5 'Whoa' Scenes From Ancient Earth School Forgot To Teach

If we're discussing the weirdest time in history, we usually find ourselves bringing up such periods as "the sixth century" or "right bloody now." But recorded history is just a tiny sliver of the planet's real history. For a real shake-up, look at what the truly ancient Earth was like, back when ...

The Period Between Dinosaurs And Humans Was Dominated By Giant Hell Birds

It is often said that, given how life has existed on this planet continuously for over 3 billion years, you are fortunate to live during the comparatively short length of time in which Earth is home to Dolly Parton. If that's true, than you are even more fortunate not to have lived during the 60 million years in which Earth was home to giant birds with bones sticking out of their mouths.

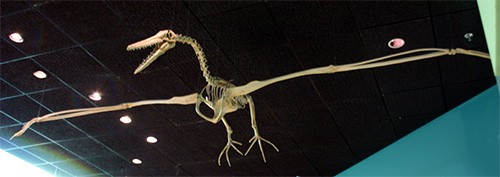

Note that we said "bones sticking out of their mouths" instead of simply "teeth." These were not teeth. They were outgrowths of the jawbone poking out of the bird's flesh, which is why this family of birds -- the Pelagornithidae -- are called bony-toothed birds, false-toothed birds, or nazgul-birds. The good news is that bones aren't as strong as teeth, so pseudotooth birds probably wouldn't sever your spine in two. They likely specialized in eating mushy fish or picking the brains of giant squids, so maybe they'd instead aim directly for your soft parts.

Pelagornithids evolved after those flying dinos known as Pteranodon had died out, and these birds managed to grow just as big as their lizardy counterparts, measuring some 20 feet across. With wings like that, they really never had to land if they didn't feel like it. They could glide for years, and go thousands of miles, without ever touching fully down, just dipping a bit to nibble on someone's head then using thermal currents to soar back up. Below, see an artist's depiction of one adorable specimen. According to the artist, albatrosses are "harassing" the defenseless, much larger fanged beast, while penguins "frolic" in the background because penguins.

Paleontologists found all their Pelagornithid fossils in Antarctica. The continent was a very different place during the reign of the Pelagornithidae, home to frogs and sloths and anteaters who sunbathed on the warm Antarctic beaches. It took the arrival of an ice age to wipe the Pelagornithids out. Does that mean that a warming planet will cause dormant dragon birds to break out of the Antarctic frost and reclaim the skies? We can only hope.

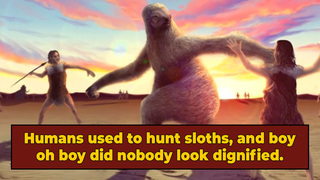

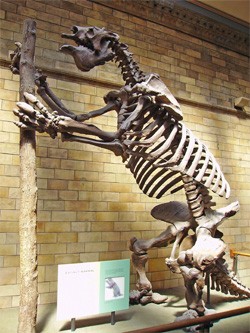

Humans Used To Hunt Sloths And Boy Oh Boy Did Nobody Look Dignified

Those sloths we mentioned grew a whole lot bigger as the millennia went by, especially when there were no stormbirds diving in and stealing all their Ritz crackers. In time, they evolved into the great sloth, a beast every bit as tall as the Pelagornithid was wide but which probably couldn't fly, because it weighted 4 tons. In the below photo of one complete skeleton of Megatherium americanum, we don't even need to include a gawking museum visitor for scale. You call tell from just the camera angle how huge this thing was.

And did early humans cower in fear from this monstrous herbivore? No! Early humans feared nothing. We hunted monstrous herbivores, and that's how we got enough raw material and energy to grow our giant brains and quivering pectorals. A fine example of what such a hunt looked like came in 1981, when geologists uncovered a bunch of sloth tracks in New Mexico. They promptly did nothing with their discovery, but then a couple years ago, paleontologists looked closer and realized there were human tracks inside the larger sloth ones. This meant humans were stalking the sloths by following in their footsteps.

The layered prints looked like a "Klingon Bird-of-Prey in negative relief" according to National Parks Service paleontologist Vince Santucci. Which is a little distressing to hear because we're the ones who are supposed to be describing things using unhelpful pop-culture comparisons. Then, when the team realized the smaller marks were human prints, they all responded with "quite a lot of profane language," says Santucci, further proving they're all gunning for jobs as internet comedy writers.

The team got a 3-D artist to mock up what this hunt must have looked like:

The sloth walking on his hind legs seems like the most obviously wrong part of this -- nothing that weighs as much as an elephant should be able to prance on two legs -- but the fossil record backs it up. We don't know if the fossil record also backs up his head turning almost 180 though his feet stay pointed forward, furry arms waggling as emptily as an inflatable tube man, while Pepto-Bismol clouds like comic book lines show the sloth's startled confusion ... but we aren't paleonstothogists, so who are we to judge.

Those Millions Of Years When We Suffered From Wood Pollution

Biodegradable materials break down thanks to living creatures. Bacteria and enzymes and stuff can chop up the bonds that keep the material together. If you try to think out how this cycle started, however, you run into a sort of chicken-and-egg situation. Trees die, and they decay, sure. But when the first trees died, how would any microbes have already evolved to eat them?

