Whaa? Responses To New Technology

When a new technology appears, we all immediately act like idiots. Or, we act perfectly reasonably, but our grandchildren will be convinced we were total idiots. Even if they understand the strange primitive tech we use today, they'll be baffled by the exactly how we chose to use it. Just consider how it feels for us today to look back at how ...

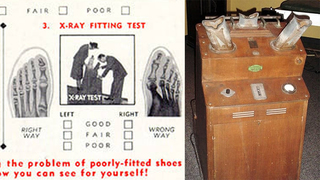

Stores Took X-Rays To Show Off How Well Your Shoes Fit

We first figured out how to use X-rays to take pictures of spooky skeletons back at the end of the 19th century. Then when World War I came around, medics in the field used X-ray machines to look at a seemingly endless number of potentially broken soldier bones. The rays that passed through skin and muscle proved equally capable of passing through leather. Doctors would X-ray men's feet right through the boots, since there were way too many bones queued up for examination to waste time with such formalities as footwear removal.

After the war, with no more injured patients lining up by the thousands, no one ever again needed to take X-rays right through shoes. But they went on doing it anyway. Because people figured that taking X-rays through shoes was really, really cool.

The foot X-ray machine was branded the "shoe-fitting fluoroscope" and soon appeared in department stores, with clerks urging customers to experiment with it and find what shoe fits best. Now, if you think about it for few seconds, you'll realize X-rays are a terrible way of determining whether a shoe fits. A scan can show you how much space the shoe leaves around your foot, but you can already tell that perfectly well just by putting the shoe on. Trying the shoe on actually gives you a much better idea of whether the shoe feels right, and you anyway have to try the shoe on to get the shoe X-ray. But, again, the X-rays were really cool, so they were a big hit among buyers of 1930s footwear.

Everyone wanted to size their feet using the proven power of SCIENCE! And it took a while longer for everyone to realize that radiation has its downsides and so generally isn't so well suited for retail therapy. We don't know that this infernal machine gave any customers cancer, but the possibility leaves historians worriedly stroking their beards. As for the employees who used the fluoroscope regularly, the risk was observably greater, sometimes leading to radiation burns and even leg amputation. States finally started regulating the machines and eventually banned them, saddening goth foot fetishists everywhere.

People Used To Listen To The Radio And TV Simultaneously, To Hear In Stereo

Passionate aficionados of the latest in audiovisual technology (aka weirdos) find themselves thwarted by a market that's consistently one step behind. Today, early adopters buy the very best in HDR screens then are furious to find that practically no networks broadcast anything in HDR color. A generation ago, we went through the same thing with HD video. You could buy an $8,000 HD television as early as 1998, but good luck back then finding much to watch on it.

Sound offers an even bigger struggle. If you decide to deck out your home entertainment system in 25-channel Dolby-Atmos-Jehovah-Earfellatio, you meticulously disguise dozens of speakers in strategic positions all around the room, and then you turn on a live broadcast that basically ignores all of that. Back in the mid-20th century, audiophiles had more modest demands but the same problem. They just wanted to listen to stereo sound (meaning two audio channels, with one sound coming from the left and a different sound coming from the right). But you couldn't get that over the airwaves.

Networks weren't going to take the plunge and figure out how to send a stereo signal because almost no one had the equipment to play multi-channel sound. And TV manufacturers weren't going to start installing stereo speakers without networks broadcasting in stereo, so they were locked in a Catch 22. Then The Lawrence Welk Show figured out a solution. Starting in 1958, they broadcast one audio channel along with the usual TV signal and sent the other out over radio. To listen to big band performances, you'd put your radio on one side of the room and the TV on the other then listen to both.

This gimmick continued for decades. By 1984, even dramas like Miami Vice were trying it. Radio stations weren't exactly big fans, however, of playing audio of action that was incomprehensible to anyone not watching the show at the same time, so they resisted the idea, no matter how many Tina Turner and ZZ Top songs Miami Vice squeezed in there. Eventually, stereo really did become standard, and everyone could dispense with all that rigmarole. And today of course, you can watch TV on your phone, with speakers that are so close together that you can't even tell it's stereo. Progress!

Early Computer Programmers Stored Code Using Rope

Computer code usually lives in microscopic bits of electronics, with tiny sectors assigned some value or another using magnetism. So long as you have to change code over and over, you need to store it in a format like that, so you can read and write at will using the power of tamed lightning. But if you only have to write it once -- if you're dealing with ROM rather than RAM -- you can store code in all kinds of different ways. You might know about the ancient art of punch cards, and today, we're going to tell you about another way to store code: rope.

Yes, in the 1960s, at a time when we had already figured out magnetic storage, programmers also wove code, like they lived in some fairy tale about a haunted tapestry or like they were from one of those ancient cultures who stored their language and math using knots. Wire rope wound back and forth, registering as a 1 or 0 depending on how it turned. You might wonder why anyone would store code using bulky rope instead of compact magnetic tape, but in the early days, rope was the least bulky solution. A cubic foot of rope could store 72 kilobytes. That's hugely bulky compared to, say, today's terabyte M2 drives the size of a stick of gum, but in those days, the alternative (magnetic tape) took 20 times more volume to store the same thing.

