5 Strange Science Takeaways From The Middle Ages' Deadly Dance Hysteria

As more vaccines are administered and restrictions are lifted, it feels like we may finally be on the brighter side of the year-long nightmare we've been living. While we navigate our way out of the hell that we've been living through, let's take a moment to revisit a much stranger plague: Dancing.

Yes, there was a literal dancing fever so intense that it killed people in the Middle Ages ...

The Town That Couldn't Stop Dancing

Don't Miss

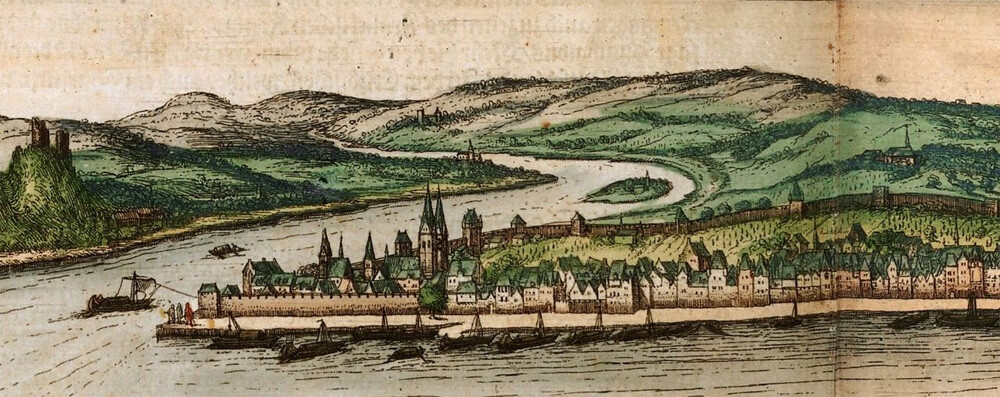

The most famous episode of this viral dancing occurred in Strasbourg in 1518, and it generally represents how a dancing epidemic played out. It began with one woman, a Dancing Queen, you might say, who is known only as Frau Troffea. She began dancing in the Strasbourg streets. There was no music and no cause for celebration; there was only dance. Her dancing seemed uncontrollable, and it just kept going.

Frau Troffea did not dance alone for long, though. As the days passed and her dance continued, other residents joined her. The dancing is often talked about like it was a virus, and that's because, in a lot of ways, it was. It spread through the town, and accounts say that 400 people joined Frau Troffea in her dance. From July to September, the dancers continued their hysteric performance. Their moves were unstoppable and often deadly, as many who continued to get down died from exhaustion, starvation, heat exposure, or any number of other possible afflictions that could come from weeks of endless dance.

This Wasn't An Isolated Incident

Strasbourg's dancing plague of 1518 is the most famous and likely the largest dancing mania incident in the Middle Ages, but it was a far more common occurrence than you might expect. The first episode of dancing mania hit Europe about five centuries prior, in 1021, in the German town of Kolbigk. According to legend, 18 dancers blocked a priest from performing mass on Christmas Eve. For doing this, they were punished with a year of endless dancing.

Now, as with many accounts from the Middle Ages, the chronicles of this being a supernatural happening are (probably) false, but the pattern of groups of people performing a dance that they could not escape from is anything but fictional.

In another incident of fatal choreography, 200 dancers were involved in an episode on a bridge over the Moselle River. According to accounts, the dancing force was so great that it led to the bridge's collapse, and all of the dancers were killed. Similar stories also spread throughout the Middle Ages as a sort of bogeyman (or boogieman in these cases). Dancing or acting in ways that were considered impious in general was perceived as dangerous in medieval society, so the act of doing so had to result in almost biblical consequences, like dancing until a bridge collapsed. However, even if the tales were used as moral panic fodder, the idea of mass groups of people dancing for weeks or even months on end was reality.

Pathology Of The Dance

As David Byrne once said while doing his own dance in the "Once in a Lifetime" music video, "Well ... how did I get here?" There is no definite answer to this, but there are sound theories.

