4 Famous Movie Cliches (And The Weird Reasons They Exist)

It's usually pretty easy to track where a popular storytelling trope came from. Say a screenwriter needs to make a character look like a badass who's seen some shit, so they give him an eye patch. Most people don't see an eye patch and assume "rampant pinkeye," no matter how likely that might be. So that gets the job done. Then other screenwriters see that movie, and they start associating "eye patch" with "seen some shit" because of it, so they put it in their scripts. Now an eye patch officially means "seen some shit" instead of "some shit where I see." That's how the process usually goes. But not always ...

Slipping On A Banana Peel Used To Be A Genuine Concern

From Looney Tunes to Mario Kart, the banana peel is a pratfall staple. Everyone knows the gag, but how did it become a joke in the first place? There's no way stray banana peels are that abundant, and what kind of assholes are throwing them on the ground anyway?

Well, back in the mid 19th century, everyone was that asshole. Bananas had become a new and popular street food, so imagine New York City, but with the hot dog vendors on every street corner hawking bananas instead. But while the 19th century's food game was on point, their sanitation regulations were less so. People would often just toss their trash into the street, which meant that New York became littered with banana peels. So while it's difficult to imagine anyone slipping on a single fresh peel in the middle of the sidewalk, imagine that there are hundreds of them, and they're all slimy because they've been rotting for weeks. Suddenly the bananaphobia makes sense.

Harper's Weekly lectured readers on the potential broken limbs that a discarded peel could create, and Sunday school teachers warned children that not only would their inappropriate disposal of a banana peel injure someone, but that injury could also put them in the poorhouse.

Bananas became a symbol of the wider urban trash problem, because their bright yellow peels stood out amidst piles of waste. The problem was eventually solved, as sanitation laws and organized garbage disposal efforts replaced throwing all of your shit away and letting wild pigs eat it up ( seriously). But by then, the banana peel pratfall had become a staple of vaudeville, and later silent films, and still later cartoons. And it's somehow survived to this day, which would be like cartoons a century from now making regular jokes about eating Tide pods.

The Haunted Indian Burial Ground Comes From A "Real" Haunting

"Indian burial ground." That's all you need to say, and the audience will instantly understand that the spirits of long-departed Native Americans are seeking righteous vengeance for all the cruelties inflicted on them, like genocide and being stereotyped as a culture of angry ghosts. The first person to think of this easy background story must have felt like a genius.

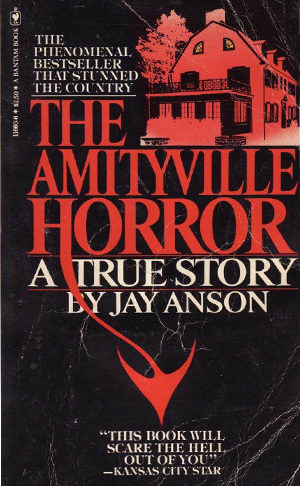

Unfortunately, that person wasn't making a movie; they were perpetrating a fraud. George and Kathleen Lutz bought a house in Amityville, Long Island, and they got it for cheap, in part because a young man named Ronald DeFeo Jr. had recently murdered his parents and four siblings in it, which kind of ruins the vibe at the housewarming party. But the Lutzes weren't afraid of no ghost, so they moved in, only to remember that they were indeed afraid of some ghosts. They soon experienced nightmares, hallucinations, inexplicable structural damage, strange sounds and smells, moving furniture, and other events that screamed "You're being haunted, idiots! Run!" The family found it harrowing, but luckily they were able to move out and parlay their experience into a book that sold ten million copies.

The Lutzes supposedly turned to the Amityville Historical Society to find out what the deal with all the haunting was, and discovered that the land the home was built on had been used by the Shinnecock Indians to pen up the sick and insane until they died. Furthermore, the dead were left unconsecrated because the Shinnecock believed the land was haunted by demons. So we've got brutal murders on top of an inhumane concentration camp on top of demons. Holy shit, it's like an evil lasagna! It's a miracle the Lutzes survived long enough to make tons of money!

