Why Zombie Movies Will Have To Change Moving Forward

Zombies: they're the reason why we all think of Andrew Lincoln as Sheriff Rick Grimes and not just that creepy Christmas Eve stalker guy. But we can't help but wonder: where will the zombie genre go from here? And by "here" we mean the pristinely neglected Taco Bell restroom that is modern existence.

(And to those complaining that zombies are overplayed: we get it. But stories of the living dead date back to ancient folklore, and zombies just happen to be the dominant necromancy narrative of our time. To those parties we say, "It's a universal trope, jabronis.")

Don't Miss

In the early 2000s, some sort of biological agent became the de facto explanation for zombie outbreaks in movies, instead of just random acts of God or experimental agricultural equipment. So how will the zombie story shift now that we've experienced a real-life global pandemic first-hand? At the very least ...

Hollywood's Outbreak Narrative Has To Change

The immediacy of the zombie apocalypse might seem inauthentic now that we've seen that some governments will try to keep the economy for as long as humanly possible. In 28 Days Later, after less than a month London is completely shut down. If they were to make that movie today, the protagonist would probably stumble upon an operational Starbucks full of terrified employees.

In Shaun of the Dead, whenever Shaun suggests journeying to The Winchester pub amidst armageddon, his friends respond with utter bafflement. In retrospect, Shaun's passion for indoor dining and alcohol consumption even amidst a national emergency wasn't such a fringe viewpoint after all.

And if 2020 has taught us anything, it's that people increasingly don't believe actual scientific evidence; whether it's the anti-maskers or QAnon followers or the people who believe that the video of George Floyd's murder was a hoax presumably concocted by the Deep State branch of Industrial Light & Magic. We could easily see a zombie movie where some of the survivors don't even believe that zombies are a thing.

And it's not just wacko conspiracy theorists, a lot of Americans now distrust government institutions for not unreasonable reasons. Remember how a big part of the first season of The Walking Dead involved traveling to the CDC, only to find that it too has fallen to the Walkers? Today the CDC is currently under investigation for allowing itself to be influenced by political pressure from the White House; and famously, they published then pulled vital information about airborne coronavirus transmission. Given such historical precedent, it's hard to imagine the Walking Dead gang investing any amount of hope in the CDC. As for the news itself, it typically functions as a helpful source of information for characters.

But that trope, too, is difficult to wholeheartedly embrace now. What if our characters had stumbled upon a cable channel that, say, actively downplayed, and even denied the zombie outbreak? We can no longer watch movies about any virus without accepting the fact that misinformation, and the politicization of that misinformation, will be an integral part of the media landscape. They may even attempt to completely divert the zombie narrative, claiming the zombies are looters or rioters -- which is something we see playing out in the background of the South Korean blockbuster Train to Busan.

But while Train to Busan ticks a lot of these boxes, it is very much an allegory tailored for South Korean culture, aimed at a government that lied to its people about the spread of MERS and corporations that routinely devalue human life. Like the best zombie movies, the villains are not the zombies, but rather the rich businessman who, not unlike George Costanza, callously sacrifices others in order to protect himself.

But this too doesn't adequately address our times either. As an audience, we generally expect plot points to be informed by the barest causality -- think Chekhov's gun and like, well, every example of foreshadowing ever. But reality itself doesn't care about all those screenwriting do's and don'ts. No zombie movie ever ended with "the undead gradually overrun everything because of an incoherent combination of nepotism or creaky machismo or unhelpful grudges."

Can you imagine watching a film as narratively unsatisfying as that? It'd be like if the small-town heroes who band together at the climax to fight the undead horde get massacred because the National Guard ran out of gas. But that's not a movie, that's the sort of dumb stuff typical of the world we live in, which is, in turn, a Chief Wiggum gag. And as heartless as the villains of Train to Busan are, none of them are, say, arguing that doors aren't an effective prevention method against zombies. So really ...

We Need New Zombie Allegories

Moving forward, we're probably going to see zombies being used to different allegorical ends. This is nothing new, as zombies have served as stand-ins for everything from climate change to the paparazzi. For example, in his classic 1977 album Zombie, Afrobeat master Fela Kuti criticized the Nigerian military's draconian policies using both the zombie metaphor and so much delicious saxophone.

