4 Famous People Driven Insane By Ayn Rand

Ayn Rand is unfortunately still popular, because reading good books is hard. She's best known for Atlas Shrugged, a boring lecture on the tenets of objectivism disguised as a boring novel. Objectivism, if you don't want to read the angry 5,000 word comments that spawn whenever Rand is mentioned, boils down to the belief that pure self-interest is the highest ideal humanity can have. Any political or religious obstacle that holds someone back from achieving their true potential must be destroyed. That can help justify eating your roommate's ice cream, but the idea starts to stall out when everyone in an unregulated market lets roads rot because they're always someone else's problem.

Rand's bugaboo was altruism. It's fine if someone wants to give to charity or run an orphanage, but the moment the government asks you to pay taxes you're living in a police state. In Rand's world, the government has no role beyond maintaining a military, police force, and court system. This is also where Rand falls apart, because her insistence that humans are born as blank slates tricked by nefarious societies into committing acts of selflessness crashes against the remedial rocks of evolutionary biology and history.

Don't Miss

But what is this, the goddamn New Yorker? We're here today because a bunch of Rand-worshipping bozos fought reality and lost, or at least made asses of themselves. So let's look at some asses.

Ayn Rand Inspired The CEO Of Sears (To Ruin Sears)

In academia, Rand's reputation is about level with phrenology's. A Rand biography wrote that critics "dismiss Rand as a shallow thinker appealing only to adolescents" and, perhaps not coincidentally, celebrities are big fans. But a lot of people only cite Rand as an influence because she's trendy, or offers superficial thoughtfulness. Angelina Jolie saying that Rand makes you "re-evaluate" your life doesn't mean she's going to found the underwater libertarian paradise of Joliesberg. Hell, if you're a Republican, Rand is one of the few authors you can like without your electorate calling you a communist for knowing how to read.

Aaron Burden/Unsplash

But it gets sketchy when Rand is applied to the business world. Atlas Shrugged is about how indomitable titans of industry are society's real underdogs, a worldview that someone paid to improve Home Depot's quarterly revenue can appreciate. It's often still a simplistic fandom; Mark Cuban said The Fountainhead inspired him to work hard and own his mistakes, but he didn't structure his life around it. And thank Christ, because leaders who really embrace Rand tend to have the touch of Midas' inept jackass cousin.

In 2008, Sears was struggling. But that was okay, because Eddie Lampert -- the "Steve Jobs of the investment world" -- was CEO. His solution: skim Rand CliffsNotes. Lampert split Sears into divisions ordered to selfishly compete for his time and money, because he believed that with only their own self-interest to pursue each division could achieve record profits. What really happened would have been written out of The Wolf of Wall Street for being too blunt.

His hairline alone would be dismissed as a cartoon fantasy.

Sears became 40 duchies that all saw themselves as the true claimant to the retail throne. So rather than the heads of different product lines all using the same marketing department -- which is how a sane retailer works -- the appliance department, tool department, clothing department, etc. all did their own marketing. Dozens of expensive CMOs were brought on to perform the same task.

Because the departments were only evaluated on their profits, no one could afford to care about the whole company. The divisions instead treated each other as bitter rivals to the point where executives hid their laptop screens in meetings. The apparel division cut salespeople on the assumption that customers would force salespeople from other departments to pick up the slack. Divisions wouldn't promote Sears' in-house brands, like Kenmore and Craftsman, because it was cheaper to sell competing products. Departments had to bid for flyer space, leading to a Mother's Day ad for a boy's bike. Customers were no longer enticed to visit with discounts because any department offering one would take a hit to their bottom line.

Store infrastructure decayed, workers protested, bed sheets were hung to hide empty shelves. By 2012, Sears was named one of America's worst employers, probably because of the reports of screaming matches and their "climate of fear." By 2017 you could read "Inside Sears' death spiral." Under Lampert's reign, a 120-year-old brand had to navigate bankruptcy court after losing half its value and most of its stores. Naturally, he's still worth over a billion dollars and owns a yacht called Fountainhead, because if there's one thing Rand definitely loved it was rewarding the incompetent.

