The 5 Best Pieces of Writing Advice You Don't Get in School

As readers of a site that welcomes and encourages submissions, there's a decent chance some of you want to be writers. Several months ago, I wrote an advice column on how to go about freelancing for the Internet and magazines, but some readers have their sights set on short fiction or even novels. And right now, some are contemplating education choices like picking a major or attending graduate school to get that MFA.

Let me be clear: Education is wonderful. There is nothing you will ever learn that you will not ultimately use. Conceptually, I am fully in support of a liberal arts education, even when there is no obvious and immediate application of that knowledge to daily life. However, with rising costs in an appalling economy, racking up that debt seems harder to justify, and I find myself agreeing more and more with a column Robert Brockway wrote years ago questioning the need for college. I'm not going quite that far yet, but I have soured on graduate programs -- particularly MFAs. (Brock's still wrong about Nirvana's cover of Bowie's "The Man Who Sold the World" being superior, by the way.)

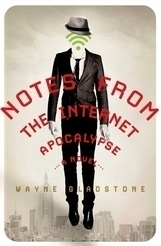

It's a very personal choice, but consider this: Every important thing I've learned about writing I learned from a writer. Yes, one of those writers was a college professor (not grad school), but for the most part, I got all my best storytelling lessons from interviews I saw on TV or read in books. That makes sense, right? Who better to explain writing than writers? And yes, of course many MFA programs employ distinguished writers who can impart these lessons to you directly, and that's great if you can afford it, but the knowledge is out there. Writers are showoffs who like to talk and give advice, and they like talking about writing most of all. Every one of these tips below can be learned for free, and I promise you, I could never have written my forthcoming novel, Notes from the Internet Apocalypse, without them.

There's No Such Thing as a Flashback -- It's a Flashpresent

When I was a teenager, I saw a documentary about Academy Award-winning screenwriter Waldo Salt called Waldo Salt: A Screenwriter's Journey that never left me. Salt's particular area of expertise was adapting novels for film, and to do so, you need to understand the differences between the two mediums. Nevertheless, one of the lessons he gave applies equally to film and novels: There is no such thing as a flashback -- it's a flashpresent. Another industry giant, Syd Field, explains what that means here, but basically, flashbacks deliver vital information and, when done correctly, should inform you about the character.

If you think of a flashback done badly, it's a mere plot device -- a data dump where the screen goes all hazy and some facts are delivered to you.

The kind that Wayne's World used to make fun of: "Doodoodoodoo doodoodoodoo ..."

The goal is to use the flashback less like a device and more like a memory. After all, there is no need for a flashback to be hokey. We all carry memories with us through our lives, and they come out when they're triggered by the things we're doing. That's what Salt's getting at. In order for a flashback to justify its existence, it needs to make sense to the action of the moment. If you use it that way, you're not only compressing action into a tighter story -- vital in both screenwriting and novel writing -- but letting the reader understand the character in a deeper way.

There's another secret perk of using flashbacks: If you do it the right way, as Salt suggests, then it forces you to have a deeper understanding of both the past and the present of your character. You will have to ask yourself why your character is thinking and feeling this, and you will create the through line of the character's life from that past moment to the present. When I got back the edits from my novel, the copy editor stumbled over the very first flashback of the book. He wrote, "This action feels like it's happening in the present." It was the best accidental compliment I've ever received.

Hide Plot Points With Humor

John Cleese, founding member of Monty Python, creator of arguably the greatest sitcom ever, Fawlty Towers, and writer and star of the classic A Fish Called Wanda, has taken to lecturing on the creative process recently, but the point that has always stuck with me came from an interview he did in the '80s about his goals for Fawlty Towers. Cleese explained that he wanted to stray from conventional sitcoms where they just drop the plot on you in the first five minutes. Think Saved by the Bell:

Cleese explains that when he was writing the show with his then-wife Connie Booth, they always made sure that when a vital plot point was delivered, they would make it as funny as possible. The goal was to trick the audience into processing the information without realizing they'd been given it. Anyone watching would assume that the structurally significant scene was added solely for laughs.

That leads us to another more general point: You have to accept that writing is a trick. Every time you make a reader laugh or cry, you have used manipulation. Don't let that upset you. Readers want to be tricked. It's why we go to magic shows. We know that lady isn't really levitating, but we crave the moment of maybe and magic. It's the same with readers. We accept that stories are made up for our enjoyment. Writers who hide their trickery are not mean-spirited deceivers; they're just magicians who take the time to conceal the strings well enough to give their audience the gift of wonder.

Don't Drain the Well

When people think of Ernest Hemingway's writing advice, they usually stick to "write the truest sentence you know." That's good advice, especially if you're prone to a fanciful, but ultimately boring, imagination, but it's not the advice of his I value most. Here's my favorite bit of Hemingway guidance:

I learned never to empty the well of my writing, but always to stop when there was still something there in the deep part of the well, and let it refill at night from the springs that fed it.

That's crucial. We've all heard the maxims that writers write and that Stephen King writes 1.2 million words a day on a specially fitted typewriter that allows him to use all 21 of his appendages to type words on paper that prints directly into bound hardcover books, but when do you stop writing? That's important, too, and I think what Hemingway is getting at is that novels are a lot like daisy chains.

What I mean is, they're connected. One scene leads to the next to form a full story. More importantly, writing often comes best when you're about 85 percent sure of where you're going. Sometimes, if you see the scenes too clearly, the magic disappears and you (or at least I) feel like a mere reporter of events. But if you stop while there's still a little left -- if you don't record every known thing in your imagination, but keep thinking about it -- something happens. Something J.D. Salinger said comes true:

No, no, no. He never said that!

