6 Old Products That Solved Problems We Forgot Existed

We take modern conveniences for granted. Today, you get people saying, “I wish these people praising A.I. would make an A.I. to do my laundry,” forgetting that we already did build a laundry robot, and before the washing machine, laundry consumed a whole day of the week.

Let’s keep in mind how revolutionary some products were when they first debuted. Luckily, we have a fine record on how they were originally sold to the public, thanks to the medium of advertising. Once upon a time, manufacturers unveiled their wares with such promises as...

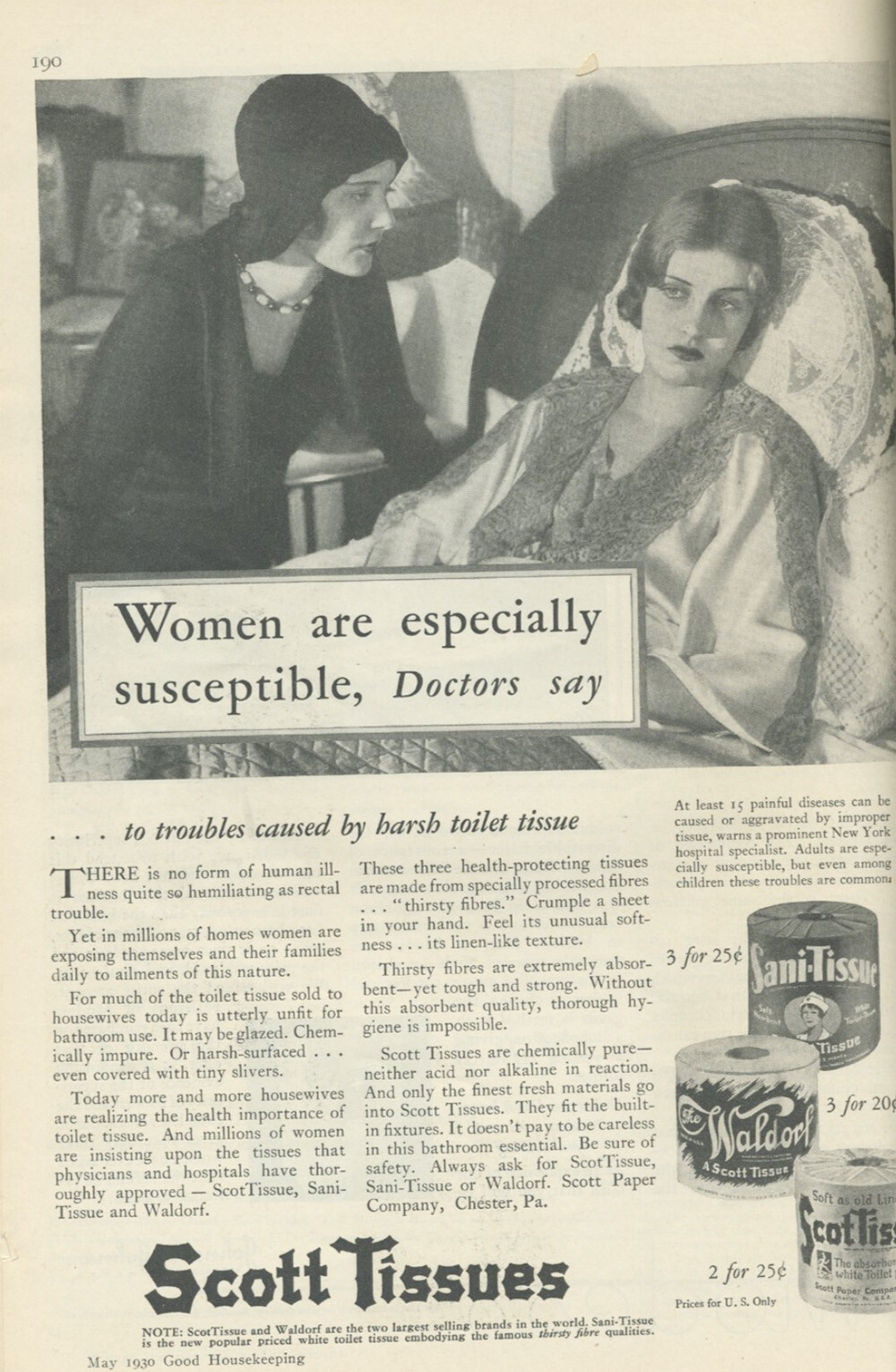

‘Tired of Splinters in Your Vagina? Buy PROCESSED Toilet Paper!’

Scott Paper Company

The very first commercial toilet paper was made of hemp soaked in aloe vera. That sounds pretty soft and comfy to us. It was a luxury product, however, and few were willing to pay a premium price for something so disposable. A more marketable version later came from the Scott Paper Company. That was the official name, by the way, of the company that made Scott-brand tissues and is unconnected to the Michael Scott Paper Company. Or, maybe The Office purposely named their character “Scott” to set up a “Scott Paper Company” joke; we don’t know.

