Michael Keaton: The Batman Who Laughed

Welcome to ComedyNerd, Cracked's daily comedy superstore. For more ComedyNerd content, and ongoing coverage of that venerable 80s hilarity-that-turned-dark-knight, the Iran/Contra Affair, please sign up for the ComedyNerd newsletter below.

Don't Miss

Michael Keaton is another one of those Boomers who just won't retire. In the next few months, he’s got The Protege, a sexy thriller with Maggie Q, Netflix 9/11 flick Worth, and Dopesick, a Hulu series about opioid addiction. It’s all pretty heavy stuff -- except for a reprise of perhaps his most famous role.

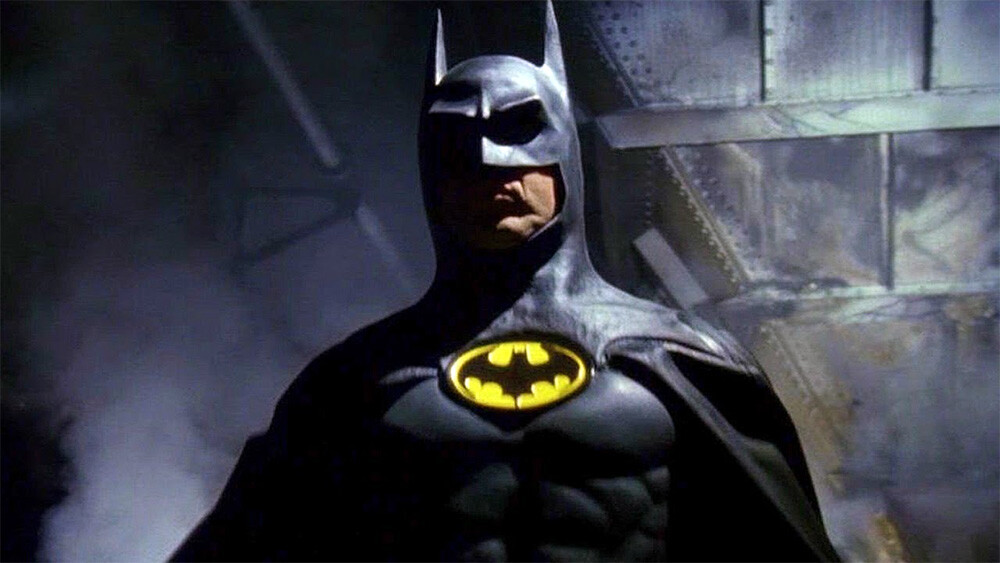

Warner Bros.

At nearly 70 years old, Keaton is returning as Batman (or at least, an alternate universe version of him) in the upcoming DC superhero movie The Flash.

"(It was) weirdly and ironically easy,” says Keaton of his Flash-back. “A little bit emotional. Just a rush of memories."

Most probably don't remember but Keaton was a controversial choice for Tim Burton’s Batman, and not just because he wasn’t the stereotypical action-hero type. You see, before he was Batman, Keaton spent a decade as one of America’s preeminent jokers.

The man who disappointed Cher

“I met him standing on line at Catch a Rising Star in 1974,” remembers Curb Your Enthusiasm’s Larry David. “Isn't that something? I saw him here and there doing stand-up.”

Keaton was about 22 years old when he moved to the coast to try his hand at stand-up comedy. Like many struggling actors, he held a series of odd jobs, working in restaurants, parking cars, taking a gig as a singing busboy. “I always just wanted to do everything,” he told Ellen Degeneres.

(Everything also included a gig at a public television station in his hometown of Pittsburgh, where he worked on the crew of Mr. Rogers. Rogers "was one of the nicest, authentically good people you've ever met," Keaton says. "Really good dude with kind of a sneaky, sly great sense of humor.")

Stand-up was a natural for Keaton. While his old comedy sets have a few detractors (Rolling Stone says he “wasn’t very good at it”), most agree that Keaton the comedian showed a lot of promise. His Bazooka Joe bit seen above, in particular, hasn’t aged a day -- it’s a routine Keason could easily deliver on a stage tonight and get a killer response.