But while the DeFeo murders were real, the rest of story wasn't. The Shinnecock stuff was especially easy to debunk. The tribe lived 50 miles away, there's zero evidence that they ever treated their own people with such cruelty, and the nearest human remains were found over a mile from the house. But hey, what's slandering an entire culture if it helps your book?

The book exploded into both a pop culture phenomenon and a host of lawsuits, none of which prevented the production of the 1979 movie The Amityville Horror. Between the hit book and the hit movie, the idea of a nefarious Indian burial ground became embedded in pop culture, spreading to Poltergeist II, The Shining,Pet Semetary, nine-freaking-teenAmityville movies, and several thousand other increasingly hacky horror stories.

Today it's more of a punchline than a serious attempt at horror, which we suppose is a fitting ending. Kinda sucks for Native Americans, though. But they've had it good for so long, what's one little knock?

The original 1740 fairy tale La belle et la bete, which was inspired by even older stories, was written in an age in which marriage was all about bettering a family's prospects. That meant it was routine for daughters to be shipped off to marry men they barely knew, and if they happened to end up loving each other, well, that was a nice bonus.

Seen through that lens, Beauty And The Beast's true message is less "Judge inner beauty, not looks," and more "Hey girl, your own interests and desires are completely irrelevant. You need to go marry what appears to be a uggo monster, but if you work hard, don't complain, and wife it up really well, you'll crack through his gruff exterior and find lasting happiness." A fairy tale was a socially acceptable way to soothe the nerves of young women and reassure them that their arranged marriage would work out fine once they got past the awkward monster stage.

Ironically, Beauty And The Beast's author, Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve, had an arranged marriage so terrible that it'd earn her a reality show today. She was stuck with a much older man who squandered most of their money, prompting her to attempt a legal separation. The man then died and left her impoverished, and she struggled to make it on her own until she shacked up with a playwright as his mistress. So she tried to ditch her shitty arranged marriage, then followed her heart despite the cost to others, which you may recognize as the exact opposite of her story's moral.

Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont, who abridged and popularized Villeneuve's story, didn't fare much better. Her first marriage was to a dude who picked up a venereal disease from his beloved orgies, and (in a rarity for the time) their union was annulled. Beaumont supported herself for a while before scoring a second, much better marriage. In what was presumably a zinger intended for her first husband, her retelling of the story emphasized the lesson that girls should value virtue over looks.

The Damsel Tied To A Train Track Comes FromQuick, picture a dastardly deed! Wait wait, don't tell us: You just imagined a guy with a top hat and a twisty mustache tying a woman to some train tracks, didn't you?

It is a classic. The damsel tied to train tracks trope first appeared in the 1867 play Under The Gaslight, in which the damsel was a man who was rescued by the leading lady. That started a train trend on stage, and later on film, where heroes and heroines would narrowly avoid all sorts of train-related mayhem, much like how countless modern action movies will feature an explosive plane or helicopter crash. But that exact scenario you pictured -- twirling mustaches, screaming damsels, approaching trains -- only ever happened in parodies.

The scenario is so cartoonish because it was born out of comedies. The two most influential examples are Barney Oldfield's Race For A Life and Teddy At The Throttle, both of which featured the mustachioed villain doing the nefarious damsel assaulting, and both of which were mocking the dramas of their time for their lack of subtlety. So the trope we all use today to mock simplistic, old-timey evil was in fact mocking even older-timey evil in the first place.

Mark ison Twitterand has a book.

Support Cracked's journalism with a visit to our Contribution Page. Please and thank you.

For more, check out 6 Weirdly Specific Tropes Movies Got Briefly Obsessed With and 6 Minor Movie Details That Always Mean One MAJOR Thing.

It would be pretty neat if you followed us on Facebook.