Pro-Sports Forgot What Happened During The Last 'Pandemic Championship'

In early March 2020, NBA star Rudy Gobert tested positive for Coronavirus seconds before a game was about to start, resulting in the NBA suspending its season indefinitely. Other sports soon followed suit: the NCAA canceled March Madness; the NHL suspended its season; the MLB postponed opening day. League executives have spent the ensuing -- what day is it? Really? -- three months discussing various ways to have sports again, with proposals ranging from playing in empty stadiums to having the playoffs at Disney World to our suggestion: Zoom talent shows (Does anyone on the Orlando Magic know actual magic? Let's find out.). The sad reality, though, is that crowning 2020 champions may be impossible.

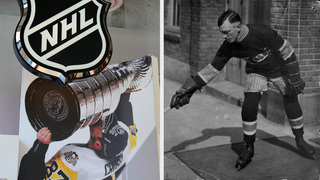

All of this is a huge bummer for sports fans, but it's not without precedent. Thanks to the influenza outbreak in 1919, we have an example of the time when a virus killed a sports championship. In the midst of the Stanley Cup Finals -- "midst," meaning one more game would've decided the championship -- a whopping 10 out 13 players from the Montreal Canadiens were too sick to play.

It had been a real rock fight for hockey's biggest and most-kissed chalice. The Canadiens and Seattle Metropolitans played five brutal games, including a double-overtime Game 4 and single-overtime Game 5. One newspaper described the teams as "pretty well used up," because zombies hadn't become a pop-culture reference point yet. Even worse, the rules back then meant Finals games, like Game 4, could end in a tie. So, all of that extra time in Game 4 spent zipping around an icy rink, pounding each other against boards, whacking each other with sticks, and knocking each other's teeth out didn't even bring them closer to winning. Injuries were rampant all series, leaving the teams so shorthanded that some of the guys who could play had to be carried off the ice due to exhaustion.

Game 5 tied-up the series, making Game 6 win-or-go-home (provided the didn't have another tie). That's when the virus hit. Hours before the puck was set to drop, several players developed 100-degree fevers. Some were bedridden. Canadiens manager George Kennedy offered to forfeit, but Seattle manager Pete Muldoon thought winning the Cup by forfeit was bullshit. Someone suggested borrowing players from other teams. League president Frank Patrick, presumably gesturing wildly at a series of hospital beds with groaning patients, nixed the idea of bringing replacement guys into the middle of an outbreak.

The end result was the deciding game being canceled and no Cup awarded. Multiple players spent weeks in the hospital. Canadiens player Joe Hall died less than a week after the games. Kennedy was permanently weakened by the flu and died only two years later. The Cup itself, which is engraved with the name of the year's champion, forever reads "no decision" in the 1919 slot.

In hindsight, playing out the series was extremely ill-advised. Influenza had shown up in Washington a year earlier, in 1918, and killed nearly 1,500 people in Seattle alone. Granted, the science for understanding and fighting viruses was barely past the "put a bunch of leeches on so they can suck out the sickness" stage. The virus itself was even lost to history when the pandemic died down, and decades passed before scientists had the ability to sequence it in a lab. It also didn't help matters that the severity of cases in the United States was downplayed by the media, thanks to press censorship meant to keep morale high during World War I -- even though the flu was far deadlier than World War I.

So why play the series? Well, you have to imagine life in 1919. America is still mostly a bunch of dirt-poor farmers and factory workers. Only a generation ago, smaller-scale disease outbreaks were relatively commonplace. And it's important to remember that professional sports were very new. This was back when cigar-chomping guys who happened to own a meat-packing factory could field a team made up of their workers, and everyone shrugged, grabbed some peanuts, and said, "sure; we'll watch this." Seattle's team was owned by the sons of the guy who invented numbers on jerseys. There was pride on the line. Not crowning a champion would be a blow to professional hockey's credibility.

Today, pro sports are different. The North American "Big Four" -- NFL, NBA, MLB, and NHL-- all have established histories and legacies built over generations of playing a yearly season and crowning a champion at the end. Playing most of a season and then not figuring out who was the best that year is essentially edging for a whole community of athletes, fans, and sports media. Plus, all these leagues are multi-billion-dollar businesses. Grown men playing games has a real effect on local economies. The person pressing record on the TV camera, the stadium vendor yelling about peanuts and cracker jacks, the bar owner down the street who also sells bootlegged T-shirts and hats--they all depend on games happening, too.

That said, at the end of the day, the games are just that: games. It's not so important that it's worth risking players' and coaches' lives and dragging healthcare professionals away from hospitals so they can check on some goalie's sprained knee. Health comes before the economy, and we definitely don't want any more Joe Halls and George Kennedys, right? Ah shit.

Top image: Leonard Zhukovsky/Shutterstock, Hockey Hall Of Fame