Scott made toilet paper into rolls, which proved much more convenient than squares from a box. They also made their toilet paper out of wood pulp, the same stuff most paper is made of, which proved cheap enough for anyone to buy. But wood pulp has a problem: splinters. These can wreak havoc on your anus, or on other soft parts of your body, parts that ads couldn’t directly name but could allude to by describing this as a women’s problem.

A little processing, however, and toilet paper became soft enough to use without risking wounding yourself. Use Scott Tissue, said the above 1929 ad, for splinter-free wiping! It’s the best choice, short of wiping with silk, or short of wiping with someone’s wedding dress.

‘Got No Can Opener? Get a Can With One Built Right In!’

Alcoa

Today, when you buy a can of food, it might come with a tab you can pull to easily open it. Or, it might not, requiring you to use a separate can opener. If you’re opening some peaches in your kitchen, you probably have a can opener handy, but if you’re looking to eat some beans on the subway, you’ll find a tab-style can more convenient.

Originally, no cans had tabs. You always needed can openers (which were much more primitive and hard to use than today’s can openers, by the way). When the can held a beverage, you wouldn’t bother cutting away the entire top of the can but instead would puncture the top, just enough for liquid to pass through.

Finally, after decades of research, the 1950s brought us the pull tab. The above ad, which is from an aluminum company rather than a beermaker, demonstrated the convenience of this addition. It would take another couple decades for someone to invent the stay-on-tab. This variant, which we still use today, left the tab connected to the can even after you opened it. The earlier type, which remains in use in some parts of the world, left you with a separate piece of removable metal that you’d litter on the ground or would accidentally slice open your flesh.

‘Sick of Squinting at Your Radio? Try Automatic Tuning!’

Philco

The 1920s might have been the Golden Age of Radio, but it wasn’t a very convenient time for radio listeners. Tuning the radio meant tinkering with inductors and capacitors. As the above ad shows, it also meant peering close at something tiny and squatting to bring yourself down to the right level. Manufacturers needed to make radios more user-friendly.

The answer came at the end of the decade, with automatic tuning. That didn’t function very well at all and left radios drifting away from whatever frequency you chose. At the end of the next decade, Philco came out with their own automatic tuning system, and this one actually worked. It was called automatic frequency control, and it was a fine innovation that you personally have likely never used. That’s because, after another 30 years, it was replaced with something better called a frequency synthesizer. You use that today, if you listen to the radio, which you don’t.

‘Flies Keep Landing in Your Milk? Try a Thermos!’

Thermos

You think of a thermos as something you take with you. At home, you have a fridge, but a thermos keeps your drink cold or hot when you’re on the go or out climbing mountains. The vacuum flask (that’s the real name for this type of container) predates the home refrigerator, however. It began as a scientific instrument in 1892.

Starting in 1906, these flasks were marketed for home use by the Thermos company. That’s Thermos with a capital T, as this was a proper noun before the word became genericized. The above 1912 campaign advertised the device with the winning argument that it avoids killing babies. A Thermos kept your milk cold, which lengthened how long you could keep it before it spoiled. And if that was too complicated to understand, this sealed container kept flies from landing in your milk and dropping flecks of poop into it.

‘Map Doesn’t Show Enough States? Buy a New Atlas!’

National Geographic

Don’t you just hate it when the nation goes and adds a new state? Your old flag becomes obsolete (the law says you must now ceremoniously burn it), and so do all your maps. Fortunately National Geographic has an update for you. It’ll be the last atlas you ever need, at least until South Texas achieves independence.

Maps today are digital, free and update continually without your even noticing. This leaves the fine people at National Geographic free to turn their talents toward other matters, such as — wait, Walt Disney laid them all off, never mind.

‘Typing Takes Too Long? Buy Some Templates!’

Addressograph

This 1970 ad is a snapshot into a specific era. Companies had stationery that they ordered in bulk, as you can see from the return address professionally printed on this envelope. They didn’t yet have their own computer printers and had to add the recipient’s address with a typewriter. And what if you had to send mail to the same addresses often? Enter Addressograph, with plastic plates that could add that address repeatedly with zero chance for errors.

Addressograph began as a dedicated addressing machine in 1896, when typewriters weren’t yet a universal part of offices. The company got swallowed up by the start of the 1980s, not just because of the rise of computers but because of the rise of Xerox, which became the primary way offices duplicated text.

For a little while, though, they tried their best at adapting to the changing times with this pun-filled campaign, positioning themselves as better than the ladies in the typing pool. At least, we think “mis-directed” is a pun about that. Either that, or the hyphen is simply an error, the sort that a human stenographer should have caught.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.