5 Hit Movies That Swiped Their Plots

Hollywood is notorious for remaking popular films in its never-ending quest for money. However, there are a finite number of stories that can possibly be told, and after a century of moviemaking, they're bound to start repeating themselves completely by accident. As we've previously discussed, this happens way more often than you'd think, in bizarrely unexpected ways.

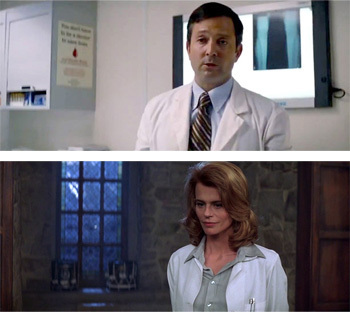

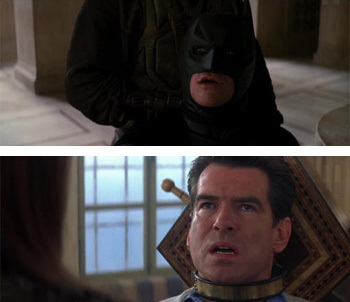

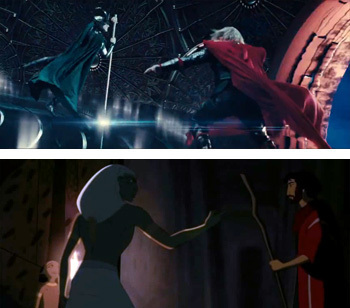

The Dark Knight Rises (2012) Is The World Is Not Enough (1999)

The 19th James Bond movie and the third Batman movie (or seventh, or ninth, depending on when you start counting) share more than the fact that they're both about handsome British actors grabbing people by the shoulders and shouting at them.

Sure, there's the obvious fact that both are about a suave, attractive action hero who owns an arsenal of expensive gadgets, likes to say his own name, and must overcome his physical limitations so that he can stop a terrorist kingpin from setting off a nuke in a major city, but that's lots of movies -- it's when you go scene by scene that you realize The Dark Knight Rises is The World Is Not Enough as told with rubber costumes.

Both films open with a prologue that features a midair action sequence in which the villain's henchmen willingly sacrifice themselves to rescue their master.

Then we cut to a scene where the hero's elderly British caretaker moodily reminds the hero that he's getting too old for the hero business.

After that, there's a scene in a poorly lit doctor's office wherein a doctor points at some X-rays to inform the hero that his body is falling apart after years of leaping off buildings and punching supervillains into submission, which triggers a somber midlife identity crisis.

The hero then meets a beautiful no-nonsense brunette businesswoman with a vaguely defined European accent. Nudity immediately commences.

But suddenly, another beautiful no-nonsense brunette woman appears. She doesn't serve any purpose to the story except to step in as the hero's replacement love interest after the other woman is disqualified from this position for reasons that will soon become clear.

Meanwhile, the villain from the opening action scene reappears -- a powerful, bald terrorist leader who talks funny and is impervious to pain. The hero is forced to once again don his hero shoes to deal with this destructive madman and pays a visit to his personal quartermaster, who describes to the audience all of the gadgets that will eventually be used in the film.

The hero pursues the villain to his secret underground lair for a one-on-one showdown -- Batman races around the streets of Gotham in a rocket-powered motorcycle, and Bond races around the streets of London in a rocket-powered ... um, boat. Jesus, that movie is stupid.

Anyway, the villain is able to exploit the hero's failing body in order to gain the upper hand, defeating the hero and stealing a nuclear bomb in the process.

Physically and morally crippled, the hero has to fight even harder to regain his strength and confront the bald terrorist again, only to discover that the bald terrorist is merely a hired goon working for the true villain -- the no-nonsense, vaguely European businesswoman he had sex with earlier! She subdues the hero and forces him to sit through a detailed monologue about how she plans to carry on her father's legacy, which somehow involves blanketing an entire city in a cloud of nuclear murder.

