4 Notable Moments From History (That Got Overshadowed By Bigger Ones)

History, which is Latin for "stuff that's happened," covers a lot of stuff that's happened. Even professional historians only know a fraction of history, which is theorized to constitute over 47 different events. So much, in fact, has gone down that it's basically impossible to keep track of it all, which is why some of history's most fascinating moments went down while everyone was busy looking at something else important ...

The Other Olympic Black Power Salute

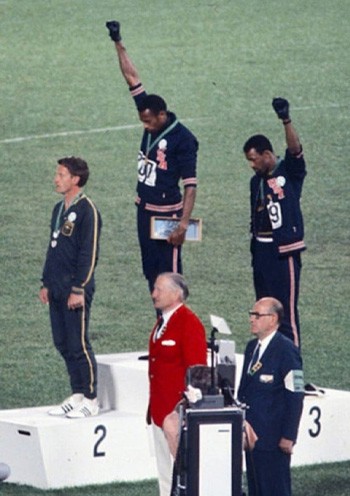

Even if you think Mario & Sonic at the Olympic Games is a realistic sports sim, you've probably seen this iconic photo from the 1968 Olympics.

In it, Americans Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who just won gold and bronze in the 200 meters, offer a Black power salute while Australian silver medalist Peter Norman stands in solidarity. 1968 was kind of a tense year for the civil rights movement, what with the whole MLK assassination, and a controversy ensued because it's considered in poor taste to politicize an event that Hitler once used to show off what a swell guy he was.

One very confused sportscaster (who's still active and unapologetic today!) called Smith and Carlos "Black stormtroopers," which was pretty much the high bar. There were death threats, while many white Americans presumably wrote to their newspapers about the "right" way to protest. If you want the full story, there are multiple documentaries, but the short version is that the trio later got a lot of apologies and statues (Australia was just as lousy to Norman).

There are no documentaries about Vincent Matthews and Wayne Collett, who won gold and silver in the 400 meters four years later. Their protest was a bit different -- during the American anthem, they just chatted, twirled their medals, and basically ignored the whole ceremony -- but their point was similar. As Collett would repeatedly explain, he loved America but wasn't going to respect the flag and anthem of a country that still created so many problems for its Black citizens.

There was another flood of outrage and debate. Matthews and Collett were dubbed disgraceful and childish, and it didn't help that the IOC immediately banned the pair, scuttling America's heavily favored 4x400 relay team. Whatever your opinion on anthems and sports, why has this remained obscure? Well, if you're up on either your history or your Spielberg filmography, you'll know that something else was about to go down at the 1972 Olympics.

Palestinian militants, blatantly disregarding the IOC's pleas to keep the Olympics apolitical, took Israeli athletes and coaches hostage. 17 fatalities later, and there was only one story everyone was talking about. The Munich massacre pushed Matthews and Collett into obscurity, and neither would compete again. Collett would earn a law degree and practice until his 2010 death, while Matthews has dabbled as an artist but otherwise dropped off the face of the Earth. But at least their work helped build a more enlightened America that would never again completely lose its shit over the way an athlete treated the national anthem.

The Serial Killer Who Made Headlines Before Jack The Ripper

We tend to think of serial killers as a modern phenomenon, if only because mass killers in the middle ages probably had a title and were targeting the right kind of heretic. Stories of famous medieval killers are so muddled that theories range from "They each killed hundreds of people" to "Maybe they were actually the victims of political conspiracies." It took a long time for stories of vanishing peasants to spread and form a coherent story back in the day.

That's why Jack the Ripper is infamous. By 1888, most people could read or at least trust their friends to not make up wacky fake stories when they asked what was in the news. And, by targeting a city instead of a sparse countryside full of disorganized subjects, there was a straightforward media narrative of victims, suspects, and concerned citizens trying to fight back. Except all of that was also true of Austin, TX's Servant Girl Annihilator, and Alan Moore didn't write a comic book about him.

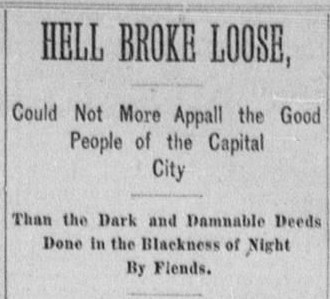

On December 30, 1884, Mollie Smith was found with several more ax wounds than the human body should have. Two more victims emerged in May, both brutalized with an ax or knife. All three had been Black women who worked as servants or cooks, so O. Henry gave the killer his name in an ironic letter that dubbed Austin an otherwise dull town. It was like if a Twitter user called a contemporary serial killer "the Big Stabby Boi," and it somehow stuck.

The name grew increasingly inappropriate as the victims expanded to include a little girl, two wealthy white women, and one man. The details are depressing, but the attacks culminated in two murders in different locations on Christmas Eve 1885. Then the Annihilator vanished.

At a time when "serial killer" hadn't even been coined yet and Austin's crack policework mainly revolved around beating random minorities, the eight murders gripped the city. Racial tensions spiked, the city's reputation was questioned by a flood of outside reporters, and sales of guns and newfangled burglar alarms spiked. Suggestions on stopping the killer ranged from blanketing the city with lights at night to, and this is serious, setting off the city's fire alarm when the next victim was found so that armed men could rush out of their houses en masse.

