Ancient Greece Had Memes And 'Diogenes Washing Vegetables' Was Its Biggest

Contrary to the name, Ancient Greeks are typically celebrated for how incredibly forward-thinking their society was, introducing the world to such important concepts as philosophy, democracy, and buggery. But what stuffy scholars forget to mention is that these august ancestors had also mastered an even more crucial key to modern culture: the art of mimeisthai or, as we know it, sharing dank memes.

If you’d ask a historical Hellene to demonstrate their legendary storytelling skills, they wouldn’t regale you with a passage from the Odyssey or the Promethean myth. Instead, it’s likelier that they’d tell you the story of Diogenes Washing Vegetables, which most scholarly textbooks deliver like this:

Don't Miss

But, if placed in its proper historical context, it should land more like this:

Move over, rapping Shakespeare. The new benchmark for desperately cool teachers should be convincing Zoomer kids that the Ancient Greeks invented shitposting. Called chreia, quickie anecdotes like Diogenes Washing Vegetables served an almost identical purpose in ancient dialog as memes do in the modern-day. Being able to cleverly copy/paste chreia into conversations was considered a legitimate oratory skill, and Grecian citizens, especially students, would try to show off their antiqui-meme game for social clout. When not actively participating in ‘the discourse,’ Hellenes would also entertain/educate themselves by discovering new chreia, either by lurking in forums or reading collections of anecdotes curated by Ancient Greece’s finest Buzzfeed writers.

Raphael

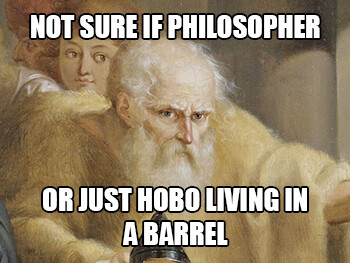

In fact, chreia are so closely related to internet memes that it’s almost impossible to explain the enduring virality of a Diogenes Washing Vegetables, which some scholars argue is one of the most quoted anecdotes in Ancient Greece and beyond, without looking at them like the meme’s oral tradition ancestor. As boring iconography nerds will point out, there’s more to memeing than just repeating some choice Socratic bants. To start, memes have their own language (in that it’s impossible to learn it once you hit 35) of formats and tropes. As literal literary devices, anecdotes effortlessly nail this requirement, with chreia going for extra credit by also going for speed and efficiency. Ancient Greeks knew exactly what they were in for when hearing a story start with “On seeing Diogenes ...” or “When asked, Diogenes …” in the same way someone doomscrolling would when seeing tufts of orange hair and “Not sure if” in 62pt Impact font rise from the bottom of their screen.

Equally important as playing by the rules is consistently breaking them. Memes have to keep spreading, and they achieve this, like any good virus, by inviting mutation as much they do on regurgitation. As such, a meme has to work both as a complete piece of entertainment and as a template, a paint-by-numbers outline of random Avengers scenes that lets you fill in Thanos with your classics professor and his thicc butt with the caption “enticing me to learn about Ancient Greece with memes.”

But how could chreia possibly achieve the same layering in Ancient Greek culture, where the spoken/singsongy word reigns supreme? It’s not like you can slap a macro on the spoken word. Yet chreia managed to do exactly that. Unlike with other types of anecdotes, misquoting wasn’t just allowed; it was expected. Orators would constantly change characters, backdrops, and other details to sync the chreia with the conversation topic. Sometimes Diogenes was dunking on Plato, other times on a pro-Dionysius noble like Aristippus. Likewise, Diogenes himself would be swapped out with another cynic or like-minded anti-establishment figure. Often, the story would feature neither Diogenes, Plato, nor King Dionysius, all those roles being filled by local figures the speaker wants to make a clever point about.

Despite these fundamental changes, the link to the original event always remained. Audiences were expected to know they were listening to the Diogenes Washing Vegetables story even if it didn’t feature Diogenes -- or vegetables. This worked because, in chreia, the template was the character’s rhetorical style, which had to be iconic enough that listeners didn’t really have to know the original context of the story to understand the reference. And like Condescending Wonka or Grumpy Bernie, Cynical Diogenes was (ironically) the Platonic ideal of a chreia character.’

As the world’s first celebrity troll, the real-life philosopher had an unprecedented understanding of how to make himself go viral -- aside from his habit of shitting in public places. A rhetorician, he employed an “eminently quotable” style that involved two strategies: A) dunking on other Hellenistic celebs as hard as possible (when offered a favor by a fanboying Alexander the Great, Diogenes asked him to piss off and stop blocking his sun), and/or B) firing off one-liners that sound deep but are just him Yakov Smirnoff-style repeating a statement but in the opposite order (when asked why he wouldn’t chase a runaway slave, he responded: “If the slave can live without Diogenes, Diogenes can live without the slave.”

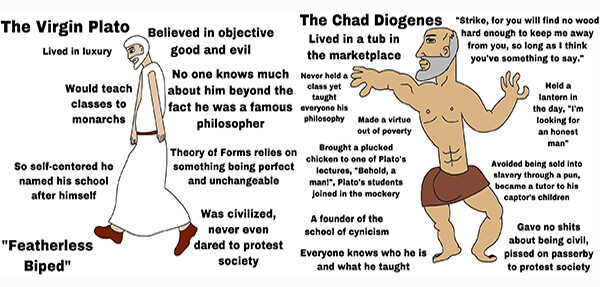

Universal History Archive

The only thing that could make a Diogenes meme even more popular is if he was paired with another famous chreia stock character: Plato, the Neil DeGrasse Tyson of antiquity. (His name is still a synonym for “unbearable know-it-all” in some languages). Tales of their feuds were the most epic crossover events in ancient history, with everyone in the Alexandrian Empire eagerly awaiting how the next classic franchise moments like the time Diogenes took a shit on Plato’s floor in the middle of a pretentious lecture, or the time he chased a plucked chicken into the academy after Plato had defined humans as “featherless bipeds,” shouting: “Behold! Plato’s Man!” And If that kind of comedy duo setup feels familiar, you’ve just discovered why Diogenes Washing Vegetables is a true meme. Because it, in barely two sentences, offers an elegant template to explore the universally recognizable dynamic of the aloof intellectual versus the principled everyman. The Scumbag versus the Good Guy. The Virgin Plato versus The Chad Diogenes.

Or, depending on your ethical stance, the Virgin Diogenes vs. the Chad Plato.

Because, of course, the true mark of this Macedonian meme is that a significant number of recorded variations of Diogenes Washing Lettuce not only tinkered with the format but completely hijacked it for political ends. In perhaps the earliest example in recorded history that the right can’t meme, Gordon Gecko Grecians flipped the order (oh, the irony) of the chreia so that now conservative Plato DESTROYS leftist Diogenes WITH LOGIC. Or toxic masculinity, at least, by having Diogenes first whine: “If you knew how to wash vegetables, you wouldn’t have needed to associate with powerful men” to have Plato (or another one-percenter) smack him down with: “If you knew how to associate with men, you wouldn’t be washing vegetables.”

And if turning the real-life story of Plato betraying his own philosophical principles by failing to stand up to the Syracusian tyranny of Dionysius II into a Diogenean comedy bit, then having that turned into a conversational blueprint for mocking elitists and sellouts and then having that turned into an edgelord dog whistle about non-traditional men being beta cucks isn’t indisputable proof that the Ancient Greeks were the first Meme Lords, I don’t know what is.

For more Hellenist memes for classical studies teens, do follow Cedric on Twitter.

Top Image: Mattia Preti