What made him so good at it? “Some of these comics have a comic personality about them,” says his Dopesick director Barry Levinson. But Keaton “was just up there, talking. He had an ease, a natural quality.”

Michael Sugar, who produced Keaton’s Spotlight, agrees about the comic’s innate ability to entertain. “Conversations with Michael are like M.C. Escher paintings, where everything’s going in a million directions, but it all comes back to a cohesive image.”

The best indicator that people were buying Keaton’s comedy? He got work. For example, he was cast as part of the singing/dancing/comedy troupe for two versions of a failed Mary Tyler Moore variety show.

(Take note: This is very likely the first, last, and only time you will see David Letterman singing a Paul McCartney and Wings cover.)

After that show failed, Keaton landed the lead in a sitcom, costarring with Jim Belushi as a couple of regular Joe’s in 1979’s not-that-funny Working Stiffs.

Through it all, he continued doing stand-up comedy. But “wanting to do everything” means it’s hard to get good at any one thing in particular.

“When I started, it was horrible,” Keaton told Ellen. “You’re working in front of seven people sometimes. You have to experiment. You die a lot. And I thought, ‘well, maybe I should do props.’ It’s a really bad idea because after you die, you have to pick up your props.”

More stand-up disappointment was in store when he got a gig opening for, of all people, Cher. By this point, Keaton had developed a solid set of material -- but one designed for smoky nightclubs, not cavernous Vegas dinner theaters.

“Backstage the curtains were like 40 feet high. Then you get onstage, and they’re there to see Cher,” remembers Keaton. “They’re still eating, all you hear is silverware and people mumbling things like, “Hey, I didn’t order Thousand Island.” You’re up there and they go: ‘Who is this kid? Why is he bothering us?’”

But occasional bombing wasn’t the reason Keaton eventually quit stand-up. “No one really gets — unless you’re in that world — what that world really is; what you have to do if you want to be really good and how serious it can get. I was always afraid that the fun would go away. I was always afraid that I’d 'catch the disease.' The crazy that’s a lot of times in there and the self-involvement and, at the time, the friggin’ cocaine, which was everywhere.”

It was time to turn his full attention to acting because, as he told Ellen, he wanted to be “really, really great at something.”

A comedy star is born

Ironically, leaving stand-up to focus on acting made Keaton one of the biggest comedy stars of the 1980s.

Watching Keaton’s comic routines, it’s not hard to identify the electric persona that was about to pop on the big screen. “He knew to be locked in, how it gave his onstage persona a little bit of a spark,” says pop culture writer Tim Grierson. “His observations aren’t spectacularly funny — he comes across as an actor playing a stand-up — but his edgy demeanor suggests a seemingly normal guy who might snap at any second. That tension was the fuel for his future film stardom.”

And then, snap.

"Michael had starred in a series episode directed by Lowell Ganz, who co-wrote Night Shift,” says director and fellow sitcom guy Ron Howard. “When proven movie stars were turning us down, Lowell one day said, 'If the studio would ever just cast someone perfect for the part it should be Michael Keaton. He'd kill Blazejowski. He's a comedy monster that only the network knows about so far.' Smart call.”

Night Shift, a lukewarm comedy starring Henry Winkler in a what would have been an inspired role IF he could have done it as mortician Fonzie running an escort service out of a morgue, was a modest hit. But Keaton’s performance as motormouth Billy Blazejowski is what made critics sit up and take notice.

“With the exception of one very good performance,” said Gene Siskel of Sneak Previews, “this movie could have been the Dog of the Week.” Siskel called Keaton the movie’s only saving grace, with a “very funny performance in his first feature film. He has a bright future in the movies.”

Touchstone Pictures

Siskel called it. Based on the success of that performance, Keaton turned down Tom Hanks’ career-making performance in Splash “because it was basically the same formula. Two guys, one guy's the wild guy, one guy's the other guy. The only thing I miss is that I didn't get to work with John Candy, who I loved. Planes, Trains and Automobiles—so f***ing good."

