5 Crazy Stories From the War Between Coke And Pepsi

The rivalry between Coca-Cola and Pepsi, two drinks that are basically the same, is long-running and bizarre. The cola wars famously left Billy Joel unable to take it anymore, and this was a man previously unfazed by both the JFK assassination and hula hoops. The battle spans board rooms and classrooms, the airwaves, and outer space — and even the afterlife.

Mexican Villagers Were Convinced Coke And Pepsi Cleansed Their Souls

The native people of San Juan Chamula in Mexico had a long sacred tradition of drinking booze. That sounds like us just joking about how much they like partying, but we mean that literally — they brewed a drink called pox made by fermenting sugarcane, and men drank the stuff every day as part of a religious ceremony. The pox sacrament was a local practice with a bit of Catholicism mixed in, somewhat influenced by the Eucharist. The more pox you drink, they believed, the more you purify your soul.

Then the cola distributors came to town. Drinking cola is more sacred than drinking that yucky old pox, they said. Because cola leads to more burping, and when you burp after drinking cola, you release the evil from within yourself. Again, it sounds like we're mocking them, but this is what they were actually taught to believe. Some distributors said you had to drink Coca-Cola to get these benefits, while others said Pepsi. The Chiapas people chose sides and divided into sects accordingly.

Now, we all know that chugging sweetened black acid is bad for us, so are you thinking that subbing in soda for their beverage of choice turned the locals into obese amputees with meth mouth? The truth is a little more complicated. Soda is bad for you, but alcohol is worse, so Coke and Pepsi were set to actually free everyone from a lot of health problems. The only problem is, Coke and Pepsi are also a lot more expensive than pox. Each can of soda cost the drinker a day's wages. So people who bought the stuff, coerced by fears of damnation, had no money left for food, leading to massive malnutrition.

The drinkers believe in the Word of Coke genuinely, but there's corruption further up. Coke and Pepsi distributors make deals with the stores, receiving monopolies to cut out the other brand and demanding stores meet huge sales quotas. The caciques (chiefs) also get deals for distributing cola for free in exchange for backing political candidates. There may be hope, though. True, when the village of Mitziton protested against the corruption, thugs burned their houses down, but another village, Xoxocotla, rose up and kicked Coke and Pepsi out. (There's your elevator pitch, aspiring screenwriters.)

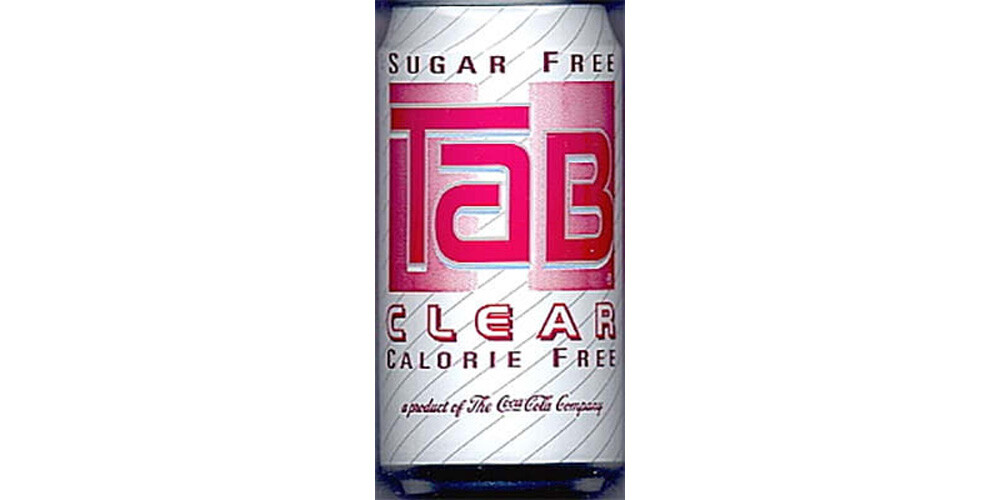

Coke's Terrible Diet Drink Sabotaged Pepsi

Okay, we started off a little heavy, but let's try to stick to lighter shenanigans from now on. Like that time in the early '90s, when Pepsi tried to revolutionize their product line with a variant that was caffeine-free and totally colorless. They called it Crystal Pepsi, and it actually sold very well. But it vanished, and its revivals were only middlingly successful.

Crystal Pepsi failed because Coca-Cola killed it. And Coke didn't kill it by so honest a tactic as releasing a competitor people liked better. Instead, in a deep betrayal of the moral basis of capitalism, they killed it by releasing a competitor they knew people would hate. They called their competing product Tab Clear, and rather than being caffeine-free, it was sugar-free. Marketing talked up what a medicinal beverage it was, and people equated it with Crystal Pepsi and came to believe that both were sugar-free drinks.

