Animators Once Threatened Walt Disney With A Guillotine

Like any American megacorporation, Disney tolerates unions about as much as it tolerates park visitors dumping their loved ones' ashes into the bushes next to the Magic Tea Party ride. But one department within Disney has enjoyed relatively smooth labor practices for over 75 years now. And all it took them was to show Walt Disney they were willing to start a violent workers' revolt if he didn't start paying for their overtime.

Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Archives

Despite lowball contracts, 12-hour day/seven days a week level crunches, and the constant fear of getting fired by Walt for having the wrong opinion or not letting him win at the company softball game, early Disney animators would have never dreamed of forming a union. This was in large part thanks to Disney's generous bonuses and profit-sharing schemes which made his animators the best paid commercial artists in Hollywood. This changed in 1937 when a near-bankrupt Disney ceased all bonus payouts expecting Snow White and the Seven Dwarves to be a box office bomb. But when the movie turned out to be a smash hit, the magnanimous, meritocratic Disney immediately took those profits and … pumped them into the construction of a glamorous new studio in Burbank.

Don't Miss

Over the next years, the financially struggling Disney continued dropping wages and workers. Until, in 1941, a majority of the Disney animators led by legendary animator Art "Bones" Babbitt decided to join the fledgling Screen Cartoonists Guild and threaten to strike if fair labor demands weren't met. Shocked by this betrayal, Daddy Disney tried to reason with the upstarts like any good family man capitalist would: he fired several pro-union animators, created a dummy union controlled by his fixer, hired a union expert/violent New York mobster to handle the negotiations, ... He even jumped atop an apple box and gave a speech, calling people who want fair wages lazy and threatening that any employee who joined a union would no longer be allowed to use his pool during company cookouts.

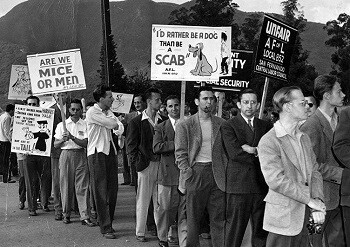

Staring down the threats to their livelihood, health, and pool privileges, hundreds of artists went on strike anyway. Joined by many high-status employees (including Disney's Head of Sanitation, His Serene Eminence Count Hugo D'Arcy of Italy), hundreds of Disney Animation staffers surrounded the House of Mouse and started a picket line. This was when Walt learned an important capitalist lesson: cartoonists are really good at protesting. The strike immediately drew massive media attention as the animators used Disney's mascots against itself, adorning their protest signs with the likes of Jiminy Cricket declaring: "Taint Cricket To Pass A Picket." Or Pluto saying, "I'd Rather Be A Dog Than A Scab."

Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Archives

It didn't take much for Walt (unsurprisingly) to start taking the strike personally. Refusing to give the unionists an inch, he instead tried to have them arrested, branded as Communists, and tried to get into a fistfight with Babbitt during one picket driveby. The picketers also became combative as the strike dragged on. Chants grew aggressive, scabs would get their cars keyed, and once a week, in collaboration with their comrades from Warner Brothers Animation, they would wheel out a life-sized, functioning guillotine and decapitate a straw dummy of either Disney or Disney's lawyer while singing a Disneyfied version of La Marseillaise.

But while the strikers suffered in the blistering sun, the Disney Company was suffering far more. By the second month of protesting, the studio was being boycotted by half of the Hollywood shops, making it impossible to continue making, let alone make money off, their ongoing projects. But a bitter Walt Disney still refused to start negotiations. Things got so bad that President Franklin D. Roosevelt (who was a little busy with a little thing called World War II) had to intervene, sending two federal judges to Burbank to mediate. When even that failed to pressure Disney into talks, the U.S. government concocted a ruse luring the mogul out of the country on a bogus propaganda tour of South America. This gave his brother Roy Disney enough time to hash out a deal with the Guild.

By the time Walt returned, the Labor Department had already ratified the union agreement, granting all Disney animators increased wages, health insurance, a standard 40-hour workweek, and, finally, a screen credit on the movies they helped create. Legend has it, Walt was so angered by these concessions that in an act of petty revenge, he added a scene to Dumbo depicting Babbitt and other prominent unionists as drunk clowns who go out to literally "hit the big boss for a raise."

According to Babbitt himself, this slight was pure fiction -- the clown scene had been created long before the strike had started. The real slight was far worse. Instead of appearing in the quickie scene, Babbitt was forced to work on it -- a job far underneath his talent and position in the company. The same sidelining befell the other picketers as an embittered Walt spent the next years cultivating such an unwelcome environment for Babbit and the so-called traitors that, by 1950, almost all of them had moved on. But while Walt could bully the union fighters into going away, he couldn't do the same to the union benefits. And with Disney's animators on board, every animation studio in the country joined the Screen Cartoonists Guild, which later morphed into The Animation Guild -- a powerful force for fair labor practices that every American animator owes to the brave men, women, and guillotines of the Disney Strike of 1941.

For more weird tangents, do follow Cedric on Twitter.

Top Image: Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Archives