The hero miraculously escapes, there is another chase scene in which the bad guys crash and die in their own getaway vehicle, and the bomb is detonated safely out of harm's way. In the confusion, the hero absconds with the emergency replacement girlfriend who was clumsily introduced in the film's second act and retreats to a secret vacation spot to be spied on by his elderly British caretaker.

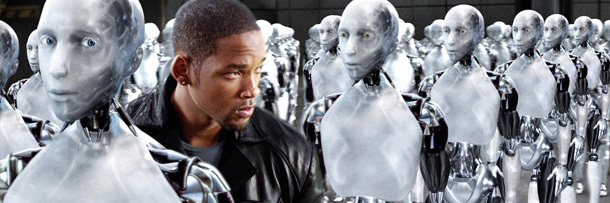

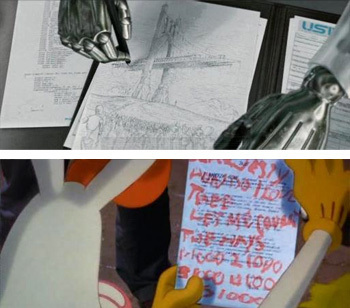

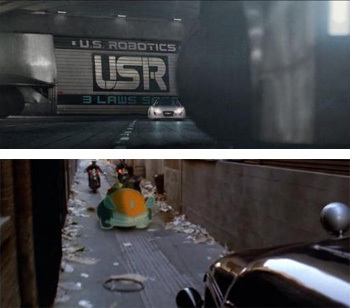

I, Robot (2004) Is Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988)

Even though I, Robot is an action/sci-fi Will Smith explosion-fest and Who Framed Roger Rabbit is a comedy starring popular cartoon characters from the past century, both are more or less the same movie if you use the words "robot" and "toon" interchangeably. One stars a wisecracking street-smart detective who is caught up in a murder mystery that thrusts him unwillingly into a world of cartoon characters and contemporary brand recognition. The other is Who Framed Roger Rabbit.

Both movies center on a cynical detective who harbors a deep-seated prejudice against a local community of sentient special effects because he blames them for a past tragedy in his life.

When a lovable member of this community is suspected of murdering a human being, the hard-boiled, disillusioned detective initially believes the toon/robot is guilty, because that's how racism works. He begins his investigation by interviewing a slimy CEO in a scene that involves him drinking liquor from a tiny cup while wearing a period-appropriate hat.

Then, at the insistence of an alluring female sidekick, the detective begrudgingly accepts that the toon/robot is innocent and agrees to solve the mystery. He learns that the victim left behind a note no one can understand (a cryptic dream hidden in the memory of a robot, and a mysterious "blank" piece of paper) that, we find out later, holds the key to a convoluted scheme:

The detective then quickly finds himself in a high-speed chase behind the wheel of a car that drives itself, a feature he considers extremely annoying rather than life-changing and incredible. The pursuit takes him directly into the heart of the community he so despises -- in Roger Rabbit, it's Toontown, whereas in I, Robot, it's future Detroit (where there is an astonishing lack of RoboCop).

Here, the detective finally cracks the case -- the real killer is a bombastically evil toon/robot who has been masquerading as a paragon of the human justice system in order to enact some diabolical scheme.

After defeating waves of henchmen, the hero dispatches the villain by exposing it to a magical substance that exists solely for the purpose of the villain's destruction, in an ending that curiously validates and reinforces the detective's bigotry -- the reviled community of metahumans was responsible for both his personal anguish and the murder at the center of the story all along. It just wasn't the specific lovable metahuman who was initially accused of the crime. So the moral of the story is, if you're harboring a deep sense of mistrust and resentment for an entire community, chances are your suspicions are absolutely correct.