Today, that sounds like the sort of beverages consumers would like — Coke Zero and Pepsi Zero Sugar sell just fine. But the early '90s were a different era. Fat-free food was all the rage (thanks to secret lobbying by the sugar industry), but sugar-free food was considered a strange and tasteless type of plastic, only good for feeding to diabetics and plants. The soda-buying public avoided buying Tab Clear, and they also stopped buying Pepsi Clear. In five months, both drinks were dead.

This had been Coke's plan all along. Tab Clear was what marketers call a defensive product. It was never designed to succeed, just designed to protect Coke's overall market share. You can even price a defensive product so low that that you lose money on it — Coke never wanted to make money off Tab Clear, just to spread it widely till everyone started thinking, "Yecchh ... invisible cola" at every clear cola they saw. Meanwhile, their actual diet drink, Diet Coke ended up becoming the number two soda in the world after Coke, even beating regular Pepsi.

That Time A Kid Got Suspended For Wearing A Pepsi Shirt On Coke Day

You all remember Coke In Education Day as a kid right? You'd go to school, and for one special day, the entire curriculum would be switched around to teach you about Coca-Cola? You'd learn about the chemistry of Coke, and the business of Coke, and then you'd all go out on to the field dressed in Coke shirts to spell out the word "Coke"?

All right, maybe you don't remember it personally, but this was a thing that definitely happened. Coca-Cola invited schools around the country to participate, and they sent reps to schools to judge them on unknown criteria. They offered a $500 prize to the best school in each of several counties and a $10,000 prize to the best in the nation. It was a hell of a bargain for the company for such a ludicrous amount of direct kid-targeted advertising.

On March 18, 1998, Coke Day came to Greenbriar High School in Evans, Georgia. One senior, Mike Cameron, figured this was all kind of silly and came to school wearing a Pepsi shirt instead of the approved Coke one. It's a plot right out of Bob's Burgers or something, from the laughable premise of the school giving in to the branding promotion to the rebel kid's suspiciously perfect protest. What, did he just happen to have a Pepsi shirt sitting in his closet beforehand for no reason? (Yes. Yes he did.)

The school suspended him (which suited Mike, cool with getting a day off) for being rude and disruptive and potentially costing the school $10,000. That last claim had to be wishful thinking on the principal's part, since this one school stood only a tiny chance at the top prize, and anyway, it seems the Coke exec who saw Mike just laughed it off. Pepsi's response, meanwhile, was to call Mike "obviously a trendsetter with impeccable taste in clothes."

Right about now, the protest might seem kind of pointless to you after all. Ooh, you might be saying, you revolted by ... donning the logo of a DIFFERENT giant corporation! What a mad lad! But try searching the web for any Coke In Education Day resources today, and you'll just find coverage of Mike's stunt, so looks like he really did bury that campaign forever.

Pepsi Spent $14 Million To (Unsuccessfully) Beat Coke In The Space Race

You ever hear the story about how the US spent millions to develop a pen that writes in space, and it was all for naught, since they learned cosmonauts just use a pencil? It's not true. Pencils are very dangerous in space, with all their flammable wood shavings and conductive graphite, so pens are essential — and a private company designed the pens for NASA, economically. For a real story of money burned for a useless space gimmick, you instead need to look at Coke and Pepsi each trying to make a zero-gravity soda can.

Now, the question of how to store drinks in general in zero-gravity is a very important one. You can't tilt back a glass in space and let the drink flow into your mouth. That's why astronauts use straws (air pressure works even without gravity), and they pump drinks into reusable bags as drinking vessels:

Capri-Sun uses space-age technology.

But the cola companies wanted spacemen drinking soda specifically, and they wanted the soda to come in a branded can. They aimed to create a can that would preserve the drink's carbonated state and prevent the contents from spraying on the nav computer and sending everyone straight to Jupiter. Coca-Cola designed such a can with a lever and a plunger. It had a development price tag of $250,000. Pepsi, not to be outdone, developed their own can for $14 million. Perhaps realizing news of how much they'd spent didn't help their campaign, they told the press this research would also be useful for other applications. They declined to name any of these very real applications.