Salinger said, "Novels grow in the dark," meaning that even when you're not actively working on them, your unconscious mind keeps building details. If you apply Hemingway and Salinger together, the little you leave "in the well" each time you write will "grow in the dark" and, ideally, when you come back to write again, you'll have more thoughts to get down on paper. Each newly formed idea will lead to another, slowly building. Then you can go back and edit to more fully understand your journey and focus it just enough toward the future. That's how it works for me at least -- I mean, if Hemingway and Salinger weren't good enough references.

Don't Be Consumed With Being Original (The "Ice Ice Baby" Test)

I've never had writer's block for the same reason I've never had the lasagna at the Olive Garden: It just seems terrible and I don't want it. But from about 18 to 28, I did mercilessly reject a lot of my own ideas for not being original enough. It wasn't writer's block. If you pointed a gun at my head, I could have written those ideas, but I made a decision to only write what I liked. There's a difference. And it was a bad decision, because "not being original enough" is usually a bad reason for not liking something. There are countless important stories in the world that follow the same structure over and over, whether it's the Bible or Superman or Star Wars. Don't let similarities stifle you. Indeed, they're liberating.

Blake Snyder wrote a great, but sometimes maligned, screenwriting book called Save the Cat, which includes his beat sheet where he lays out the essential framework of a three-act play or movie. It works equally well for novels, and I used it for Notes from the Internet Apocalypse. Is that cheating? No. You can break the rules, you can do whatever you want, but you should find a certain comfort knowing that there is a structure that produces stories that work, whether they're Schindler's List or Legally Blonde. And there's another important realization: Despite identical structure, those movies aren't anything alike. There is plenty of opportunity for you to be you.

But how do you know when you're a plagiarist and when you're doing something that merely reflects other elements while retaining your own soul? I came to that realization later in my writing life with the help of J.K. Rowling. I mean, think about Harry Potter. Aren't the muggles like Roald Dahl characters, isn't some of the gross-out humor Pythonesque, isn't Ms. Umbridge's pen a heck of a lot like Kafka's torture device in In the Penal Colony, and isn't the quest to destroy horcruxes while resisting their corrupting influence noticeably reminiscent of Frodo's journey to destroy the Ring? Yes, yes to all, but Harry Potter is still an awful lot of fun filled with compelling storytelling. So how do you tell? Well, in an earlier article and a lecture, I laid out what I like to call the "Ice Ice Baby" Test:

Essentially, I think sampling in music is an excellent analogy. Take a great song like Beck's "Jack-Ass." Sure, he takes the opening of Them's "It's All Over Now, Baby Blue" and loops it prominently, but that's only the starting point. He overlays new chords and melodies to create a piece of music. Conversely, look at Vanilla Ice's "Ice Ice Baby," which is built on Queen and Bowie's "Under Pressure." Ask yourself, what is the enjoyable part of "Ice Ice Baby"? It's the bass riff, right? It's the part of the song Vanilla Ice had absolutely nothing to do with creating. And that's how I feel about writing. No one reads Harry Potter looking for Rowling's Kafka allusions; it's just mixed in with her own original story about a school where strict rules of conduct are laid down and then repeatedly broken for the good of one special boy.

So yeah, before you kill your own ideas as cliche, maybe write them out a bit and see if you're building something worthwhile and new on the backs of your influences.

Ask "What Do You Want Your Readers to Feel in the White?"

Of all the tips I learned on this list, this is the only one taught to me by a professor at an actual school. Still, it was an undergrad program, so I don't think that ruins the conceit of this article. At Cornell, I was lucky enough to have Professor Dan McCall as a writing instructor and thesis adviser. Unlike most writing teachers, Dan would read the students' short stories out loud to the class himself. He forced you to hear your own words, not as you polished them in your delivery, but how they existed on the page. By doing so, he showed you the sounds your writing made. He let you know what kind of mark your prose was leaving on the world.

So it makes sense that the piece of Dan McCall advice that I took with me most was that every writer should be aware of what they want the readers to feel "in the white." He was referring to the end of the piece, that white space between the last line and the bottom of the page. If a piece of writing is any good, you should be left feeling something there.

If all this advice did was make sure you ended your stories strongly, that would be enough. After all, who doesn't like a powerful ending? But much like good writing, this advice is a trick. You can't end strongly by worrying only about the last few sentences. It's like sticking a killer punchline onto a poorly told joke; it won't work. If you're really concerned about what your readers will feel in the white, then you have to make sure you're setting up an ending from the very beginning, and if you're doing that, well then you're worrying about every part of your book.

Dan died this past year, before I could tell him my first novel was going to be published, but not before I got permission to give one of my characters his name. The character's a clairvoyant with an encyclopedic knowledge of science, history, and pop culture, but he's not half as impressive as the real Dan McCall, a man who could redirect both you and your writing with just a raised eyebrow or a sarcastic laugh that somehow still comforted as it pointed you a better way toward home.

GLADSTONE'S NOTES FROM THE INTERNET APOCALYPSE IS NOW AVAILABLE FOR PRE-ORDER!

After experiencing the joy of pre-ordering Book 1 of the trilogy, be sure to follow Gladstone on Twitter.

Also, you can get all your Internet Apocalypse news here as we count down to release.

Always on the go but can't get enough of Cracked? We have an Android app and iOS reader for you to pick from so you never miss another article.