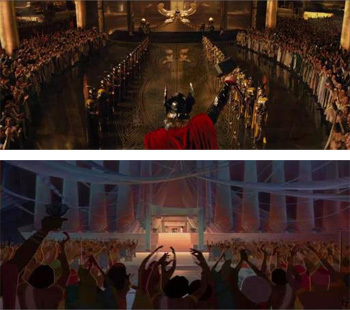

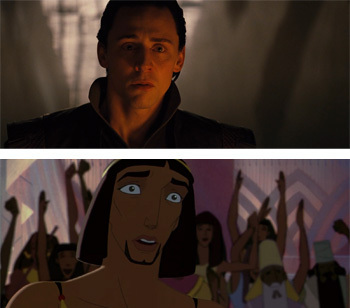

In a pop adaptation of a famous mythological story, the relationship between two princes becomes strained when their kingly father pits them against each other for his attention. After a monumental cock-up, the favored brother goes into exile among an alien culture, where he falls in love with a beautiful woman. Because fate is as cruel as it is predictable, he is eventually forced to protect his adopted people from the wrath of his heartbroken, embittered brother.

Clearly, that's the plot of Thor, but you might be surprised to learn that it is also the exact same story told in 1998's The Prince of Egypt (and, to a lesser degree, the Bible).

Both movies begin with a cataclysmic race war and quickly shift focus to two young, mischievous princes who enjoy recklessly goofing off in ways that cause violent, expensive damage to their father's kingdom. Nevertheless, one brother is clearly the king's favorite, and his jealous, more level-headed sibling constantly shoulders the blame for his brother's bullshit.

The two princes grow up, at which point one of the brothers discovers that he's actually adopted -- he was born to his father's cultural enemies, and the royal family took pity on him as a baby and raised him as their own, because for some reason no one foresaw that becoming a problem later on.

The hero (the favored brother) makes a hubris-laden mistake that gets him exiled from the kingdom. Outside the gates of his homeland, he meets a beautiful woman and a kindly old man. Through a series of fish-out-of-water hijinks, he learns to stop thinking like an inverted asshole and understand the plight of the common people.

Along the way, the hero takes possession of a blunt object that can do magic.

When he returns home, he learns that his father is dead/comatose, and in his absence, his less-favored brother has risen to the throne. Also, his brother has become a total shithead, driven by an irrational desire to prove his worth to a father who is no longer in any position to care.

The hero tries to reconcile with his brother, but only on the condition that his brother not murder all of his newfound friends. Unfortunately, his brother tells him to go jog down the street with that nonsense, and a kingdom-demolishing battle of wills ensues.

The hero is finally able to deliver a spirit-crushing haymaker that shatters his brother's resolve, and he gives up. Granted, in Thor it involves a shame speech from their newly awakened father, whereas in The Prince of Egypt it involves the wholesale murder of thousands of children. But the end result is the same -- the hero is free to protect his people, and his brother is forever a dick.

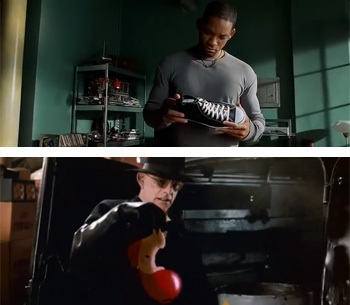

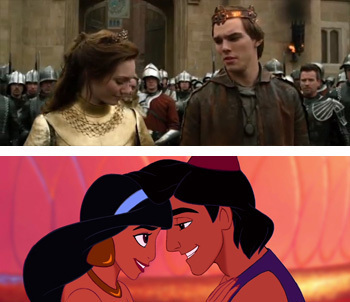

Jack the Giant Slayer (2013) Is Aladdin (1992)

Aladdin and Jack the Giant Slayer are both based on fairy tales, so you can assume right off the bat that some noble peasant has to go on a journey to save a kingdom from evil. But the similarities don't end there -- the movies are basically the same, give or take the presence of giants.