If all this convinced NASA to use Pepsi exclusively, and then perhaps laser blast the Pepsi logo on the Moon, this would arguably have been well worth it. But it didn't. NASA never planned to endorse one brand, and if they settled on one can design, they always planned to drink both brands from it. And then when they took both cans to space in 1985, astronauts concluded that ... neither tasted good. No matter what container you make, there's still no gravity, so soda won't bubble in your mouth. It just turns into foam, so it's like drinking caramel shampoo.

So, even decades later, spacecraft still don't carry soda. They're waiting for artificial gravity, which Pepsi and/or Coke are surely working on this very second.

The Battle To Own The Most Popular Song In America

If you order a mixed drink, you're probably going to ask for Coke instead of Pepsi. It's "Rum and Coke" or "Jack and Coke," not "whiskey and Pepsi" (nor "yogurt, absinthe, licorice, and Pepsi"). Partly, this is just because Coca-Cola's more popular overall, but there's also a cultural reason going back decades. Like so many unexpected things, this preference dates back to World War II, when servicemen in bases were blasted almost constantly with a song called "Rum and Coca-Cola":

This song would also be huge among the San Juan Chamula Indians.

This song was originally a Calypso number about US servicemen luring local women into prostitution. The Andrews Sisters version above puts a more sanitized and Americanized spin on that. Listen to it now, and you might struggle to identify what accent they're trying for or wonder why they think those words rhyme when they clearly don't, but it sounded just fine to a 1940s audience. Except, of course, to the folks at Pepsi, who panicked as soon as they learned the song was coming stateside.

They didn't want a hit song to namedrop Coca-Cola, so they contacted Morey Amsterdam, who'd adapted/stolen the original and rewritten it into the Andrews Sisters cover. Pepsi offered to pay him to change the words to "Rum and Pepsi-Cola." Amsterdam did the responsible thing: He gave the matter some thought, then contacted Coke, asking for a counter offer. Coca-Cola paid him an undisclosed large sum, and in exchange, all had to do was absolutely nothing.

Because the song so blatantly mentioned a brand name, radio stations refused to play it, and trade publications refused to track it. They considered it an ad (and, considering the Coke payout, they were right). They later partially relented and agreed to play an instrumental version, and DJs would refer to it only as "Rum and C.C." Somehow, that did nothing to stop The Andrews Sisters' vocal version from becoming a hit. We already told you how it was totally inescapable on military bases worldwide, and it in fact ended up the second-bestselling song of the decade.

That means in terms of sales, "Rum and Coca-Cola" was second only to "White Christmas" — and "White Christmas," even today, happens to be the bestselling song of all time. ("White Christmas," of course, was also a stealth ad for coke, in that it was secretly sponsored by the Medellin Cartel.)

When A Coke Spy Defected To Pepsi, Pepsi ... Turned Her Over To Coke

Coca-Cola famously keeps its recipe a secret, the sort of secret that leaves you wondering, "Wait, how can they do that? Don't they have to list all their ingredients, by law?" Ah, but take a look at a Coke label, and after the various types of sugar, you'll see the remaining trace contents summarized as "natural flavorings." That could mean anything. It could be cinnamon. It could be lemon peel. It could be possum sweat. Yeah, it's probably possum sweat.

We kid. There's probably some government rep who stops at the Coke factory to make sure they aren't grinding up rat hairs, and amateur chemists who've had a go at deconstructing the beverage have been able to do so pretty well. The story of the secret is more PR than anything. That giant vault in Coke headquarters that supposedly secures the only copy of the recipe is in all likelihood just a filing room with a fancy door. NPR is even pretty sure they uncovered a copy of the recipe one time, and no one cared.

But the mystique around the recipe was big enough that in 2006, a Coke employee figured Pepsi would pay big for it. Ibrahim Dimson approached Pepsi, using the sexy pseudonym "Dirk," claiming to have confidential documents about the manufacture process. Meanwhile, mastermind Joya Williams smuggled out a sample for a new product from Coke HQ to hand over to Pepsi. Their ultimate plan was to give all they had and more to Pepsi for $1.5 million. Pepsi considered the offer and then promptly contacted Coke to inform them of the plot.

The FBI set up a sting, sending an agent to pose as a Pepsi exec named "Jerry" and hand piles of money in a Girl Scout cookie box to the spies. Then once Williams and Dimson agreed to exchange even more contraband for even more money, Jerry revealed the truth and pulled out the handcuffs. Pepsi earned praise for doing the right thing and respecting Coke's trade secret. But really, even if they had Coke's recipe, what would they do with it? The cola wars are all about marketing, not changing how their product tastes. If we cared about taste, we'd stop drinking Coke and Pepsi, and we'd all switch to mango juice.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for other stuff no one should see.

Top Image: AlexAntropov86/Pixabay