The Co-Creator Of Spider-Man And Dr. Strange Created (Terrible) Objectivist Superheroes

Steve Ditko worked at Marvel before they were even called Marvel. He helped create Spider-Man and, more importantly, he made him unique. While Bruce Wayne was a billionaire playboy and Clark Kent a beloved reporter in a world too dumb to spot his obvious secret, Peter Parker dealt with bullies, self-doubt, and the perpetual fear of having his alter-ego exposed. Ditko's early control of Spider-Man gave him the humanizing flaws that make him great.

Ditko was also crucial to the development of Dr. Strange and his psychedelic landscapes; Marvel's pop culture empire would be a lot blander without his contributions. Famously reclusive, he left Marvel in 1966 and did his last interview in 1968. He kept working in comics and later returned to help create Squirrel Girl, but after Marvel he was free to go wild, even when he really shouldn't have.

Rand was in vogue in the ‘60s, and Spider-Man's disdain for student protestors showed hints of Ditko's fandom. Arguments with Stan Lee over Parker's development kept Ditko from turning him into an obnoxious Rand-quoting teenager, so enter Mr. A.

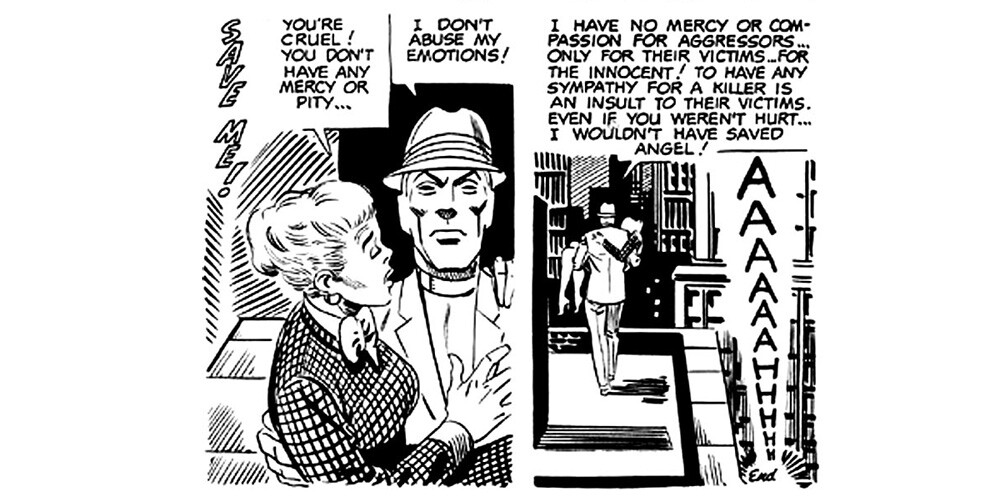

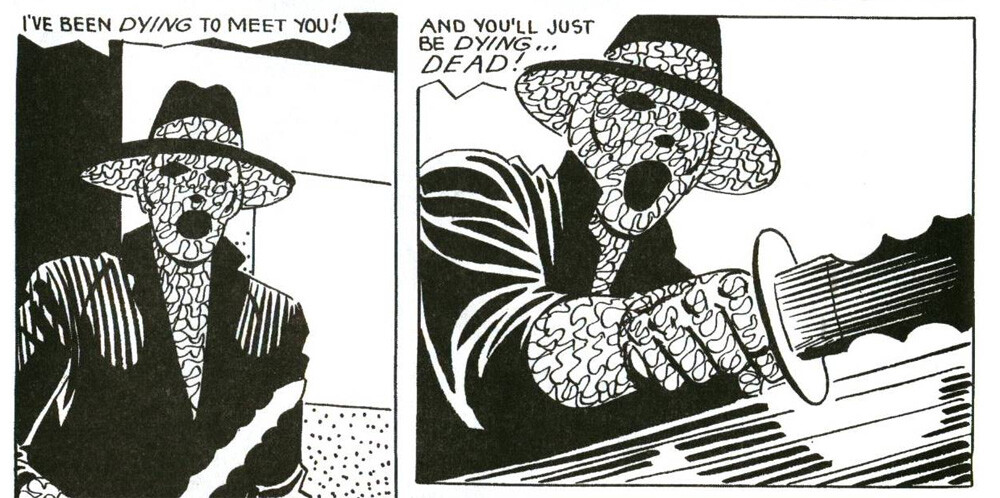

In Mr. A's 1967 debut, he forces a woman who's just been stabbed to choose whether she or her attacker should be saved, then harangues the woman for her naive philosophy as the teenage villain she thought was her friend is left to plummet to his death. His name is a reference to a line from Atlas Shrugged which reminds readers that moral grey areas are for pansies.

Mr. A tended to murder criminals or, worse, lecture them about the beauty of the free market. The thin plots often grind to a halt for his monologues, because one of the key tenets of objectivism is that morality plays must make Goofus and Gallant look nuanced. In this world, bank robbers opine on the morality of force before Mr. A disproves their philosophy while beating the crap out of them. His "anyone who doesn't agree with me is scum" worldview probably isn't hitting theatres anytime soon.

Wonderful Publishing Company

Ditko also created The Question, who's basically the indie Mr. A toned down for mainstream comics. If these characters sound familiar, that's because Alan Moore's Rorschach was inspired by how much Moore loathed them. Rorschach is a miserable jackass and, by all accounts, Ditko was too. He wrote paeans to his objectivist genius by night, and ground out potboiler crap like Chuck Norris: Karate Kommandos by day.

