There Was Once A Huge Empire Outside Of St. Louis, MO (And Schools Barely Teach It)

If you’re from a part of the world that doesn’t bother to teach American Indian history in schools (and that includes every part of the US that’s more than a ten-minute drive from a casino) chances are you’ve never heard of the Mississippian Culture, a once-great American Indian civilization that spanned across almost a third of the continental United States. And even those lucky few in the know probably had its thousand-year history crammed into one middle school field trip to a landfill outside of East St. Louis.

St. Louis Public Radio

Not that there is much more time needed to tell the story of the Mississippian empire as most of its history has been scattered like so many corn husks in the wind. And while it’ll take historians decades to puzzle together some of the only remaining pieces, what we can do in the meantime at least is to question the when, what, why and who behind the disappearance of the Mississippian Culture. (Spoiler alert: It’s white people.)

The Mississippians Were Corn-Fed, God-Fearing Sports Fans

It might be hard to wrap your head around a “Mississippian Culture” that doesn’t involve heated debates about the legality of riverboat pistol duels, but the ancient Mississippians actually had a surprising amount in common with the southerners who live there today. Leave aside the truck nuts and the hookworm and both of these sports watching, cookout lovin’, problematically religious southerners would’ve gotten along in an alternate universe.

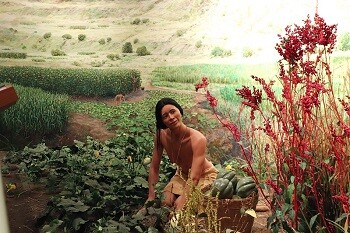

While centuries separate the fall of the Mississippian Culture and the rise of the S-- let us rephrase that. Despite having had no contact with each other, it’s remarkable how Mississippian the native Mississippians really were. Like the South, the MC started as a loose collective of different settlements whose common ideals allowed them to form a confederac-- let us rephrase that. These tribes eventually melded into a cultural coalition built on the most important southern values: slaver -- maize. Between the fertile Mississippi riverbanks and the MC’s advanced agricultural techniques, so much of the yellow gold could be produced that Mississippians went from a nomadic to a tribal to a grand agrarian society faster than a scalded haint.

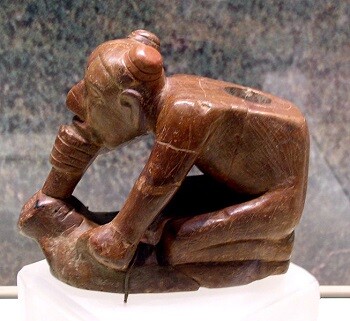

Even after everyone was as full as a tick, there was still plenty left to go around. Being the sharing kind, this allowed Mississippians to set up trade networks that brought back the most valuable riches from every corner of the continent. They received copper from the Great Lakes, jewels from the Sea of Cortez and even the most precious commodity of the Florida Keys: seashell necklaces. Equally important, the surplus of food allowed thousands of citizens to ditch the stone plows and become full-time artisans, taking great pride in turning these rare trade goods into some of the most coveted American Indian art ever seen.

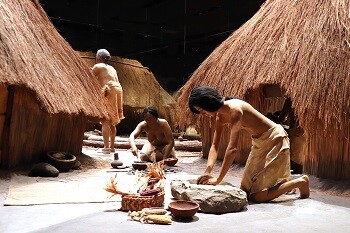

So what was everyday life like for the average Mississippian? Most farmers and tradesfolk lived in either one-deer towns or neatly planned suburbs near the big cities. Whenever they weren’t running all over hell’s half acre, they’d spend their time dedicated to two pastimes: sports and religion. On holy days, Mississippians would go out in their Sun Day bests to attend worship held by their chieftain, the Brother of the Sun. There, they paid tribute to variations of what is now called the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex or “Southern Cult,” a shared series of religious practices focused on cosmology. It had also gathered a colorful collection of mythic beings from the corners of their empire, from lawful gods on high like Red Horn, AKA “He Who Wears Human Heads as Earrings” and the mighty thunderbirds to netherworld stirrers of chaos like the Corn Mother and the terrifying underwater panthers.

