6 Bedtime Stories In History Creepier Than Our Horror Films

Now that it's become abundantly clear that we are never, ever, EVER going to be done with the Harry Potter franchise, it's worth our time to try and understand why we just can't quit the Boy Who Lived. Well, looking back at some successful children's franchises of the past, we think we might have an answer:

We're suckers for anything that wants to kill children.

No, really, that's it. History's forgotten children's books prove that at the end of the day, a lot of people want to either scare kids to death or see pictures of dead and dying children in literature.

Fantastic Beasts And Where To Find Them's Prototype Made The Woods Terrifying

Picture yourself as a kid in 19th-century America, back when electricity was barely a thing, every town was surrounded by seemingly endless forests, and the concept of science was only a couple of hundred years old. Those forests that surrounded your town were probably the scariest thing in your world besides infection, which was probably why every fairy tale from Little Red Riding Hood to Hansel And Gretel to Ye Olde Blair Witch incorporated the woods in the narrative.

And why Shrek warned of donkey-dragon hybrids.

After a while, Americans had their own set of wood-centered folk tales and one guy collected them in a 1910 anthology called Fearsome Creatures Of The Lumberwoods. Unlike their European predecessors, these stories explained the horrific accidents and strange phenomena the average logger stood a chance of experiencing during his time among the trees. It's basically the estranged, drunk, flannel-wearing uncle of Fantastic Beasts And Where To Find Them.

Among the creatures listed in the book was the Hidebehind, an intestine-eating monster that hates alcohol so much that the only defense an honest logger has is being drunk as often and as thoroughly as possible.

It's not actually that good at hiding, or cleaning up afterward.

Then there's the Dungavenhooter, which will beat you into gas and f**king huff you like a high schooler with a fistful of markers. They actually prefer drunks -- the Dungavenhooter, not the kids -- so it's theoretically impossible to protect yourself from both a Dungavenhooter and a Hidebehind. This presents quite a conundrum for the aspiring lumberjack... or anyone who has to go into the woods for any reason.

Hank there gets by drinking liquid ecstasy.

What about the Agropelter, which'll cave in your skull and rip your arms off? They were said to specifically hate loggers, rather than human beings in general. Think of them as hyper-aggressive Loraxes; they don't just speak for the trees, they break off pieces of those trees and bash unsuspecting lumberjacks in the dome with them.

And break pieces off you too, of course.

The Rumtifusel, meanwhile, pretends to be a fine mink coat, then wraps itself around the person who touches it and sucks him or her down to the bone with hundreds of tiny pore-like mouths. It was probably invented to explain owl pellets (they're meant to be the fluttery remains of the clothing left behind by the victims), and it's just ... horrifying.

Pictured: Something easier than explaining owl shit apparently.

The whole book is available online in full, along with a few other lumberjack-y goodies, such as Yarns Of The Big Woods and The Hodag And Other Tales Of The Logging Camps.

Struwwelpeter: Mor(t)ality Tales

Once upon a time, a doctor named Heinrich Hoffmann decided that, rather than buying a bedtime picture book for his three-year-old son's Christmas present, he would write and illustrate his own: Funny Stories And Whimsical Pictures With 15 Beautifully Coloured Panels For Children Aged 3 To 6. (Doctors are as a rule very, very specific about what they're selling you).

Being a doctor, Hoffmann's brand of humor was more likely to create a generation of pint-sized insomniacs than to whisk children (aged 3 to 6) away to dreamland. Rather than being funny and whimsical, Struwwelpeter is horrifying and bizarre and full of dead or dying children and several adult maniacs. Each story has a moral, but as with so many things dispensed by doctors, there are... side effects. Shock-headed Peter, for example, had a hygiene problem.

"Just look at him! there he stands,

With his nasty hair and hands.

See! his nails are never cut;

They are grimed as black as soot;

And the sloven, I declare,

Never once has combed his hair;

Anything to me is sweeter

Than to see Shock-headed Peter."

Lesson: Groom yourself or you'll turn into a freakish pariah even if you are only 3-6 years old.

Side effect: Learn to be cruel to children whose parents don't take care of them. They're inhuman little monsters.

