One Of America's Most Nightmarish Monsters Was A Nice Old Lady

Picture the scene: it's 1935 and you're a seven-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee. It's a sepia-toned summer day and you're playing outside with your favorite 1930s toy (a brick your teacher threw at you for not praying hard enough in school). Your mother is round back, scrubbing clothes in a big pan full of gasoline, as is the style. A chauffeur-driven black Cadillac pulls up and a grey-haired lady offers to take you for a ride. You've never been in a limousine before. A week later, you're in a different state being introduced to a couple who inform you that they're your parents now. You have a different name and a different birthday. You never see your mother again.

From 1924 all the way until 1950, terror stalked the streets of Memphis. Children vanished from porches and playgrounds. Babies were taken right from their cribs. Kids went to the hospital for a routine checkup and all that came back was a death certificate. The city had the highest infant mortality rate in the country, for no reason anyone seemed able to explain. In a horror movie, this would end with a band of plucky kids defeating a guy with a crow mask and a chainsaw for a hand. In reality, the mayhem was all the work of an eminently respectable society lady named Georgia Tann, who ran the Tennessee Children's Home Society.

Tann arrived in Memphis in 1924, fleeing a cloud of suspicion over adoptions in Mississippi. She was soon hired to run the Society, since 1920s background checks mostly consisted of making sure an applicant wasn't physically manacled to a dead prison guard. Over the next 25 years, Tann won widespread praise for her social work. Eleanor Roosevelt solicited her advice, while the mayor of Memphis was a close friend and political ally. She courted Hollywood stars and celebrities and did "more to popularize, commercialize and influence adoption in America than anyone before her," to the point that she's occasionally been dubbed "the mother of modern adoption," although mostly as a footnote to her more accurate title of "nightmarish serial killer."

Don't Miss

Behind the scenes, Tann's adoption work was completely motivated by personal gain. Before the 1920s, the standard practice for dealing with orphans was to cram them onto a train and auction them off to corn farmers along the route. Tann realized that there was a potentially lucrative market of childless couples in wealthier cities. When she took over the Children's Home Society, the average cost of an adoption in Tennessee was $7. Under Tann, that increased to $750, with all checks made payable to Georgia Tann personally. She spent the money maintaining her own luxurious lifestyle, because apparently nobody in the '40s was suspicious when their adoption agent screeched up in a limo offering a half-price on a baby if the cash came through before the bookies closed.

Between 1940 and 1949, Tann raked in at least $500,000, worth $5-10 million today. But even as she lived the high life with her profits, kids in her orphanage were routinely dying of malnutrition and medical neglect. Infants were shoved five or six to a cot, with no effort made to keep sick babies separate, so that deadly diseases regularly swept through the facility. To save money, staff didn't bother filling medical prescriptions or practicing proper sanitation. Babies who were unattractive prospects for adoption were starved to death, or simply left outside in the hot sun. Sexual abuse of older children was rife, with Tann herself alleged to be an enthusiastic participant. At least 500 children are believed to have died at her main care home, although the actual number may be higher, since many deaths were never even recorded. Most are believed to have been cremated or buried in unmarked mass graves somewhere on the property.

Meanwhile, Tann's money-making operations grew in leaps and bounds. Her travelling salespeople ferried dozens of babies out to California at a time, while newspaper ads offered older children for a fixed price, with a one-year no-questions-asked returns policy in case the kid had bad vibes or something. Children were given new names and backstories to appear more attractive to clients, who were happy to cough up an extra fee for the child of a handsome doctor who had tragically died in a car crash. Most of the adoptive parents were completely unaware that anything fishy was going on, believing that the hefty fees were needed to fund background checks and other paperwork. In reality, the only background check Tann ever did was "are these people rich enough to buy me another Cadillac, and maybe a new shovel for the care home." She was so successful that the demand for adoptions quickly outstripped the children placed in her home. So she just started kidnapping them instead.

In a little over two decades, Tann stole up to 5,000 children from around Tennessee. Doctors and nurses were bribed or intimidated into handing over newborns from maternity wards. The new mothers, often still sedated from giving birth, were told that their baby was being taken for tests, then bluntly informed that the child had died and been buried by the state. Tann targeted poor or unmarried mothers, who she contemptuously referred to as "breeders" and "cows," since they lacked the resources to protest or investigate. She used her position as a social worker to befriend young parents, offering to take their infant for a checkup. They never heard from her again, aside from a brief call to say the child had died. As time went on, Tann became bolder, cruising around in her limo luring children off porches. Blondes were particularly targeted because they fetched higher prices.

Tann was constantly on the lookout for new targets. If the local paper ran a story about a mother tragically dying, she would appear at the funeral asking about the children. A network of scouts identified potential targets, while Tann closely monitored welfare files for any vulnerable new mothers. She was particularly fond of targeting unwed women, who were commonly believed to be unfit parents, making it easy for Tann to have their children seized by the state and reassigned to her care. A word from the Care Home Society was enough for sheriff's deputies to storm into homes across Tennessee and remove the children. The lucky ones were adopted out. The unlucky ones never left the care home.