But while modern Mississippians often have to choose between going to church and watching the game, the original Mississippians had them beat: watching the game was part of going to church. Of all the religious rituals, the most important was perhaps chunkey, a competitive spear-throwing sport where entire communities would travel to the city to see their varsity kids make the town proud by throwing the tightest spiral.

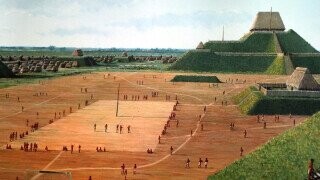

George Catlin

More importantly than being southerners, Mississippians were hillbillies -- in that they loved hills as much as any goat does. Inspired by myths of their ancestors, Mississippians built incredible earthen monuments. The greatest of which, Monks Mound, is over 100 feet high, wider than any Egyptian pyramid and required the transportation of over 22 million cubic feet of earth in handheld baskets. Their incredible engineering skill also covered city planning. Unlike other higgledy-piggledy Medieval cities, Mississippian cities had neatly organized neighborhoods that gave way to grand public squares and symmetrical monuments. These sights were complimented with circles of tall poles called “woodhenges,” which not only served as accurate astronomical calendars but were likely also used by architects to survey the city and keep that Midwestern city grid as perpendicular as possible.

Mississippian Cities Threw The Best Parties

It’s through these urban centers that modern people can recognize the power of the Mississippian Culture -- especially in Cahokia. As the MC’s seat of power and religious center, Cahokia was the greatest city American Indians ever created, serving as a blueprint for all other Mississippian city-states. At its peak, the six-square-miles wide, 120 mounds-rich city counted more than 20,000 citizens, making it larger than contemporary Paris or London and any North American city for the next 500 years until the expansion of Philadelphia.

Despite this, Western scholars didn’t acknowledge Cahokia’s status as a metropolis until the 20th century. Why? Because it lacked the one thing (white) historians deem necessary to describe a place as civilized: a marketplace. Mississippian cities possessed a vast trade network, so scholars were baffled why they hadn’t bothered to create a dedicated area for trade or any kind of currency -- because you’re only properly civilized once you can capitalism. But by holding onto these Old World historical prejudices they failed to recognize the source of Cahokia’s immense socio-economic power: its reputation as the Party City.

Cahokia remains one of the only cities that had to build an urban society from scratch instead of shamelessly cheating off the Mesopotamians. So the city set its own priorities: instead of material capital, they amassed social capital; and in place of a marketplace of goods it hosted a marketplace of ideas. The center of Cahokia was dominated by a huge public square, the ultimate hub for social gatherings. Citizens, suburbanites, and travelers alike would come to the square to share ideas, talk religion or stand in awe of the Mississippian elite orating from their mounds.

And those were just the Tuesdays. When it was time for a religious event, Cahokia could out-Mardi Gras New Orleans, out-Spring Break Lake Havasu and out-Hospitality State the whole of Mississippi at once. During these epic religious ceremonies (sometimes of the human sacrifice variety), the main plaza would swelter with over one thousand of the South’s most esteemed guests, each dazzling onlookers with their red-carpet-worthy hairdos, tattoos, and fancy feathered outfits. There and across the dozens of smaller plazas, celebrants would bet on chunkey games, participate in elaborate feasts (one particular rager saw Cahokia BBQ 2,000 whole deer) and get screwed up. Between smoking raw tobacco, a powerful psychedelic, and drinking a hyper-caffeinated tea called black drink, Cahokians would boot and rally throughout the festivities -- which could often take several days.

And the Mississippian rulers were very invested in being the hostess with the mostests as this allowed them to reach a whole new level of importance. Part of the religious celebrations typically involved all the worshippers to help construct or upgrade a mound. (Imagine an Amish barn raising but everyone is on meth). The more people showed up, the higher the mound. The higher the mound, the closer the mound-meister got to the Sun. The closer to the Sun, the larger their shadows stretches over those beneath them.

At its peak, about a third of Cahokia's citizens were immigrants from other American Indian civilizations, making it the “first pan-Indian city in North America.” Even those who didn't stay expanded the empire by spreading the Mississippian dream of having a mound with a white picket fence of your own at home, showing the folks enough beautiful souvenirs to prove it wasn’t all just a black drink dream.