At the time, of course, this was chalked up to demonic possession. Who could blame anyone for guessing this? Those afflicted were said to be in a trance-like state, and many of them cried out for help and were visibly in pain, indicating that the dance was not their choice. While the dancers may not have been the victims of dark magic, keep this pinned to the idea board, as it will be important later on.

One modern theory is that the doomed dancers were suffering from ergotism. Ergot is a type of fungus that grows on rye. Effects of ergot ingestion include hallucinations and tremors, and instances of ergotism in medieval Europe are well documented. While this theory does offer an explanation for why something resembling dancing occurred, it does not explain why the episodes lasted as long as they did. The 1518 dancing plague in Strasbourg may have lasted two months, while ergotism's effects typically do not.

A more complex take on the cause of the hysteria comes from John Waller, a medical historian. Waller notes the severe psychological stresses were at play in areas where dancing plagues occurred. Life in the Middle Ages was brutal and short, and this was especially true in the regions and times where dancing outbursts happened. Take Strasbourg in 1518, for example. These were people dealing with poor harvests, which meant even harsher living. Diseases like syphilis were also raging throughout the area. The stress of this eventually broke people like poor Frau Troffea down.

As for why they went with dancing as an emotional reaction, Waller also discusses the idea of the people acting out the beliefs that they held. In our modern world, we have been going through tremendous stress too, but you don't see anyone dancing their worries away (outside of those first few months of the pandemic where everyone did TikTok dances, but that was just out of boredom). In the Middle Ages, though, the people who lived in the areas affected by dancing mania had firmly held beliefs about spirits and demons. Possession felt as real to them as the cycle of the harvest. When times became too difficult, some people may have been psychologically beaten until they believed that they were victims of possession. Then, others joined as mass hysteria spread.

TL;DR: pre-existing beliefs + extreme stress = a dancing fever you can't sweat out

What's The Cure For Dancing Fever Then?

Well, it's not music, that's for sure.

During the 1518 dancing outbreak, authorities logically concluded that the way to end the nonstop party was to encourage the entranced dancers to keep going until they ran out of energy. They brought in musicians to give the dancers a soundtrack and essentially turned the afflicted Strasbourg into a music festival. Instead of ending the dancing plague, this just encouraged it to keep going. It was a good effort, though.

"Let them die then, it will be a mercy."

Instead, the dancing ceased in 1518 when the afflicted dancers were taken to a shrine for Saint Vitus, who was associated with dancing. Priests performed rituals, and this supposedly cured the dancers. More dancers were brought to the shrine, and they were "cured" of their dancing. Then, the dancing eventually just fizzled out, much as it does at the club once the night has gone on long enough.

It makes sense to believe that removing the afflicted from the dancing would help on its own. If the dancers were more inspired to dance because others were doing so, removing them from the dance would logically remove the drive to dance. Dancing plagues are examples of mass hysteria, where groups suffer illnesses or perceived threats together. In this case, the illness just so happened to be dancing.

Has Anything Similar Happened Since Then?

There have been about 10 documented instances of dancing plagues that occurred during the Middle Ages. These are only the ones that have been documented, so there is always the chance that other incidents occurred. One thing remains certain, though. Once dancing plagues went away, they went away for good. There was never a moment where people in Germany joined an endless dance circle in 1800. Much like many styles of dance, dancing plagues were really a product of their time.

As seen in this documentary, showing one that occurred in the early 2010s.

The reason for their decline may be linked back to the idea that the afflicted people danced in part because they believed demonic possessions were occurring. Mass hysteria is nothing new and has happened since the dancing died, but mass hysteria of this type was an incredibly localized thing to this era and location. As John Waller theorized, the circumstances of distress were all around the people of the time. It just so happened to manifest as dancing for them.

The dancing plagues of the Middle Ages continue to be some of the more fascinating and bizarre anecdotes of history. We may never know exactly what led these people to dance themselves to death, but it's also important to remember that we modern folks really aren't any less "crazy" than Frau Troffea and company. We have our own versions of mass hysteria. Remember 2016 when everyone claimed to see killer clowns? Or how about this past year where people nearly killed each other for toilet paper? The bottom line is that mass hysteria has always happened and probably will always happen. It just so happened that in specific circumstances, people at least got to party while losing their minds.

Top Image: Pieter Breughel