How Women Got To Wear Pants: The Dr. Mary Walker Story

Buckle up those britches, boys and girls, since we have a lot to cover. 19th-century gender equality pioneer Dr. Mary Walker battled lawsuits, starred in sideshows, and survived Confederate imprisonment with the same moxie that would eventually win her a Congressional Medal of Honor. She did all that while refusing to observe her era's fashion mandates and proudly touting the practicality of women's pants. She'd be the first to tell you it's tough to change the world without pockets.

Nobody Puts Baby in the Corset

Born in 1832 as the second-youngest of seven children, Mary Walker had a leg up in the pant game from an early age. Her parents, Alvah and Vespa, believed that their children, penis or no penis, should have equal opportunities in life. This also meant more responsibilities, and all of the kids helped out around the farm. Alvah understood that plowing a field was borderline masochistic while dressed in a corset, thus encouraged his kids to wear comfortable, practical clothing. He also believed that long, trailing skirts were unsanitary and prone to getting dirty, as anybody who has attended a music festival knows well.

Mary's parents also believed that all of their children deserved a professional education. This was not the easy road as there were five girls and two boys in the family. Complicating matters further, there was no appropriate school in the nearby Oswego Town. Naturally, Alva and Vespa continued their liberal streak and started the first free schoolhouse in the area.

After finishing with homeschooling, Mary and a few of her sisters went to Falley Seminary in nearby Fulton before becoming teachers. Mary saved her salary with a larger goal in sight: attending medical school.

That's "Dr." Mary Walker To You

The future fashion iconoclast became a full-fledged doctor in 1855 after a grand total of 39 weeks in medical school. The cost at the time was an understandable $166. That's equal to $5,018 in today's dollars, or about 1/4 the price of a used Honda Civic. After graduating with honors, Mary became the second woman with a medical degree in the United States after Elizabeth Blackwell. But Mary was cooler because she wore pants.

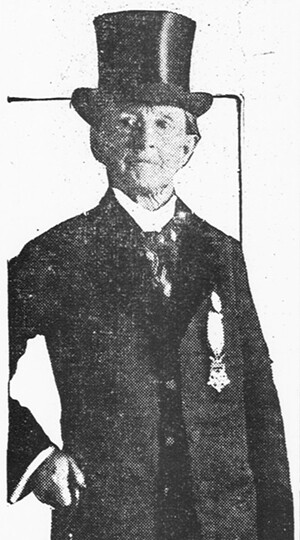

Classmate Albert Miller recognized the spark in the five-foot-nothing trailblazer, and just after medical school, the couple married. Never to fall prey to the fashion constraints of her time, Dr. Walker wore a suit and a top hat to her own wedding and refused to allow the word "obey" in the traditional "love and obey" promises of the ceremony. It turned out that hubby Albert wanted to omit the "love" part as well, as he allegedly had multiple affairs within a few years. Since this was the 1850s, divorce was hard to come by, especially when initiated by a woman. Mary took her next best available step of leaving the lying sod to flounder in their failing medical practice as she went to the great state of Iowa. Turns out over there, divorce was easier to finalize. Score one for corn country.

While wrangling the separation paperwork in the Hawkeye State, Dr. Walker attended Bowen Collegiate Institute, which would later become Lenox College before becoming entirely defunct in 1944. Mary must have seen the writing on the wall as she pointed out to the higher-ups that the college offered German classes but had no German instructor. She went about raising gender non-conforming hell at Bowen until she was suspended for refusing to resign from the all-male debate team (which seems to go against the entire concept of debating, but you do you, Bowen). Before she got the ultimate boot from the institute, however, she was able to gain the support of many male members of the club and the surrounding town of Hopkinton.

The expulsion, along with a letter from an attorney back east explaining that out-of-state divorces would not be recognized by New York state, ended Mary's midwestern sojourn.

A Soldier, A Prisoner, A Lady In Pants

At the start of the Civil War in 1861, Dr. Walker went to Washington, D.C. to offer her services to assist the Union. By this time, a few more women had medical degrees but still made up a paltry 1.6% of U.S. doctors. As such a minority in the field, they were often disrespected and relegated to assistant positions. Mary attempted to enlist as a field surgeon but was denied, as she explained, "solely on the ground of sex" -- an issue she later brought up with General Sherman and President Lincoln. She then offered her services to the War Department as a spy, again to be denied. While the doctor denial seems straight-up sexist, a spy lady in pants might have been too conspicuous to have been helpful.

Not finding a career either in espionage or surgery, Mary volunteered as a civilian nurse at a temporary hospital at the U.S. patent office. During this time, she made it her business to inform soldiers of their right to refuse amputation. From her years as a doctor, she knew how to examine patients and found, in her own words, that in "almost every instance ... amputation was not only unnecessary, but to me, it seemed wickedly cruel."

"We're never going to finish our leg fort with that attitude, orderly."