The Mississippian Culture Collapsed Because Of Climate Change

For half a millennium, the empire of maize hit stride after stride, soon becoming one of the most powerful civilizations in the Western Hemisphere. But eventually, the population density of the Mississippian centers became a curse instead of a boon when something terrible sailed into America on winds from the east, something that would leave a trail of suffering and decay throughout the land for centuries.

William H Powell

Actually, for once, this calamity wasn’t in the shape of a white guy with a plumed hat and a farmer’s tan. When, in 1540, famed Spanish explorer and disrespect of borders, Hernando de Soto, and his reaving band of conquistadors arrived in the heart of the Mississippian Culture all they found were some quibbling tribes and ruins. What the European colonists didn’t realize was that Cahokkia had already crumbled a good 200 years prior, a victim not of colonialism but the frosty deathblow of climate change.

For centuries, historians assumed that the Mississippian cities had simply collapsed under their own weight, a classic tale of heathen hubris and biting off more maize than you can chew. But the most popular theory today is that the real Cahokia killer was likely a long cold streak. Experts now believe that the world’s Little Ice Age started in North America in the 13th century and, true to their nature, Mississipeans coped with this long winter as well as a Texan driver when they see a single snowflake land on the road. As the cold gave way to floods which gave way to droughts, maize cultivation took a serious hit. Before long, this Husk Bowl made city farmlands unable to maintain their vast populations -- a crisis Mississippians resolved in two ways: mass migration and murder.

As the MC’s prosperity declined, so did the power of its ruling class. Scholars wanting to avoid the oversimplification of “cold done did it” will point at corpse pits that show that the cities had their share of stabby seditions during the decline. Despite occasionally showing its people a really good time, Mississippian Culture was still a wealthy human civilization, i.e. it enforced a ruthless class system between the have-mounds and the have-not-mounds. From within now-walled inner cities, Emperors would routinely order around their subjects like mere slaves, forcing them to build bigger and bigger peat pyramids like some formicary pharaoh. Meanwhile, in a shocking first for the Deep South, the slick-talking, showboating Old Religion priests would not always redistribute their vast offerings to the poor, instead enriching themselves.

Hell, even dead one-percenters had a more privileged role at the height of Mississippian society than the average serf -- especially the one they had sacrificed and buried butt-to-butt with them to fend off the underwater panthers. Since the Mississippians regarded Cahokia as the prison plexiglass screen between the material and spiritual world, entire mounds and districts in the city were reserved for housing the dead. And the more upper-class Cahokians croaked, the more the living lower classes were squeezed into tighter and tighter quarters or driven completely out of their districts.

As the mass famine led to political discontent, urban life lost all of its pizzazz. City dwellers were forced to spread out again and form more manageable communities. This left Cahokia and other urban centers completely abandoned by 1350, their former inhabitants only returning to hold the odd religious ceremony. But the Mississippians weren’t giving up, they were just biding their time. Historians have recently found proof that a migration back to the cities had begun in … the 1500s. Crap.

Colonists Completely Scattered Their Culture

Surely, this couldn’t have been the end of the grand Mississippian Culture? As the name implies, it was never about the big cities. It was about the people, their mastery of the land and their enduring traditions. And to honor this legacy, the proud mounds of Cahokia still stand in America today. Specifically, they stand between the I-55/70 interstate and the Indian Mounds Golf Course.

While European settlers didn’t cause the death of the Mississippian Culture, they’re definitely responsible for burying it. If that sounds a bit dramatic: what if we told you that most of what has been written in this article is wrong -- for once consciously so? Every single name used to refer to Mississippian Culture, including Mississippian Culture, is a meaningless moniker made up by some dead white dude. Monks Mound isn’t the English translation of what the Cahokians called their most important place of worship, it only got called that after 1735 when Trappist monks started squatting on the monument and decided it should be named after them. So what did the Cahokians call Monks Mound? Nothing. Like us, they didn’t know anything thing about Mississippian Culture because Cahokia was the name of a tribe from a whole other confederacy; the European settlers just assumed those were the Indians who had lived there and named it accordingly.

