Why Ebert Is Wrong: In Defense of Games as Art

If you're a fan of inter-generational bitching and anonymous bickering over abstract concepts, you're in luck! Roger Ebert is stirring the hornet's nest again. Actually, that might be too mild a descriptor for what he's doing, but "urinating in a hornet's nest full of nerds" is a much less familiar saying, so the understatement will have to stand for now. Once upon a time, long, long ago, back in the frontier days of the Internet, Roger Ebert wrote a blog that scarred the burgeoning gaming community for years. Yes, all the way back in 2005--when you were lucky to get a byte all to yourself and "MMORPG" was just the sound you made when you got hit by a truck--Roger Ebert stated, unequivocally and without exception, that video games are not and could never be considered "art."

Operating under the assumption that if you go on public record as being broadly, stupidly, ignorantly wrong one time, you may as well do it repeatedly and loudly, he's bringing up the debate again"From now until the stars go dark, I decree that this so-called 'painting' crap shall never be art. Let it be known!"

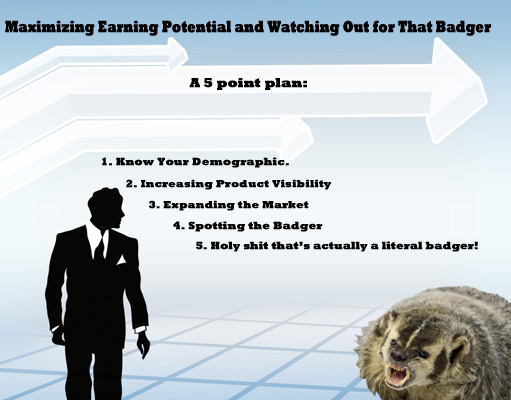

Now, I'm not a guy who loses respect for somebody because they voice opinions which I consider ill-informed or monstrously retarded--hell, some of my best friends are ill-informed and monstrously retarded, and I'm the only person I trust enough to callThe next slide is a tutorial acronym for staunching the bloodflow from a severed femoral artery using only supplies you can find in your cubicle.

So how does Roger Ebert's rationale justify having such a severe opinion on something he freely admits to never experiencing? In his words, he understands video games thusly: "By the definition of the vast majority of games. They tend to involve (1) point and shoot in many variations and plotlines, (2) treasure or scavenger hunts, as in "Myst," and (3) player control of the outcome. I don't think these attributes have much to do with art; they have more in common with sports." I'll concede that point. Most games are more like entertainment than art, but condemning the few because of the many is faulty reasoning. By that same logic, my understanding is that the definition of movies is pornography. If you're factoring in Internet sites, amateur efforts and the vast machinery of constant orifice violation that I'm pretty sure most of California has turned into by this point, then pornography is the most prevalent use of film. Or if that example doesn't work for you: Movies are commercials. There are more commercials on television by sheer airtime than there are movies in the world, therefore that's what all film is. Would you take me seriously if I began a tirade against the value of cinema by stating that movies shouldn't be taken seriously because, by volume, most of them are surveillance recordings of parking lots, 7-11s and ATM Machines?"Man, I don't get why you like these things. The characters are shallow at best and the plot is practically non-existent."

But hell, let's even roll with Ebert's faulty definition and just talk about the blockbusters. So first off, must something be judged in its entirety to be considered art? Is there not art in fleeting moments? Look at Children of Men: I'm not sure if I'd classify that movie as a work of art, but there's one pivotal scene where, after an hour or so of relentless tension, action and pursuit, the main characters leave an apartment building--currently the scene of a tremendous firefight--holding the first baby anybody has seen in decades. And everything just stops. The soldiers stand dumb-founded and slack-jawed, the soundtrack of booming explosions and rattling gunfire cuts out, leaving sudden, stupefied silence. The abrupt switch of pace is jarring enough to drive the scene's point home: There are conditions where even the most hardened and violent people can be awed by the sanctity of life. That moment was art. Fifteen minutes prior, Clive Owen kills a dude with a car batteryThe kind that smashes your head in with car parts. It's big in Europe.

For the gaming equivalent of that, take Call of Duty: Modern Warfare. That game, despite being entertaining and well-balanced, was dumber than a bag of rocks after a childhood spent in the American education system. It was big, it was loud, it was the epitome of pointy and shooty. But then, after you've spent several hours blissfully sprinting through exotic locales and exploding new and interesting people, this scene happens: A nuclear bomb goes off, and you're suddenly no longer playing the invincible super-soldier, you're playing the part of the dead and dying. There's no shooting here, no treasure or scavenger hunts and, not to spoil anything, but the player has no control of the ultimate outcome. It's the gaming aspect of this moment that makes it work: Your entire history of playing video games up until this point had conditioned you to believe that death is a just a momentary loss. Death is a tackle or a missed shot. If you die, you simply set yourself up better, and do it over again. Sure, other games would kill characters off in a cut scene, but up until CoD4I see what you did there.

Ebert believes "the real question is, do we as their consumers become more or less complex, thoughtful, insightful, witty, empathetic, intelligent, philosophical (and so on) by experiencing them? Something may be excellent as itself, and yet be ultimately worthless." Sure, most games fail to live up to that criteria. So do most movies, books, paintings and songs. I could list off some of the more underground games that make the best case-by-example of the game as an art form – but Ebert and people siding with him would not play them anyway. They'd read a synopsis, and dismiss them by it: Like how Braid"Fuckin'... fuck this thing! Purple is my jam; that's all I'm trying to say!"

As a game, Rez was not great fun--it was a rail-borne "shooter" where you didn't really "shoot" so much as select vast swathes of targets--but its presentation was brilliant. Rez inextricably tied the player's every action to the beat of the music, which changed and evolved along with your actions and play-style. The visuals, in turn, changed and evolved with the music. All of the senses in Rez crossed with one another, integrated into each other and bled into another in some way, shape or form. If Kandinsky painted to explain his Synesthesia to others, Rez actually let them experience a small portion of it. Rez shares a more complete Synesthetic experience than Kandinsky's paintings simply because of the player's involvement in it. For this one, particular arena, the less interactive medium (painting) is essentially crippled. That brings us back to the question: What is art? Is it the object produced or the experience shared? The former sounds more like consumerism to me, but the latter sounds about right. And if that's the case, I say Rez...and possibly bashes its head in.

But why even bother with all of this? Ebert himself wonders: "Why are gamers so intensely concerned, anyway, that games be defined as art? Bobby Fischer, Michael Jordan and Dick Butkus never said they thought their games were an art form….Why aren't gamers content to play their games and simply enjoy themselves?" And he's already answered his own question: "do we as their consumers become more or less complex, thoughtful, insightful, witty, empathetic, intelligent, philosophical (and so on) by experiencing them?" Anybody who's ever felt even an inkling of something like that from a game is going to be understandably "concerned" when you insist that they're lying.You can buy Robert's book, Everything is Going to Kill Everybody: The Terrifyingly Real Ways the World Wants You Dead, or find him on Twitter, Facebook and his own site, I Fight Robots or you can reconsider buying his book. It works miracles. This kid in Canada bought it, and now he speaks near-perfect English... practically overnight!