Ditko refused interviews because he insisted his work stood on its own, then sold mail-order essays about how he was misunderstood. Refusing to explain yourself well and then getting mad when people don't agree with you is arguably objectivism in a nutshell, and Mr. A is so tedious and arrogant it's unlikely he won over many converts.

Wonderful Publishing Company

The man stuck to his guns -- after decades of hack work, Ditko turned down a chance to reunite with Lee in 1992 because he didn't like the proposed project's "philosophical underpinnings" -- but there's something grim about seeing a talented man freed from oversight producing, well, this:

Rand Fandom Made Penn Jillette Act Like An Obnoxious Teenager

Not every Rand fixation has to end in tragedy or disaster; it can merely be embarrassing. And, like many embarrassing things, we begin with magicians. Penn & Teller are most famous for their long running magic act, and their old TV show where the hardcore skeptics used their critical eye to prove that second-hand smoke is harmless and taxes are the greatest evil in human history.

They're both Ayn Rand fans, although Teller has the good sense to stay, ahem, quiet about it. But as Jillette's video where he simultaneously points out some of Rand's personal flaws while saying "I would have f---ed her" suggests, his objectivism led him to some strange places. Most notable is his paean to his own genius, God, No!, which Jillette wrote like a 14-year-old who discovered atheism and masturbation on the same glorious day.

One of the criticisms of objectivism is its arrogance; no one advocates for a world dominated by supermen while picturing themselves as an irrelevant peon. And maybe that's how a talented magician ends up thinking the world needs a book bragging about his wealth, fame, and sex life. A non-believer like Rand, Jillette keeps insisting that he's more rational than all those religious sheeple, then makes himself the hero of a story where he threatens a social worker.

If anyone ever tells you that it takes a keen mind to appreciate Ayn Rand, show them Jillette's book. It's hundreds of pages of "The government is stupid! Those idiots who teach public school don't get nearly as much ass as me! I've slept with hundreds of women, and some of them even said they enjoyed it!" He hasn't changed much since writing this; interviews with Jillette continue to give the impression that he randomly shouts observations like "As an objectivist I'd like the Egg McMuffin combo because I need sex fuel, and by the way God doesn't exist, you idiot" whenever he uses the drive-through.

