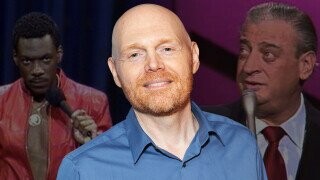

Bill Burr Wanted to Be More Eddie Murphy Than Rodney Dangerfield

When wanna-be comic BilI Burr was 18, he saw Rodney Dangerfield perform one-liners live. “A master comedian,” he says. Shortly after that, Burr caught Eddie Murphy, “another monster performer. Back to back, Rodney then Eddie.” Burr loved both comics, but he noticed something that stuck with him. At the Dangerfield show, everyone in the audience looked like Burr. “But looking at Eddie’s audience, I remember consciously thinking, ‘He’s making everybody laugh.’”

And that, Burr explained in Satiristas: Comedians, Contrarians, Raconteurs & Vulgarians became his goal, years before he ever got on a stand-up stage. “I knew I wanted to do what Eddie did: make everybody laugh,” Burr said back in 2009. “Of course, in this country, ‘everybody’ means Black people and white people — I wasn’t really thinking about Asians. I’m joking about that, but really, no one ever does think of Asians with the same sensitivity as Black/white stuff.”

Long before “white privilege” became part of the popular vernacular, Burr noticed significant differences in his audiences. “When I’m down South, I always ask, ‘Did you find Dukes of Hazzard offensive? A couple of rednecks driving an orange car through a barn, screaming, ‘Yee-haw’?’’ Where was the Redneck NAACP on that one? That was the Amos and Andy of white Southern culture,” he joked. But he understood why those kinds of jokes were considered fair game. “People never see redneck jokes as racist or offensive, because if you’re a white, heterosexual male in America, you couldn’t have been dealt a better hand, let’s be honest, so you get less sympathy, that’s all there is to it.”

Don't Miss

To become more Murphy than Dangerfield, Burr “started doing Black rooms and did BET and The Apollo for the same reason I love doing stand-up in cities where you get those mixed crowds: what you’re saying doesn’t get lost.”

Get lost? Hey Bill, give us an example of what you mean by that. “With an all-white crowd, the same joke can take on a whole different meaning, whether you want it to or not. Back in the day, I used to do a joke about kids acting like gangsta rappers. In New York, people were, ‘Oh yeah, I know guys like that. They’re hilarious,’” Burr said. “But in South Bend, Indiana, I go, ‘What’s up with these white kids acting like gangsta rappers?’ And this angry white guy in the back goes, ‘YEAH!!’”

Not exactly the response Burr was after: “I was, like, ‘Hey, easy, fella. I’m not going the Klan route with this, I’m just making fun of ’em.’”

Playing in front of different kinds of audiences helped Burr make sure crowds weren’t twisting his jokes to mean something he never intended. “But I find it interesting that people think we can’t openly discuss race or gender or any of that,” he explained. “It’s really not that big a deal. People say it’s ‘taboo’ or ‘edgy,’ but those walls were broken down long ago; people aren’t nearly as shocked as we think they are.”