3 Things the Internet Always Gets Wrong

The Internet is about convenience. It saves us time doing research, getting directions, and finding appropriate masturbation fodder. Hurray! But there's more. Spend some time in forums and comment sections and you will see that the Net also provides a crash course in philosophy, theology, and logic.

"Newton's third law of motion dictates that you're a douchebag."

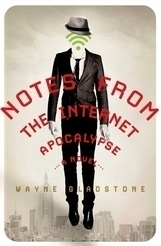

However, this is a column all about what the Internet gets wrong, and as I wrote in Notes from the Internet Apocalypse, the problem isn't the Internet: It's people. Any device that brings people together and lets them talk and argue freely will showcase the limits of humanity and our desperate need to make things bite-size and simple. That's no great tragedy when people go online to trade hashtags and cat memes, but the way we reduce important thoughts and theories to one-liners is a little disconcerting.

And we love to do that. Now, instead of developing our arguments or citing deep thinkers in a way that appropriately supports our views, we simply name theories and laws before dropping the mic, as if we must be right because our point's got a fancy name. But theories almost always come with counterpoints, and 9 times out of 10 the Internet just cites things wrong. Here are three theories the Internet won't stop abusing.

Russell's Teapot

This argument has been paraphrased by the Internet so badly that many won't recognize it by name. It's used in support of atheism, and in its original formation, before Ricky Gervais made it fun size, it was a good one.

"Gervais' Teapot? Ricky's MePot. Yes!"

What It Actually Says:

Those who insist that others should believe in God have the burden of proof.

Bertrand Russell was a noted philosopher, mathematician, and atheist. Russell rejected the Christianity he was born into and argued that those who insisted on the existence of God to others had the burden of proof. To explain why those making assertions should prove their theories, he gave an analogy about a teapot in space:

Many orthodox people speak as though it were the business of skeptics to disprove received dogmas rather than of dogmatists to prove them. This is, of course, a mistake. If I were to suggest that between the Earth and Mars there is a china teapot revolving about the sun in an elliptical orbit, nobody would be able to disprove my assertion provided I were careful to add that the teapot is too small to be revealed even by our most powerful telescopes. But if I were to go on to say that, since my assertion cannot be disproved, it is intolerable presumption on the part of human reason to doubt it, I should rightly be thought to be talking nonsense.

But do you see the context of the statement? It's a reaction. It's a reaction to orthodox, dogmatic people. Personally for Russell, even if he disclaimed all religions, it's a reaction to the Church of England. It's a reaction to those who want to proselytize and tell you you're going to hell unless you agree with them. It says to those people, "Hey, back off. I would never have the audacity to insist that you believed something stupid about a teapot."

I fully agree with Russell on this, but I hate the way it's used.

How It's Used Now:

Believing in God is as stupid as believing in outer space teapots!

Most of the time you see this idea referenced without the inclusion of it being a reaction to those who are "orthodox" or "dogmatic" and who find the questioning of their beliefs "intolerable." Instead, the Internet reduces the argument to something along the lines of ...

"If you believe in God, you might as well believe in outer space teapots, derpity derp derp."

There's a reason people online get it wrong: The Internet assumes it's a fight. It assumes any person of faith wants you to believe as they do. Wants to prove you wrong. Wants to damn you for not reading from the same holy books. And if you find those people who are telling you you're going to burn in hell because there's something wrong with you for not accepting the blood of Christ or whatever faith is being preached, you'd be in your rights to cite to Russell. You could say, "Hey, don't tell me there's something wrong with me for not believing as you do when it's your job to support your incredible claims before attacking someone for not being of a similar mind."

But too often, the Russell's teapot rhetoric is used as a dig on anyone of faith. Even those minding their own business. There are millions of people in the world who believe in God and do not care at all if you do, too. There are millions of people who belong to religions that don't even try to win converts. Citing Russell with them is nothing more than a bullying tactic that tells them their religious faith in an unprovable god is as stupid as believing in celestial teapots. I'm sure I can't stop you from doing so if that's what makes life worth living for you, but it is a perversion of Russell, whose argument is designed in response to the dogmatic and intolerant.

Godwin's Law

While the theory above might have been unknown to you if you're the type of sane individual who avoids arguments on religion, there's no way you've escaped Godwin's law -- even if you don't know it by that name.

This Internet adage was coined by attorney and author Mike Godwin as he sought to address the incredibly lazy rhetorical arguments of people online.

"Coining Internet adages? Why didn't he just write a list about 5 Ways People Online Suck?"

In a piece for Wired, Godwin wrote:

As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches 1.

What It Actually Says:

The Internet goes too far with Hitler comparisons, thereby cheapening the Holocaust.

While Godwin first made this assertion regarding Usenet newsgroup discussions, it's been applied to any online comment thread. Basically, Godwin was irritated by the people he saw "playing the Hitler card" over and over, and he wanted to start a meme to curb such use. As Godwin wrote:

Stone libertarians were ready to label any government regulation as incipient Nazism. And, invariably, the comparisons trivialized the horror of the Holocaust and the social pathology of the Nazis. It was a trivialization I found both illogical ... and offensive.

"School lunches supported by tax dollars? JUST LIKE HITLER WOULD DO!"

How It's Used Now:

If you mention Hitler in any discussion, you lose!