Instead, he took the lead role in one of comedy mastermind John Hughes’s first breakthroughs, Mr. Mom. Keaton played a dude who gets laid off, forcing him to stay home and watch the kids while his wife brings home the big bucks. In the early 1980s, this situation was borderline radical.

Mr. Mom included star-making sequences like Keaton proving his manhood to his wife’s new boss. " Mull comes over in the morning to pick up Teri Garr, who's gone back to work, to take her on a business trip. My guy's been fired, he's staying at home, he's really emasculated,” says Keaton.

So Keaton needs to find his inner man. “We're doing the scene and I remember saying to the prop guy, 'Go find me a chain saw.' When he comes back with it, he says, 'You wanna wear these?' And he holds up some goggles. I go, 'Yeah.' You know, they make me look crazy. So we're standing there, Martin pulls me aside and says, 'You know what you ought to say? When I ask about the wiring, you oughta just deadpan: '220, 221.' I died. It was perfect. I may have added 'whatever it takes.' But it was his."

Keaton was officially a comic star. He made more comedies, including outright bombs (Johnny Dangerously with hot-in-the-moment Joe Piscopo) and dated missteps (the what’s-happening-to-the-American-worker film Gung Ho).

He was also an early Letterman favorite. Like Andy Kaufman, Teri Garr, and Bill Murray, Keaton was clearly one of “Dave’s guys,” a new generation of funny people who were too hip for Carson. His late-late-night appearances only solidified his comedy cred.

But to unleash the full power of his snap-at-any-second unpredictability, that dangerous comic quality Keaton had displayed in Night Shift, he’d need to team up with another comedy weirdo -- director Tim Burton.

Beetlejuice, Beetlejuice, Beetlejuice!

Like Splash, Keaton originally turned down Beetlejuice.

“I didn’t quite get it,” Keaton told Rolling Stone, “and I wasn’t looking to work.”

The script’s original spook was more evil, less funny -- but Burton invited Keaton to give it his own manic spin.

The Geffen Company/Warner Bros.

“I went home and thought, ‘Okay, if I would do this role, how would I do it?’,” Keaton says. “It turns out the character creates his own reality. I gave myself some sort of voice, some sort of look based on the words. Then I started thinkin’ about my hair: I wanted my hair to stand out like I was wired and plugged in, and once I started gettin’ that, I actually made myself laugh. And I thought, ‘Well, this is a good sign, this is kind of funny.’”

Critics agreed. “The nuthouse Keaton not-so-surprisingly steals the show in his field-day performance,” said the Hollywood Reporter’s review. The Guardian praised Keaton’s “scene-stealing gusto … he is a bundle of scuzzy, lecherous, manic energy – somewhere between Robin Williams, Jack Nicholson and Krusty the Clown.”

“I’ll tell ya,” says Keaton, “I feel very good about being part of a project that has broken some rules and is at the very least innovative, imaginative, creative – just plain funny.”

The manic smile, the sunken eyes, the wild, stringy green hair -- it’s hard to believe Keaton’s Beetlejuice didn’t inspire some later performances.

Warner Bros.

Yeah, Beetlejuice was basically the Joker causing mischief in the afterlife. So it wasn’t a surprise when Burton came calling again when it was time to make his Batman. The shocker was that he wanted Keaton to play the hero.

“Michael Keaton is basically an ordinary guy, a regular human being,” Burton told the Wall Street Journal about the casting. “I thought it would be much more interesting to take someone like that and make him into Batman. I met with a number of very good, square-jawed actors, but the bottom line was that I just couldn’t see any of them putting on a bat suit.”

It was an inspired choice, although one that put an end to a long run of massively popular comedy roles. The reimagining of who Keaton could be was likely tremendous for the actor’s career. But it may have also cost us a few more years of the high-wire comedy act that defined him for a decade.