In both movies, a plucky young man living on the fringes of poverty ventures into the local marketplace to strugglingly procure something to eat, when he spots a beautiful woman dressed in rags being accosted by some slightly rapey older men. He stands up for her, even though he's drastically outnumbered, but before he is literally murdered in the street for his gallantry, the king's guards show up and reveal that the girl is actually the crown princess of the realm, disguising herself as a commoner to get a taste of how actual people live.

Soon afterward, the hero is given a magical relic that he is told holds infinite cosmic power, but he scoffs at the relic because it looks like a pile of old, useless crap -- in one film it's a rusty old lamp, and in the other it's a bag of shitty beans.

Meanwhile, the princess is commanded by her father to marry his evil bearded adviser, because that is the law of the realm (the fact that kings back then could ignore the law entirely and pretty much do whatever they wanted is never mentioned). Everyone seems to think the cartoonishly suspicious-looking adviser and his parrot sidekick are completely on the level, even though they spend most of their time skulking around the palace and scheming about a lost treasure.

The villain eventually learns that the destitute young hero is in possession of the magic relic and tries to drown him so he can steal it.

The drowning doesn't work, but the villainous adviser is able to use the relic anyway to get his hands on phenomenal magic powers, which he uses to bend the kingdom to his will. Paradoxically, his will in either case doesn't go beyond "tenuous command of an army of hateful giant ogres" and "making a fat old man dance in his underwear."

In the climax, the hero is forced to battle a giant evil monster, which he defeats by using the villain's own weapon against him. As a reward, the king removes the law that forbids his daughter from marrying a commoner, which he could have done in the first place, but apparently he prefers to just trade his daughter for services rendered in lieu of a paycheck.

The hero and the princess get married, even though they've known each other for all of two days, and they live happily ever after. Probably.

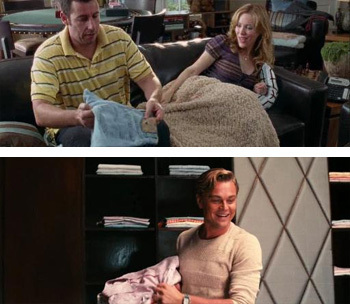

Funny People (2009) Is The Great Gatsby (2013)

Funny People sees Adam Sandler taking on the greatest acting challenge of his career as he portrays a once-funny comedian who has been reduced to making idiotic movies for truckloads of cash. The Great Gatsby has Leonardo DiCaprio playing a millionaire playboy who is dead inside and throws his money at people to make them like him. Both movies are ultimately about a rich, depressed eccentric heroically trying to have sex with a married woman and suffering tragic consequences.

At the beginning of both films, we're introduced to a reclusive millionaire who has a reputation for being the life of the party, but in reality is completely miserable. He befriends a good-natured nobody in a chance encounter, and the two become inseparable.

We learn that the millionaire's depression and profound douchebaggedness are both due to the fact that he's spent half of his life pining for an old girlfriend whom he has since lost touch with. Through the help of his new schlub best friend, he reconnects with her, only to discover that she's married to a guy who is even more of an asshole than he is.

Undaunted by this trivial detail, the hero seduces his former lover once again, partly by giving her clothing, and partly by being a millionaire.

She admits that she loves him more than her husband, which leads to a tense dinner confrontation in which the hero demands that she admit her true feelings in front of the whole cast, in a scene that seems to suggest that the hero is only slightly more rich than everyone else.

But she tearfully changes her mind at the last minute, causing the hero and her husband to have a weird anti-fight consisting of shouting and sweaty masculine posturing.

The girl ultimately decides to stay with her husband and work things out, while the hero is left with nothing but bundles of money to cry into. Of course, the big difference here is that The Great Gatsby surprises the viewer by unexpectedly killing Gatsby at the end, while Funny People surprises the viewer by unexpectedly not killing Adam Sandler (he spends the first half of the movie with a terminal illness, and then ... gets better). Both endings are tragic in their own right.