But like we said, culture remains a part of peoples forever. After its decline, dozens of southern tribes still carried a piece of the conglomerated Mississippian Culture with them. It’s just that the chance of fitting them back together is close to zero, what with European Americans wiping out half of the pieces and forcing the rest to assimilate with another puzzle. Impressively, the Natchez tribe managed to hang onto their Mississippian cultural roots until the 18th century, when keeping up traditions was getting in the way of progress. Namely, they were in the progress of being slaughtered and enslaved by the French.

And those great platform mounds are no longer in any state to reveal their secrets either. Many collapsed after rampant American industrialism eroded the soil and flooded the plains. Others crumpled after locals dynamited the shit out of them to loot whatever was left of the burial chambers. Meanwhile, over half of Cahokia, that supreme religious nexus of the continent’s greatest civilization, was flattened and used as landfills so that St. Louis property developers could build housing complexes with a view. And if you want a perfect example of how little of a damn Yankees have given about messing with Indian American cultures, that they built a city on the largest Native burial ground in history and nicknamed it “Mound City” seems just right.

The Colonists Covered Up Their Culture Because It Clashed With The Narrative

If at this point it’s starting to feel as if non-Native American settlers and scholars went out of their way to not give an underwater panther-damn about recognizing the Mississippian Culture, contemporary historians may agree. The (lack of) cataloging of Mississippian history cannot be attributed to just bad timing and scorched earth colonialism, but likely to a centuries’ long attempt by the United States to tuck this civilization under its Bible Belt.

Until the late 20th century, listening to European-American historians describe Mississippians felt like listening to a Japanese whaler trying to convince you that a dolphin is just a dumb fish who has it coming. Scholars like Lewis Henry Morgan insisted on describing Mississippian Culture as a “Stone Age culture,” its followers as “Sun Set Indians” and its complex city-states as mere spread out tribes. Even the choice of the term “mounds” makes these gargantuan feats of terraforming sound like something your five-year-old climbs for his first t-ball game. When not downplaying the Mississippians’ achievements, Western historians instead tried to make them seem as bloodthirsty and dangerous as possible. Until the 1930s the Southern Cult was academically referred to as the “Buzzard Cult” or “Southern Death Cult.” This despite no evidence that the SECC’s ceremonial executions were any more gruesome than the religious killings documented in Medieval Europe.

When the grandeur of Cahokia and other monument cities became too obvious to ignore, scholars simply shifted to another problematic tactic of Anglo-American historical revisionism: “aliens done did it.” Specifically, in the 19th-century theories started flying about the “Mound Builders,” an unknown ancient civilization who must’ve created these wondrous mounds and woodhenges. Potential candidates included lost expeditions of Israelites, Hebrews, Greeks, Persians, Romans, Vikings, Hindus, Phoenicians or a conveniently lost true American civilization -- anyone except for these dangerous Stone Age Natives who, come to think of it, probably invaded and killed these swell Mound Builders anyway.

Why has U.S. history shown such disrespect to a fascinating piece of American heritage? Maybe it had something to do with the fact that the Mississippians were indeed dangerous. When de Soto and his army tried to claim the South for Spain, the “Mound Builders” sent them packing. When colonists then built a fort in Mississippian territory to establish a military foothold, the “Mound Builders” wiped out it and every other military outpost in a 100-mile radius with only one in every 200 European soldiers making it out of the MC alive. And this all happened in the 1500s. Even while crumbling to dust, the Mississippians were able to kick out colonialist carpetbaggers as few native people could.

Or maybe the real danger that the Mississippians posed was against the American narrative of the “savage Indian” who wasn’t really using America anyway. Sure, pre-colonial North America was full of unique and complex societies that the US bulldozed over without remorse, but Cahokia was different. It was a ‘civilization’ even by European standards. Acknowledging that would have meant Americans had to acknowledge that they didn’t just take the American Indian’s land but their potential for greatness too, and that their kids ought to be playing “Conquistador #3” instead of “Pilgrim #3” in future Thanksgiving plays. And while today the US is trying much harder to acknowledge, respect and repair its treatment of America’s first peoples, for the MC it might be too late. The Deep South Empire may finally get a place in the American narrative, but its story is all but gone and forgotten.

Cedric Voets is a writer and comedian and uncomfortably European.

Top Image: UNESCO World Heritage, Flickr