Why Do We Even Have Batman Movies Today? The Joker.

Over the past 80 years, Batman's archnemesis The Joker has become one of the most recognizable fictional villains worldwide. It's not totally obvious why our civilization is obsessed with, of all things, a gangster clown, so this week Cracked's exploring the character's enduring popularity and what The Joker's many iterations reveal about us, the audience. Check out part one here.

It's difficult to impress onto those who weren't there the sheer cultural ubiquity of the live-action Batman films; that is, the series that began in 1989 and ended in the erotic fever dream that was Batman & Robin in 1997. The franchise arguably peaked in 1995 when you could play a Batman Forever video game on nearly every damn console, eat a Batman Forever-themed McDonald's value meal, and unironically belt out every single lyric to Seal's "Kiss From a Rose" -- which, in retrospect, were probably all about cocaine. Yes, in the post-USSR collapse, pre-"nigh everybody has access to the internet and can enjoy 90,000 other things instead" world, Batman Forever represented the aesthetic apex of America's brief run as the world's sole superpower. 300 years from now, history feeds will sum up the year 1995 solely with this image:

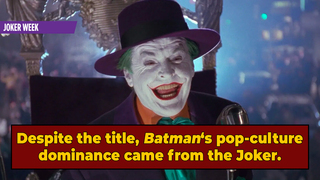

But we're getting way ahead of ourselves (and way, way off-topic). The worldwide dominance of Batman all started with Tim Burton's, well, Batman, a movie that despite the title ultimately belonged to The Joker. While Burton's Bruce Wayne was presented as a furtive, somber nerd, Jack Nicholson got free rein to gleefully chomp away at Anton Furst's Academy Award-winning scenery.

Don't Miss

Batman is already a full-fledged vigilante at the start of the movie, meaning that the bulk of the story's momentum comes from chronicling Joker's origin. Perhaps the filmmakers, so intent on distancing themselves from the calculated goofiness of the Adam West series, were less confidant in focusing on Batman himself -- which is ironic seeing as Nicholson's performance is pure hooting camp that makes his gonzo axe-wielding Shining mania seem subdued by comparison. Nicholson even got top-billing above the lesser-known (and needlessly controversial pick) Michael Keaton.

Perhaps the best explanation for the film's counterbalanced fascination with Joker though (in addition to Nicholson's fame) is Tim Burton himself. Burton admitted that he had "never been a comic fan" before reading his favorite graphic novel; Alan Moore's controversial 1988 book The Killing Joke, which similarly sketches out a backstory for the Clown Prince of Crime. "It's the first comic I've ever loved," Burton said -- which is kind of odd considering it was only released after he had agreed to helm a multimillion dollar Batman movie. While Jack Napier, Nicholson's slick mobster, in no way resembles the unnamed comedian in The Killing Joke, much of his origin aligned with the book.

The movie's obsession with duality and the inner-lives of gloomy outcasts is boilerplate Burton, but Batman also plays like his own internal struggle made manifest. At that point in his career, Burton was still in his twenties and had only made two features; Pee Wee's Big Adventure and Beetlejuice, two modestly-budgeted bizzaro comedies. Conversely, Batman was a mainstream Hollywood superhero movie, produced by Barbra Streisand's former hairdresser. In that light, we can read Batman as very much a metaphorical tug-of-war between Burton the artist (Joker) and Burton the businessman (millionaire Bruce Wayne and his commercially viable alter-ego).

Joker as a frustrated artist is obviously a big part of The Killing Joke, and Burton's Batman makes that characteristic even more explicit. Joker claims he's "the world's first fully-functioning homicidal artist" and there's a prolonged sequence where Joker gives a gallery full of antique masterpieces a modern outsider artist makeover -- all while blasting Prince on a boombox, because it was still the '80s, dammit.

One of Joker's early schemes involves poisoning random products, which would have innumerable repercussions, but the movie focuses on how it wreaks havoc with the vanity and false beauty of show business types, as Gotham's news anchors become increasingly unsightly.