But in recent years, they have almost always come to represent the "other" to some degree. Of course, the master of the allegorical zombie movie was George Romero. While his seminal Night of the Living Dead has been interpreted as both anti-racist and a response to the Vietnam War, his follow-up Dawn of the Dead was an unsubtle loogie spat directly into the face of American consumerism Similarly, Day of the Dead is a "scathing parody of Cold War militarism."

And while it might not be an amazing movie, Romero's 2005 return to the zombie genre, Land of the Dead, might be the most relevant of the bunch today. Undeniably inspired by Iraq war-era America, Romero's fourth Dead movie focused, not on an outbreak, but on a society forced to live with the plague of zombies while the wealthy elites occupy a walled-off luxury community free from danger. And Romero again tackled race; the zombies not only aren't the villains of the movie, they're almost the heroes, a metaphorical melting pot of disenfranchised groups pointedly led by a Black man.

It's almost shocking how few zombie movies engage with the subject of racism seeing as the modern zombie evolved from 17th century myths that "mirrored the inhumanity" of the African slave trade in French-occupied Haiti. The same stories were later absorbed into the Voodoo religion, and popularized in America by William Seabrook's early 20th century travel book The Magic Island. Of course, Seabrook's encounters with zombies were likely just "slaves employed by American manufacturers, made to work 18-hour shifts and living in squalid conditions." Seabrook's writing paved the way for Hollywood movies such as 1932's White Zombie, about a wealthy plantation owner who enlists a Voodoo priest (literally named "Murder") to help him zombifiy a white woman he wants to marry. It's not great.

Even in the '90s Hollywood was giving us stories about white people returning from the grave thanks to Voodoo spells. Dead Men Don't Die, for example, starred Elliott Gould as a news anchor who gets murdered by a gang and is promptly turned into a zombie by the building's Black cleaning woman. Why? So she can move into his swank apartment. And lest we forget Weekend at Bernie's II which upped the original's corpse-based humor game by introducing the Voodoo Queen Mobu who reanimates Bernie, paving the way for an entire scene in which the deceased cokehead CEO goes conga dancing.

While zombie movies can be used to address any number of real-world issues, going forward we may get more of them engaging with the zombie's racial history, a trend we're already seeing. Just last year there was Zombi Child, a drama about a teen immigrant descended from Haitian zombies.

Furthermore, we expect more movies to actively sympathize with zombies. Our lives have become increasingly zombie-like, as anyone who's spent any part of the last seven months shuffling through empty streets in search of toilet paper knows. Which brings us to ...

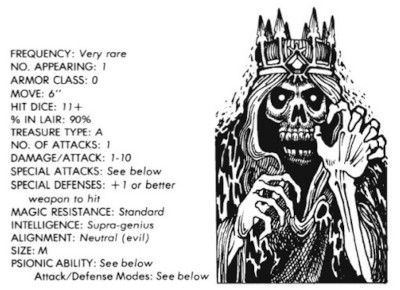

Riches are Liches

The mass horde analogy of zombies doesn't work right now because most Americans are suffering due to the incompetence/malice of a few. So if we're going to keep telling stories about the undead may we suggest ... liches?

Liches are also walking corpses, but unlike zombies, liches have the capacity for independent thought. If we're going to tell a zombie story, post-COVID, Liches are ripe for channelling our collective rage towards those who have actively profited off of the world's suffering. Liches already appear throughout pop-culture; from the stories of Conan the Barbarian creator Robert E. Howard to the Mountain Dew-stained pages of Dungeons and Dragons manuals.

Liches, sorcerers cheating death, are the perfect metaphor for the more corrupt politicians and business leaders who are exacerbating the current pandemic. And liches typically have the power of necromancy, meaning that they can still create familiar zombie armies -- but it's their foul actions that are responsible for the ensuing horror.

So yeah, it's lich season, Hollywood! That is, unless a certain space adventure franchise has totally ruined the concept of undead wizards ...

You (yes, you) should follow JM on Twitter! And check out the podcast Rewatchability

Top Image: Universal Pictures