But why, you might ask next after thinking some more, did anyone actually even care about bulk? Computers were already taking up like whole buildings, right, so the quest for compactness was already a lost cause. When it was necessary, though, they really did have to make computers as small as possible. For example, when traveling to Mars. NASA's first probes to Mars used rope memory, as did the Apollo missions that followed. The rope was slow to manufacture and impossible to edit, so scientists had to finish their code long in advance of the mission and make sure it was absolutely perfect.

NASA's cord circuits were wound by women, which seemed appropriate to everyone involved because the job didn't look all that different from sewing or weaving. The female workforce led to a nickname for the storage system: Little Old Lady memory, or LOL memory. Now you know what it means when you crack a joke online and someone says "LOL." They're calling you a little old lady, because little old ladies are hilarious.

WebTV Was Originally Classified As A Military Weapon

If your television connects to the internet today, it's probably so you can stream video directly from a subscription service. You have plenty of other ways of accessing the internet of course, better ways, but a Smart TV throws the web on the largest screen you own. Back in 1996, however, when Microsoft debuted "WebTV," they had a different goal in mind. They just wanted to get people online at all. So for just $300, they'd give you a device that added email and web surfing to your TV while costing you less than a scary computer and a modem.

Was WebTV good? Not really. Many activities are more comfortable on your couch 10 feet from your screen rather than sitting at a desk, but browsing the early internet wasn't one of them. The below video, which looks like a comedy sketch mocking life in the '90s, shows a presenter struggling to use his remote control to load even a site he claims is well optimized for WebTV (it's the NBC page for Friends, of course). Yet somehow, WebTV -- later rebranded "MSN TV" -- kept on chugging along as late as 2014, long after cheap computers and phones should have made it obsolete.

WebTV used 128-bit encryption. That standard is so universal today that your browser will warn you if you ever try entering credit card information on a site that doesn't use 128-bit encryption. But in those days, it was revolutionary. And governments are not fans of revolutions. The US government at the time banned the export of any technologies that used encryption more powerful than 40-bit, figuring that anything stronger than that would inevitably be used by terrorists and criminal networks to keep their shenanigans secret. So they banned the export of WebTV, and they formally classified the set-top box as a military weapon.

Microsoft and other manufacturers estimated they were losing $30 billion by this designation. It took them a couple years of lobbying to get the government to change the law, a change that had to be approved by the FBI, the CIA, the NSA, Department of Defense, and four other agencies. So, Microsoft was eventually able to export WebTV worldwide. But just three years later, terrorists successfully flew planes into the World Trade Center. Coincidence?

For Years, CDs Were Only Popular Among Fans Of Classical Music

Compact discs are outdated now, replaced first by a series of digital file formats and then by "fuck it, we'll just stream our music. No one owns anything." Today, you probably associate CDs with the '90s, and you figure the radical format was used most for the most radical music of the time (rollerblading tunes, probably). But at first, CDs were only successful when it came to selling classical music, a genre that seems like it would have never clawed its way out of vinyl.

One reason: CDs cost a lot at first (plus the player itself cost $1,000), so mainly only older people could afford them, and older people were more likely to be classical fans. The other reason, though, concerned who most appreciated clearer sound. We're talking again about audiophiles -- which, we should clarify, is a word for people who like quality sound reproduction, and has absolutely nothing to do with the sexual practice of inserting a studio microphone into one's body. CDs were noted for recording sound with no distortion, and that best came through with crisp piano and violin, not buzzy pop songs.

The first standard CD ever manufactured was a symphony by Richard Strauss. The first pop CD manufactured was by ABBA, and it didn't really sell. Nor did any other pop CD -- pop fans stuck to cassettes. It took one mega album, the first to be recorded digitally, to really convert the public to CDs. And that album was ... 1985's Brothers in Arms from Dire Straits. Yeah, we don't know how much cultural relevance Brothers in Arms has today, or if you'd ever list it as the most transformative album of the decade that had Michael Jackson, Prince, and Madonna, but THAT was the album that changed everything for home audio.

Today, some people still swear cassettes sound better when it comes to pop, thinking the distortion smoothens the sound and adds warmth, just as other people are convinced vinyl beats everything. Thankfully, you can now capture the output from any of those perfectly and store it digitally. No matter what you think of new music being made today, you are living in the best time for listening to music ever. Let's leave you with this clip from 1982 unveiling the strange new compact disc technology:

"Compact disc may well rule the roost," says the presenter. "At least until someone perfects a method of putting Beethoven's 9th on a silicon chip. Don't laugh. I'm assured that that day, in fact, is not too far off."

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for other stuff no one should see.

Top image: Mikael Haggstrom/Wiki Commons