Joker represents the artist, and Batman the commercial. They battle each other, not just over Gotham City, but for the affections of Vicki Vale. Mid-way through the movie, Joker's elaborate schemes randomly take a backseat to his horniness when he becomes obsessed with Vicki who, pointedly is a photographer and could be seen as a stand-in for the medium of film itself. Vicki is similarly an artist in transition; a former fashion photographer who has branched out into serious journalism, garnering acclaim for photographs of a violent South American revolution. It's these more artistically-motivated (and violent) photos that Joker is drawn to, while he labels her more commercial work "crap."

Jack Nicholson was producer Michael Uslan's first choice, while other options included Willem Dafoe, Crispin Glover, David Bowie, and presumably every other lanky weirdo working in Hollywood. Nicholson's casting, however, underscores many of these themes. Batman helped usher in the blockbuster superhero film, following on the heels of the Superman franchise which spluttered to a halt just two years earlier thanks to the dumbest of Hollywood machinations. Batman's adversary in a perhaps inadvertent meta-commentary is played by an icon of the Hollywood New Wave; Nicholson launched his career with countercultural classics like Easy Rider and Five Easy Pieces. So we're, in essence, watching a keystone of Hollywood's artist-driven, adult-oriented studio system working against the character who will help lay the track for the modern comic book movie -- arguably its antithesis.

There is also a low-key political undercurrent to Nicholson's Joker that's easy to miss. For example, Joker isn't just poisoning people with his own inventions, we see in one brief shot that he's actually uncovered a top secret CIA nerve gas and is using the U.S. government's shady bioweapons program against its own people.

This isn't the only reference to a corrupt federal government; Vicki Vale's award-winning photographs are of the Corto Maltese revolution, a nod to DC's fictional South American nation. In Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns, the island is similarly undergoing a violent political upheaval until the Americans secretly dispatch Superman to intervene.

The Joker's plans in Batman are ultimately very loose (and as we mentioned, become about horniness for like 45 minutes). If there is a common theme to Joker's plans, it's less about gaining power than it is about destabilizing capitalism. He poisons random consumer goods, preventing people from engaging with the free market. And in the end he floods the city with counterfeit money, showering the citizens of Gotham with bogus currency from atop his parade float (again while blasting Prince). Then he gasses everybody, brutally punishing them for simply desiring material wealth.

Ironically, this character then became a marketing bonanza for the film. Yes, Batman himself was huge, but there were a staggering amount of Joker-themed products -- especially considering he was the film's villain and his whole story arc revolves around murdering the public. There were beach towels and T-shirts and whatever the hell a Joker-branded "electronic laughing ball" is. In the action figure line, Joker tooled around Gotham from behind the handlebars of the "Joker Cycle" that was in no way a thing seen in the movie.

When the film premiered, fans showed up en masse dressed, not as Batman, but as Joker -- which, admittedly, is a way cheaper costume to pull off.

And perhaps the best example of just how ginormous the Joker became that year was the 1989 Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade. Instead of bringing out the Caped Crusader to entertain the kids in the crowd, Joker showed up on a parade float, again throwing fake money into the crowd. But this time, instead of attempting mass murder, he sang a song and did a slew of celebrity impressions ... hard to say which was worse, to be honest.

This newfound popularity helped perpetuate the cultural dichotomy of Joker that still exists today; he is a homicidal clown who is embraced by families everywhere. Few genocidal madmen get their own Fisher Price playset, after all. At the very least, we can look to 1989's Batman as the movie that helped shape Joker's importance, even ubiquity, for the Batman films yet to come.

While future iterations would generally move away from the "gangster who fell into a tub of acid" model, Nicholson's Joker cemented him as a legit cinematic icon who would go on to provide the heavy lifting in the next cinematic Batman series as well. There's a reason the world doesn't wait with bated breath to hear who's playing Mr. Freeze next.

You (yes, you) should follow JM on Twitter! And check out the podcast Rewatchability.

Top Image: Warner Bros.