Many parents went to great lengths to regain their children, but they were systematically blocked by Tann, whose new wealth allowed her to bribe everyone from cops to politicians. She became an influential figure in Memphis and a close associate of the dominant Tennessee political boss E. H. Crump, who even changed state law to facilitate her adoptions. As Tann's social status increased, it became almost impossible for poor parents to challenge her, to the point that she could virtually take children at will. Barbara Raymond, who wrote the classic book on the scandal, described Tann as "very manipulative, and she could be very threatening. She could scare people with her power." It sounds like something from an insane Roald Dahl parody, but an entire American city was in thrall to an evil orphanage director and her army of crooked cops.

Tann's most important ally was juvenile court judge Camille Kelley, who wasn't actually a lawyer, having been appointed to the court largely on the basis of her work as founder of Memphis's first PTA. Kelley, the type of person who starts every sentence with "as a parent," was remarkably unsympathetic towards working women, insisting that "a mother in the home is of greater value to a child than money in the bank." Hopefully, it was also of greater value than food on the table and a roof on the house, since very few women in Great Depression-era Tennessee were working 18-hour days simply to throw more coins on their Scrooge McDuck money pile. Meanwhile, Judge Kelley herself was most likely taking bribes from Tann's child-stealing ring in exchange for turning hundreds of young children over to her care.

It's not like there weren't warning signs. In 1929, a fire broke out at Memphis's Industrial Settlement Home, which housed Black children removed from their families. Eight kids died, while the survivors "told bizarre tales of torture" and showed signs of starvation and severe beatings. A girl named Rosebud Ankton admitted to starting the fire in a desperate attempt to escape punishment, while doctors were shocked by the heavy scarring on several children. During the investigation, the administrator of the home was strongly defended by none other than Judge Kelley and Georgia Tann. The administrator was ultimately sentenced to 90 days light imprisonment. Rosebud Ankton got 15 years.

The cracks in Tann's empire started to show in 1941, when the national Child Welfare League publicly condemned the Tennessee Children's Home Society for "repeated failure to have homes of foster parents investigated prior to the placement of children for adoption" and "the unnecessary loss of life of many children which had been placed with it for adoption." Meanwhile, prominent Tennessee citizens had long been concerned about the child death rate in Memphis and the surrounding Shelby County, which was the highest in the entire nation. But Tann's power was so great that even a national organization saying "listen, this thing's a bloodbath" wasn't enough to slow her down. It was only in 1949, when Boss Crump's political machine was finally defeated, that the new governor ordered an investigation.

The results were immediate. The state pulled all support for Tann's organization after a shocking report found "on many occasions babies had been taken from their mothers at the hospitals when only a few hours old and placed in nursing homes in and about Memphis where they were without medical care. Many of these children died ... Not only that, but the children placed in the Memphis home itself were not properly cared for and many died while there as a direct result of violation of physician's orders." Newspapers that had previously carried Tann's advertisements now blared headlines like "State Probes Million-Dollar Baby Market," "Babies Carted Off At Midnight" and "State Investigator Says Force, Persuasion Used In Memphis Baby Racket."

At long last, it seemed like justice had come for Georgia Tann. And then she died. Just days after the report was published, and three days before the state planned to bring charges against her, Tann passed away from late-stage uterine cancer. Judge Kelley was forced to retire in disgrace, but maintained enough clout to avoid a jail term until she also died a few years later. In the end, nobody was ever prosecuted for the crimes. The evil monster hunting the town's children came with money and authority instead of a knife glove or clown makeup, and in the end there was no big satisfying punishment, everyone just died of old age. It probably counts as a comparatively happy ending, because at least Tann lived long enough to see her crimes exposed. Life's a mixed bag like that.

Tann's death allowed the scandal to be swept back under the carpet, but a wave of publicity in the '90s brought the story back to light and allowed hundreds of stolen children to reunite with their birth families. A typical story belonged to Alma Sipple, who was living in Memphis when she was surprised by a knock on the door of her one-room apartment. The visitor introduced herself as Georgia Tann and claimed to be in the building investigating reports of child abuse by a neighbor, although she seemed more interested in asking questions about Alma's own children. She eventually informed Alma that her daughter seemed sick and offered to take her to the hospital for a free checkup. When Alma visited the next day, she could see her daughter playing in her cot, but a nurse curtly informed her "You don't have a baby in there. Those babies belong to the Children's Home Society." Shortly afterward, she was informed that her child was dead.

Alma desperately tried to get more information, but was told only that Tann "has nothing to say to you." After spiraling into severe depression, she managed to pull her life together, but never forgot about the child. Almost forty years later, she was watching Unsolved Mysteries when Georgia Tann's face appeared and she "let out a scream. I said, 'That's the woman that took Irma!'" With the help of volunteer groups, she was able to reunite with her daughter, who had been raised quite happily with an adoptive couple in Cincinnati. Another victim of Tann's scheme described reuniting with a long-lost sibling, who whispered "I love you" as they embraced for the first time in decades. Survivors contributed to a book about their experiences. In 2015, a tombstone was raised over the mass grave of 19 of Tann's victims. It's a small memorial, but it's something.

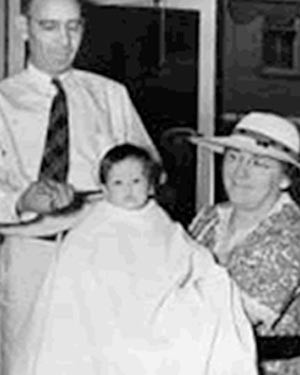

Top image: Luis Louro/Shutterstock, Wikimedia Commons