Just like the chicken-and-egg question (the egg came first, obviously), this paradox absolutely has an answer. When plants first started producing wood, there did not yet exist microbes that could break it all down. So trees would grow and die, and the wood simply accumulated. Maybe a fortunate spark would set off an occasional fire and get rid of some of the wood that way, but you couldn't count on that. And even if a brave animal tried nibbling on the wood, they'd poop out the indigestible base material ("lignin"), which would remain as intact as ever. This period of rampant wood pollution lasted 40 million years.

Over time, some wood piles would nab just right the conditions to turn into coal, which saved some space but did nothing to address the real problem: Plants were sucking precious carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, and no one was sending it back. This caused global cooling, and though that kind of improved things for the first few million years, it soon threatened to go too far. And if the carbon sinking continued forever, plants would convert all the carbon from the air into solid wood, leaving nothing left for them to make into food. All plants would die, and all animals would die soon after. (We'd compare this to some dead planet from Star Trek, but Vince Santucci ruined that for us.)

But things generally don't continue on the same path forever. And so, around 290 million years ago, mutations left a few fungi able to feed on wood, and that proved a very useful trait in a world drowning in the stuff. These mushrooms and their new "white rot" technique saved the world. The shrooms then evolved into termites, which evolved into beavers, which evolved into lumberjacks, and soon, Earth had a new king.

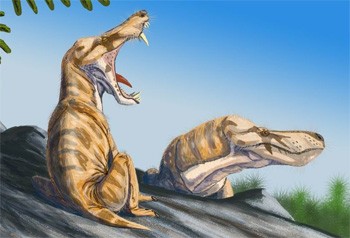

The Evolutionary Era Between Reptiles And Early Mammals Was Dominated By Hilarious Looking SOBs

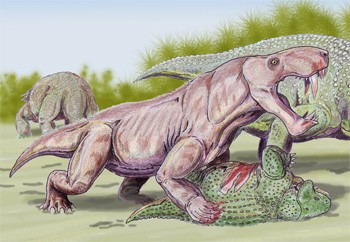

A couple hundred million years ago, the committee in charge of designing Earth's wildlife was having some problems. They knew that, ultimately, they wanted the planet to be ruled by organisms with breasts and chest hair, for obvious reasons. But the path of evolution leading up to that target wasn't so smooth. And so, they found themselves churning out therapsids, proto-mammals that still needed a lot of work. For example, you had your Moschops capensis:

Moschops hadn't quite figured out that your neck can be smaller than your shoulders, and it sank most of its evolutionary points into growing a thick skull. Scientists theorize that males engaged in combat by butting heads, which also explains why they adopted physique of a sumo wrestler. Also having some trouble with the concept of necks was Otsheria netsvetaevi:

Its head measured just four inches, so it would make for a good, if unsettling, pet. Pristerognathus was a couple times larger in length:

Pristerognathus, found in South Africa, appears to have been a sort of furry alligator, a phrase that obviously has many readers swooning with lust. The following therapsid, Dolichuranus, may not have been too different from a rhino:

We don't know exactly why the artist chose to depict it wearing lipstick and nail polish, and perhaps the fewer questions we ask about that, the better. Next up, we have another therapsid who made it a point never to miss jaw day:

That's Inostrancevia alexandri. It's named after Aleksandr Inostrantsev, and we can think of no greater way to be memorialized than to lend your name to an angry pink shaved panthersaurus. And of course no roundup of therapsids would be complete without a look at Myosaurus:

Myosaurus was so cute, it makes us seriously doubt the accuracy of any of these DeviantArt pieces masquerading as scientific reconstructions.

Go Back Further, And Each Day Was Just A Few Hours Long

In many ways, Earth's greatest enemy is the Moon. It is responsible for werewolf transformations, and for a while, the US seriously considered that the wisest course of action would be to attack it with nuclear weapons. Most insidious, though: The Moon steals energy from the Earth, perverting the nature of time itself.

The Moon constantly tugs on the Earth, you see, which is most observable through tides coming in and going out. This massive movement of the ocean across the sea floor creates friction, which works against the planet's rotation. On a day-to-day basis, this doesn't make any difference, but long-term, it slows Earth's rotation down.

So if we go back in time to dinosaur days, we see that the day wasn't 24 hours. It was just 23. We can determine this because even though the Earth 350 million years ago took just as long to go around the Sun (measured in seconds, or hours), a year used to be 20 days longer, based on signs we see in uber-ancient coral. So, each day lasted less time. If we measure even older rocks, we get an Earth 620 million years ago taking a full 400 days to go around the Sun, or maybe even more.

Go back to the start of plants, and a day lasted just 18 hours. Go all the way back to when that blasted Moon first came to be, and a day was just four hours. Mathematicians can probably draw accurate predictions from this to see how days will inevitably lengthen even more in the future, but as for us, we fear for the worst. Maybe the Moon will, against all logic, start pulling harder and suddenly grind the planet to an absolute halt. The day-night cycle will end, which will cause quite a few problems. Our calendars will have no way of moving forward. So it will be 2020 forever.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.