Atlas Distribution Company

Jillette's shtick is that he has the edginess of a child who just discovered that profanity makes some adults uncomfortable, but he also spent years presenting himself as a genius skeptic trying to make the world more rational. He insisted that his was the only reasoned worldview and we'd all be smarter if we listened to him, while simultaneously, say, calling Lindy West a "f---ng talentless c---" because he didn't like some jokes she wrote about Super Bowl commercials.

Coincidentally, another flaw with objectivism is its adherents' belief in the unique rationality of their framework. They'll tell you they have the only philosophy unfettered by dogma, and if you disagree then you just have to read their favorite books until you realize they're right. And that can lead you to the sad place where Jillette wound up, rambling about how criticism of him will create a world where it's illegal to read Ulysses. He's a good reminder that people who think they're always the smartest in the room usually don't enter very interesting rooms.

Silicon Valley Loves To Cherry Pick Ayn Rand

In Rand's work, a happy ending is when successful people swat aside whiners to get even more money. Not surprisingly, she's big in Silicon Valley. Travis Kalanick, who invented a taxi company that dodges responsibility for sexual assaults, is a fan. So is Brian Armstrong, who asks Coinbase employees to not be political about the cryptocurrency pyramid scheme that uses more electricity than Ireland. And of course there's Elon Musk, who's hard at work saving humanity with ideas like "What if roads were useless death traps?"

Uber was riddled with scandals under Kalanick's reign, Musk is famous for profanity-riddled tirades and random "rage firings." As attractive as the idea of a messianic businessman can be when you're the one who gets to play Capitalist Christ, running a business inspired by Ayn Rand is like becoming a detective inspired by Sherlock Holmes. The stories are dramatic, but "be a genius" doesn't tell you anything about the actual work.

In Rand's defense, the average reading of her is superficial. Her heroes are supermen, but part of that superiority comes from their sense of justice. A Randian hero demands hard work, but also rewards it; ignoring a toxic workplace or firing people because you're grumpy would get you an angry ass-kicking from Mr. A. Whether you want a world where CEOs are the ultimate arbiters of justice is another matter, but Silicon Valley's worship of Rand is like making Captain America your role model because he gets to beat up people.

Rand's heroes are cartoonish because they're impossibly incorruptible. It's like letting the fox guard the henhouse because all the hens will be impressed by how just the fox is. Anyone who thinks otherwise just doesn't know what's good for them, which is why Atlas Shrugged is about a world ground to a halt by ceaseless taxes and regulations. Titans of industry and science abandon America, but prepare to rebuild it as the inept government collapses.

Meanwhile, Silicon Valley's billionaires are avoiding regulation while paying less taxes than ever. And yet they have one foot out the door anyway; Rand-acolyte Peter Thiel, who helped inflict Palantir on us and really lived up to his libertarian ideals by suing Gawker into oblivion, has thrown money at the Seasteading Institute, which wants to build autonomous communities free from government oversight in international waters because they've never played BioShock.

Until that stupid day comes, Thiel can always retreat to his New Zealand apocalypse bunker. Bunkers are a booming business among the ultra-wealthy, fueled by the belief that they'll soon have to ride out a vague disaster that will allow them to re-emerge into a world where their wealth still means something.

The geniuses of Atlas Shrugged retreat to a community rendered literally invisible by magical sci-fi gibberish, and where the need for labor doesn't really exist. If a tractor breaks or someone needs surgery it's no big deal, because they plan to remerge and be lauded by society as heroes. Again, it's cartoonish -- Rand never really seems to accept that big ideas need people to execute them -- but everyone will supposedly be better off when our betters are put in charge of fixing the government's apocalypse.

In reality, our supposed betters think they might need to retreat from the problems they created. They don't talk about how to return and fix the world; they talk about using shock collars to keep their security staff from turning on them when "the event" comes. And there's maybe nothing less Randian than that level of uselessness.

Mark is on Twitter and wrote a much shorter book than Atlas Shrugged.

Top image: Steve Jurvetson, Bobbs-Merrill Company