The Murder Dollhouses That Changed Forensic Science

Frances Glessner Lee, the "mother of modern forensic science," led a remarkable life. She was a millionaire heiress, co-founder of the Harvard Department of Legal Medicine, the first-ever female police captain, and alleged inspiration for everyone's favorite crime-solving grandma, Jessica Fletcher. But above all, Lee will be remembered as the world's most influential arts and craftsperson and dollhouse maker.

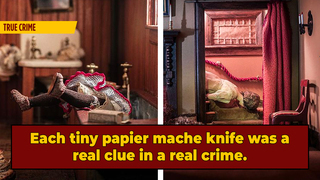

Because Lee's dollhouses came with a twist: inside the quaint little miniature walls, there had been a murder. Starting in the 1940s, the forensic expert began using her impressive crafting skills learned as an ex-housewife to create twenty dioramas she referred to as "Nutshells." Not out of place in Wednesday Adams' bedroom, these dollhouses contained a perfectly replicated crime scene, each doll a dead porcelain prostitute …

Or a murdered doll family of three ...

Or a miniature suicide, the victim still dangling from a piece of Michaels twine.

With an eye for detail honed by both crafting and detecting, her careful studying of crime scene reports and photos allowed the captain to recreate these tragic homes perfectly, from the blood spatters on the ground right down to the tiny food labels. Just in case it was relevant that the grizzly murder weapon was hidden specifically in a box of Count Chocula and not Booberry.

That's because these dollhouses weren't just for show or as part of some very elaborate craft therapy. The dioramas were intended to be a teaching tool for homicide investigators, each tiny papier-mache knife a real clue in a real crime. Armed with nothing but a flashlight and a magnifying glass, students of her Harvard department were given ninety minutes to crack the case of the burned felt skeleton or the doll with the cracked porcelain head at the bottom of the stairs.

More importantly, the Nutshells (each costing thousands of dollars in Hobby Lobby trips) taught future forensic experts to look with their eyes, not their hands; each dollhouse too tiny to trample on its evidence and taint its cute crime scene. As importantly to Lee, it also taught cops another skill: empathy, with Lee focusing specifically on crimes of a domestic nature, featuring the forgotten underclasses of society like women and the poor. In doing so, Frances Glessner Lee's tiny rooms made giant leaps in the field of modern policing, and she achieved it armed with nothing but a glue gun.

For more tiny tangents, do follow Cedric on Twitter.

Top Image: Lorie Shaull