In between fighting the patriarchy and saving soldiers from wanton bone saw procedures, Mary somehow had the time to start the Women's Relief Organization. The group helped women travel to the nation's capital to visit wounded (and hopefully four-limbed) relatives. Her combined efforts eventually earned her a commendation and request for a formal position from her superior, which was again denied by the federal government. The underappreciated good doctor then went back to New York to earn yet another medical degree in hydrotherapy from Hygeia Therapeutic College. There we can only hope she learned that the mercury tablets and bloodletting treatments used in the field were less than helpful.

As the war dragged on, more casualties meant more job openings. (Try to look on the bright side, right?) The 52nd Ohio Regiment eventually hired our pantsuit protagonist as a civilian surgeon, the first woman in such a position in the United States. For both the North and South sides of the war, she became famous for her look of, well, a woman doctor in pants. As one Confederate saw it, she was, "A thing that nothing but the debased and depraved Yankee nation could produce. dressed in the full uniform of a Federal surgeon." So, you know, the second stupidest thing that Confederates believed.

Her famous look eventually came in handy when she was caught assisting civilians behind enemy lines and thrown into the notorious Castle Thunder prison. After a few months, she was traded in a POW exchange and returned to active surgeon duty. Whenever she had a break from the operating scene, she spent her time stumping for President Lincoln's reelection, despite his unwillingness to help her earlier in her career.

As we know, Lincoln got reelected and then got shot, so it was President Andrew Johnson in 1865 that awarded Dr. Walker the Congressional Medal of Honor. And despite her wartime bravery, keeping the medal became its own struggle. In 1917 a congressional committee stripped her achievement. They decided the medal was only for officers or those formally enlisted. Remember, despite Mary's qualifications, recommendations, and repeated requests for formal placement, she was only ever a civilian surgeon who happened to be on the front lines of the war.

Of course, Dr. Walker refused to return the medal and wore it proudly until the last day of her life. Eventually, someone in the Carter administration had enough sense to retroactively reinstate her award. To date, she is the only woman to receive the nation's top military medal.

Let’s Pants!

Before we get to Mary's escapades after the war, we should take a moment to explore the era's fashion. Upper- and middle-class women were expected to wear six to eight petticoats to give their silhouette the proper proportions (for the uninitiated, a petticoat is an under dress, not, in fact, a coat). The amassed fabric weighed up to 15 pounds and often led to health complications. Beyond hip issues, carrying a full chamberpot up and down flights of stairs while encumbered by a restrictive corset and billowing skirts had its own set of sticky hazards.

To rectify these issues and liberate women everywhere, an editor of the first women-centered U.S. newspaper, The Lily, promoted her wild idea: "Turkish pantaloons and a skirt reaching a little below the knee." While this editor did not invent the style, she was its strongest advocate, and so her last name was given to the design: Bloomers.

Dr. Walker favored this style of pants for several decades before moving onto even more transgressively man-style pants. Some suffragettes took issue with Dr. Walker's fashion choices, not because of the style of pants, but rather because of her "untidy hair, unwashed face, and dirty hands," and especially her "nose picking and nail biting." It was thought that such a slovenly presentation would hurt the women's rights movement. Mary didn't suffer such arguments and proclaimed, "I am the original new woman. Why, before Lucy Stone, Mrs. Bloomer, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony were -- before they were, I am. In the early '40s, when they began their work in dress reform, I was already wearing pants ... I have made it possible for the bicycle girl to wear the abbreviated skirt, and I have prepared the way for the girl in knickerbockers."

Dr. Walker, Congressional Candidate and Sideshow Star

The year after the Civil War, Dr. Walker was elected to head the National Dress Reform Association. From here, she fell out of grace with many leaders in the women's rights movement. One of her strongest beliefs was that the U.S. Constitution already granted women the right to vote; everyone had just not realized that little detail yet. Many ladies did not like Dr. Walker's caustic attitude and brazen viewpoints and essentially shunned her for the rest of her life. If you haven't guessed by now, Mary did not give a single damn. She continued on her own speaking engagements and published two books: Hit: Essays on Women's Rights (1871), and Unmasked, or the Science of Immorality: To Gentlemen by a Women Physician and Surgeon (1878).

As her connection with the Suffragist movement broke down, Dr. Walker needed a platform to spread her views and so joined a touring vaudeville sideshow. A force to behold, she stood on stage in a top hat and tails and regaled the audience with tales of her time on the battlefront. While she certainly enjoyed the chance to pontificate, her life was in a downward spiral. As one contemporary journalist observed, "There was a time when this remarkable woman stood upon the same platform with Presidents and the world's greatest women. There is something grotesque in her appearance on a stage built for freaks."

Throughout her final years, she managed to manifest controversies and stunts, like being arrested several times for "impersonating a man" or inviting Kaiser Wilhelm of Prussia to her family farm. She also caused a stir when she tried to vote in her hometown of Oswego. She was denied and then responded with this zinger: "I am a fe-male citizen and therefore a male citizen." Running on temperance and universal suffrage, she had two unsuccessful bids for Congress in 1890 and 1892.

Dr. Mary Walker died in 1919 at the age of 86, buried in her black suit and tie a few short months before women formally achieved the right to vote. She didn't need the world to tell her she was right.

Top image: U.S. Army, Library of Congress