One possible perpetrator was Nathan Elgin, a 19-year-old cook who, in February 1886, assaulted a young woman and was shot to death. Another theory points to a Malaysian cook who worked near most of the victims and left for London in January, where his time in his new home coincided with the Ripper killings. But 400 arrests produced nothing substantial, and we'll probably never know the killer's identity.

Other, more outlandish theories also connect the Annihilator to the Ripper, who was equally brutal and captivating. But London's events entranced the world while Austin, with just shy of 15,000 people, was only beginning to shake its reputation as a backwater. Or maybe Jack the Ripper is better known just because he has a catchy, evocative name, while the Servant Girl Annihilator sounds like a straight-to-VHS b-movie made by some shlock director who later turned out to a sex offender.

The Failed Attempts To Fly Across The Atlantic

Charles Lindbergh: he flew the world's first nonstop solo transatlantic flight, his infant son was kidnapped and murdered in the Crime of the Century, and he has the always dubious "Attitudes toward race" section on his Wikipedia page. His Spirit of St. Louis is on permanent display at the National Air and Space Museum, in one of the prominent positions where you can't just sneak in and make airplane noises. But why, exactly, did Lindbergh fly 33.5 hours from New York City to Paris, beyond the fact that TV and video games hadn't been invented yet?

Well, there was $25,000 on the line, which is the modern equivalent of a cartoon KA-CHING noise. The only previous transatlantic flight had been between boring parts of Ireland and Newfoundland, and the Orteig Prize was intended to attract public interest in aviation and spur the development of new technology. In that, it succeeded. It also killed a bunch of people.

Hotelier and plane liking guy Raymond Orteig offered the prize in 1919, but it took until 1926 for the first serious attempt. Rene Fonck, one of France's most decorated war heroes, took off in a massive three-engine plane, but the overweight beast failed to get airborne, crashed down a gully, and burst into flame, killing two of his crew. In retrospect, they probably shouldn't have loaded up with ornate furniture, diplomatic gifts, and a goddamn multi-course dinner intended to be reheated and consumed upon landing.

In April 1927, a test flight captained by explorer Richard E. Byrd somersaulted and crashed upon landing, seriously injuring his co-pilot and flight engineer. 10 days later, two awesomely named American Navy airmen, Stanton Hall Wooster and Noel Guy Davis, suffered a fatal crash during their own test flight. In May, Charles Nungesser, another French war hero, went a step further by actually leaving Paris with eye-patched navigator Francois Coli. All seemed well when their plane, L'Oiseau Blanc, was seen heading over Ireland, but they were never heard from again. Lindbergh won the Prize two weeks later.

These were interesting men in their own right: Nungesser, for example, spent World War I accumulating dozens of medals, aerial victories, and newspaper articles about his drunken, horny partying. After a parade of concussions, bullet wounds, fractures, dislocations, and embedded shrapnel ended his military career, he took his aerial stunt skills to Hollywood and set endurance flight records over the Mediterranean. He's not well-known outside of France, but at least he was immortalized in the Young Indiana Jones Chronicles. No, seriously.

The Guy Who Sailed Across An Ocean For The Hell Of It

Humanity likes traversing things -- continents, oceans, planets -- and we've never let trivial details like "It's actually pretty easy to do that now" stop us from making it much, much harder than it needs to be. But making things harder than they needed to be was kind of John Fairfax's whole shtick.

Fairfax's life reads like a Daniel Defoe character was dropped into the modern world. He claims to have fled home to live in the Argentine jungle at 13, attempted a lovesick suicide by jaguar at 20 only to emerge with a new zeal for life, and spent three years as a pirate and smuggler based out of Panama, among other adventures. Admittedly, the source of all these claims is Fairfax himself, but he is on record as having sent a dead shark to a reporter who didn't believe he'd once fought one, so if nothing else, he was at least committed.

And what's undeniable is that on January 20, 1969, a 32-year-old Fairfax left the Canary Islands in a 22-foot rowboat stocked with oatmeal, Spam, water, and little else. His goal was to fulfill a childhood dream and become the first man to row solo across an ocean, although he would occasionally get a shower, a hot meal, and supplies from passing cargo ships. After 19 days, he'd only managed 83 nautical miles, and one of those ships offered him free passage back to civilization. He was sorely tempted but instead went back into the water and got to work on the remaining 3,500 miles.

The whole affair was so mind-numbing that Fairfax claims he talked to Venus for company, and his journal portrays the endeavor as a lonely and often miserable slog where the only highlights were helpful winds and the occasional fish dinner. By July 6, he was close enough to America that a plane full of reporters buzzed him to snap photos, but it still took him until July 19, half-a-year after he'd set out, to land in Florida. And then, the next day, man walked on the moon.

Fairfax's pretty neat achievement was overshadowed by a revolutionary one, although the Apollo 11 astronauts actually sent him a letter of congratulations upon their return to Earth. An exhausted Fairfax told reporters that the adventure had been so hard and boring that he would never do it again unless he had a woman with him. And so in 1971, he left San Francisco with Sylvia Cook, arriving in Australia 361 days later as the first people to row across that ocean.

Cook, discussing a trip where they battled a cyclone and had to patch up a shark bite on Fairfax's arm, said, "most of the time it's really boring." Fairfax died in 2012 after a long stint as a professional gambler, but at last report, Cook was doing well in a nursing home, where hopefully she blows people's minds on movie night by saying "Pfft, that's it?" to Moana.

Mark's Twitter account and new book have been unjustly overshadowed by history.

Top Image: Wikimedia Commons