Supreme Court Ruling Didn’t Fix Electoral College's Largest Problem: That It Exists

Putting new tires on a burning car isn't going to make the car better. It'll surely fix the problem of not being the proud owner of a rolling fireball that can explode at any second, but it doesn't address the deeper issues. That's basically what the Supreme Court has done with the Electoral College in yesterday's unanimous decision to let states sanction or straight-up remove members of the Electoral College who defy the will of the voters to vote for whoever they feel like, aka "Faithless Electors."

It's a nice ruling that fixes a long-lingering problem within the system. But maybe we should be focusing on how the Electoral College itself defies the will of the majority of voters? It's reducing presidential elections to a tabletop game, about 17th-century European farm management, that makes no sense, and while you were trying to figure out of the 40-page rule book, the winner won but they were actually the loser? Huh?

The Electoral College has given us five presidential candidates in U.S. history who won the hearts, minds, and, most importantly, votes of a majority of Americans, but they didn't win over the right people in the right places who count for more points than other people in other places (who are worth less), so therefore lost. Meanwhile, the loser, who convinced fewer people that they're fit for the job, goes on to rule a country that very loudly rejected them. The purpose of the Electoral College was to make sure the voice of smaller, lower populace states wasn't drowned out by bigger states. Or, at least, that was the idea.

If the issue at the heart of this Supreme Court case was about maintaining the core tenet of fairness, then maybe cutting out the extremely obvious middle man here so the total number of votes overall decides a winner is a more direct path toward representation? The whole issue of electoral representation and the question of who, exactly, is being represented (more importantly, who isn't) is thrown out of whack when you consider that one of the foundational purposes for the Electoral College was to give slave states more power. The Electoral College, meant to include more voices, was built on a foundation of exclusion.

The number of electoral votes is roughly proportional to a state's population. Tally the populations across the Southern states whose economies were dependent upon slave labor and suddenly you have a significantly smaller number of people compared to Northern states that weren't as dependent on slaves. The only way slave-owning states would agree to electoral reforms during the 1787 Constitutional Convention was if their state's votes were worth more as compensation for having a smaller population. Here's why that's trash: a lot of Southern states would have had enormous populations if they weren't so dead-set on being such diehard racists. James Madison was the Electoral College's fiercest proponent. He was a slave-owner from Virginia who fought for fairer electoral representation for his widdle, iddy-biddy state that was nothing but wind and tumbleweeds. But slaves made up 40% of Virginia's population. If they were actually counted as citizens, it would have made Virginia the most populous state.

Who knows, maybe if Virginia wasn't super into slavery and thinking black people weren't whole people, maybe Madison doesn't care about assigning smaller states more electoral power and the direct voting system proposed by Northerner James Wilson during that same Constitutional Convention would have become the law of the land.

Luis can be found on Twitter and Facebook. Catch him on the "In Broad Daylight" podcast with Cracked alums Adam Tod Brown and Ian Fortey! Check out his regular contributions to Macaulay Culkin's BunnyEars.com and his "Meditation Minute" segments on the Bunny Ears podcast. Listen to the first episode on Youtube!

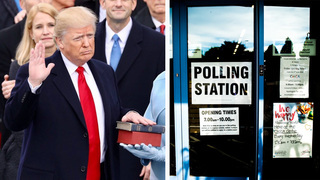

Top Image: The White House, Elliot Stallion/Unsplash