While Godwin was certainly seeking to end weak-minded, easy, offensive references to Hitler, for many, his adage has devolved into a simple "If you say 'Hitler' during an argument, you lose." That is a perversion of his words that clearly goes too far. Godwin's law seeks to curb the abuse of faulty historical comparisons, not remove them completely from any online discussion. It's fair to say that references to Hitler probably shouldn't come up in discussions regarding climate change and public smoking bans, unless you have a child's understanding of history or the same child's petulant intolerance for anyone disagreeing with you. Nevertheless, issues of genocide, racial superiority, and extreme fascism still exist in the world. And the Internet will talk about it. It will argue about it.

"Nice try! You said 'Hitler' while we were discussing the neo-Nazi movement. Game over!"

Poe's Law

Who would have guessed that people debating religion would produce so much vitriol and misunderstanding?! Anyway, back in 2005, Nathan Poe noted on ChristianForums.com that without other indicators of humorous intent, it was virtually impossible to differentiate mocking trolls from devout believers in the comment threads. Or, put his way:

Without a blatant display of humor, it is impossible to create a parody of extremism or fundamentalism that someone won't mistake for the real thing.

What It Actually Says:

Some people can't tell the difference between mere trolling and statements of sincere extremism.

Much like Russell's teapot, context is everything. Poe's law was born on a site for creationists -- a decidedly extreme and literal-minded people, what with actually believing in a woman born from a man's rib and talking snakes and apples and stuff. And let's not forget the other people on creationist sites: trolls. The kind of people who are great at coming up with super cutting and clever zingers like:

"Nice hat!"

Or:

"Great job!"

Poe's adage is right. Sometimes it is hard to tell the difference.

How It's Used Now:

Satire doesn't work and shouldn't be tried.

Having said that, I'm nothing short of disgusted by the way the Internet drops "Poe's law" every time there is outrage over some comic's satire. In my last column about satire, in which I addressed controversies around Stephen Colbert, Andy Levy, and Patton Oswalt, I saw comments from people basically saying that satire doesn't work online. And while they were certainly emphatic, they were also, of course, wrong. Incredibly wrong. Any expression of art or humor can always be misunderstood or fail in any medium, but Poe's law about mere sarcasm being mistaken for the extreme rhetoric of the devout is not a cautionary tale about the death of satire.

Shockingly, literary scholars now realize there were NO ":)" or "jk" or even ";p" in the most seminal satiric work in history!

And it's particularly important to get this right, because satire is already under attack in this country. There are many reasons satire can't get a break. Certainly, people being stupid is a popular refrain, and I've written about that twice. More recently, I thought the problem might not be a lack of brains so much as a lack of faith in the satirists themselves. And while I still believe both those thoughts are valid, more recently I realized that for some, the problem with some forms of satire comes from a steadfast belief in the merits of political correctness.

Why is a big stinking liberal like me hostile to the PC movement? Well, mostly because I care about how racial and religious minorities are treated. I am in favor of a world where women feel safe and receive equal pay for equal work, unhindered by the government's interference with their health decisions. I support gay marriage and adoption. And I don't believe mere political correctness -- the selecting of approved terms and words with a knee-jerk rejection of anyone not on board with dictated vocabulary -- gets us those things. Especially not when it prevents artists who obviously also care about such things, like Stephen Colbert and Patton Oswalt, from pursuing their liberal-minded agendas.

Today, it's not uncommon to hear people say, "Oh, I get that it's satire, but it's failed satire because it's offensive." What those folks don't understand is that it's more likely failed satire if it doesn't offend someone. Causing offense is one of the main tools of satire: to invoke outrage at fiction so that the viewers or readers then take all that aggression and direct it at the real target. That is exactly what Jonathan Swift did with A Modest Proposal. He catalyzed people's horror at suggesting infanticide as a poverty solution so all those emotions could be channeled toward those who are indifferent or clueless about the poor's suffering. And that is what Stephen Colbert did with his now infamous Dan Snyder skit. He took all the outrage at his obviously racist suggestion for a "Ching-Chong Ding-Dong Foundation for Sensitivity to Orientals or Whatever" so that it could be focused on the very real enemy of Dan Snyder half-assedly attempting to excuse the offensive "Washington Redskins" name by supporting bogus organizations.

This is not a joke.

Many said that Colbert simply wasn't allowed to create such satire because he had to be politically incorrect on his way to attacking racism. As such, political correctness has become the enemy of satire, because part of satire is saying awful things you don't mean to direct ire toward the real enemy. People who put PC first say, yeah, yeah, but you had to use "those words" to attack racism, so no dice. Those are flawed priorities. An art form such as satire has a greater ability to change the hearts and minds of people than adherence to a mere list of approved terms. And as they're society's best hope for social change, I never want to see satirists have their hands tied behind their backs in deference to PC.

If you want to disagree with that assertion, I know I can't stop you, but do not point to Poe's law as your defense. Poe's law recognizes the difficultly of differentiating mere sarcastic trolling from sincere, religiously literal views on creationism. It does not dictate the death of satire as a force for social change. That only happens if we let it.

GLADSTONE'S NOTES FROM THE INTERNET APOCALYPSE IS ON SALE NOW!

After experiencing the joy of purchasing Book 1 of the trilogy, be sure to follow Gladstone on Twitter.

Also, you can get all your Internet Apocalypse news here.