the king of France, Francis I. Cellini hand-sculpted the salt cellar from rolled gold and gave it an ebony base with ivory bearings so it could move around.

It’s stupid with symbolism and on one side features the sea god Neptune, sea-horses to represent the tides, and a boat made for holding salt. On the other side, the earth mother goddess Tellus reclines in a most… titillating fashion next to a grand temple built to hold peppercorns. Around her, plants bloom, and animals gather in Disney princess fashion.

Cellini enjoys double distinction for also birthing the second-greatest Mannerist masterpiece, an autobiography so ridiculously vainglorious it resembles a Young Jeezy song more than a work of non-fiction. In it, the mad goldsmith boasts of having committed numerous murders, effecting a jailbreak, and fending off multiple armed robbers with his swashbuckling prowess, when they tried to steal the basket of gold he received from King Francis’ treasurer after completing the Saliera.

A Utensil For Everything Imaginable

Dining etiquette was vitally important to Victorian eaters, who developed a mind-boggling range of eating utensils more diverse than the roster of Marvel Vs. Capcom 2. Each place setting at a well-to-do dinner party may have included 20 or more total utensils, such as asparagus tongs and nut picks, to supplement a double-digit variety of spoons, knives, and forks of different shapes, dimensions, and decorations.

Literally every type of food had its corresponding utensil, including pickles, bits of cheese, nuts, and other small items that we now finger straight from the container, as it rests on our stomach, while we binge-watch murder documentaries.

Even soups required certain spoons based on their consistency, be it brothy, creamy, or chunky. And each fruit and vegetable had to be served with specific flatware: pickle forks, lemon forks, strawberry forks, lettuce forks, baked potato forks, tomato spatulae, and so on. One luxurious, straining-hole-studded son of a bitch was only used to serve cucumber slices.

Diners couldn’t even pluck grapes by hand. They had to use grape shears, designed with short blades and long handles to allow you to adroitly maneuver them within a grape cluster and snatch the juiciest morsel right from under the nose of Lord Higginbotham-Birdwhistle:

Even seafood, though not as often enjoyed, featured a stupidly diverse arsenal of silverware. Should a bite of food evade one of your 27 spoons or forks, God forbid you touch it. Instead, a respectable gentlewoman or noble-sir was expected to push it onto his utensil, using this creatively named food pusher:

Multiple factors sparked this runaway proliferation of utensils. First, well-to-do Victorians prided themselves on their fussy table manners, believing it separated them from the gutter-dwelling riff-raff. And, often, their fancy silverware was the only thing separating them from the so-called lower castes.

Second, the Industrial Revolution ushered in an era of mass production, cranking out all sorts of fancy forks and spoons by the ass-load. And mining expansions provided an inexhaustible supply of silver and other metals. With access to all these raw materials, artisans enjoyed the demand and the incentive to cater to (and exploit) the ever-growing population of wealthy urbanites with more money than sense.

Finally, if we remember our Psych 101 correctly, and we believe we do, the prevalence of pronged and poky devices manifested repressed societal sex urges, likely Freudian in nature.

Top Image: Smithsonian