There are also several stories that would be right at home in the Potterverse -- namely, the ones concerning homicidal grownups. The villain of The Story Of Little Suck-A-Thumb features a scissor-man who cuts off the figures of kids who won't keep their thumbs out of their mouths. Actually, we're not even sure if he's the villain of the story -- it sounds like the narrator really has it out for Little Suck-a-Thumb.

The door flew open, in he ran,

The great, long, red-legged scissor-man.

Oh! children, see! the tailor's come

And caught out little Suck-a-Thumb.

Snip! Snap! Snip! the scissors go;

And Conrad cries out "Oh! Oh! Oh!"

Snip! Snap! Snip! They go so fast,

That both his thumbs are off at last.

Mamma comes home: there Conrad stands,

And looks quite sad, and shows his hands;

"Ah!" said Mamma, "I knew he'd come

To naughty little Suck-a-Thumb."

Lesson: Keep your thumbs out of your mouth because I said so, not because everything you touch is covered in E. coli and MRSA.

Side effect: For every Santa Claus, there is a crazed, omniscient tailor who breaks into houses with large pairs of scissors. It's better if you prioritize not sucking your thumb over being nice.

Dr. Hoffmann's series was a hit with parents everywhere. In 1911, his stories hit American shelves in the Slovenly Betsy series, which we assure you is just bursting with the same dark, child-mauling humor that made Struwwelpeter so popular with Hoffman's Teutonic tyke-wranglers. But this instalment is less a series of side-effect-ridden lessons and more a litany of misdiagnoses of small children. Augustus, Who Would Not Have Any Soup, for example, is a fun story of a little boy who develops an eating disorder and dies.

Observe Phoebe Ann, "a very proud girl/Her nose had always an upward curl." Her problem seems to have more to do with the size of her head than the angle of her nose.

And those are the only physical problems we see here.

At first glance, "Pauline" appears to be your average prepubescent pyromaniac.

But Pauline said, "Oh, what a pity!

For when they burn it is so pretty;

They crackle so, and spit, and flame;

And Mamma often burns the same.

I'll only light a match or two

As I have often seen my mother do."

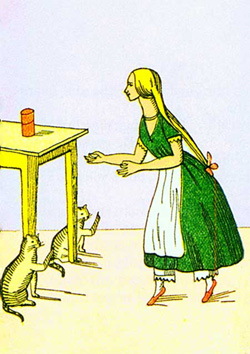

Not so! If you look closely, you'll see that loving fire is not Pauline's real problem. As she lights her matches, she has a moral debate with her two cats. They're very vocal and gesticulate freely -- to Pauline's eyes and ears, anyway. Once she lights her second match, we see clear proof that Pauline has indeed never given into her desire to light matches, before, because she Immediately immolates herself while the cats look on in horror.

Mary AKA "The Little Glutton" was actually doing fine until she made the all-too-easy mistake of trying to drink honey straight from a beehive.

Children who liked food were a major problem in the 19th century.

See, it could have stopped here, like this. "Lesson: Don't make your mom sad by eating more than your family can afford. There are serious socioeconomic implications you don't quite understand, yet."

But it didn't.

Lesson: Beehives are full of BEES.

And what about Polly, the tomboy who wanted to run and play like every child ever? After running too hard, she fell and broke her leg. Her story really says more about doctors and paramedics than children.

Lesson: When carrying a patient to the hospital, make sure to bring all of her limbs.

Not only did the doctors botch the patch up, forcing Polly to use crutches for the rest of her life, the last panel suggests that as an old woman, Polly prepared her own gravesite, complete with the commemorative crutches.

(In case you were wondering, Polly did not survive. How else will you learn?)

It is probably fitting to close Dr. Hoffmann's series of bewildering conduct-related childhood maladies with this image of a very large rabbit wearing glasses, shooting a man who is falling down a well.

The poor man's wife was drinking up

Her coffee in her coffee-cup;

The gun shot cup and saucer through;

"Oh dear!" cried she; "what shall I do?"

There lived close by the cottage there

The hare's own child, the little hare;

And while she stood upon her toes,

The coffee fell and burned her nose.

'Oh dear!' she cried, with spoon in hand,

"Such fun I do not understand."

Lesson: Just don't leave the house. Ever.

Nightmare Inkblots For The Young And Frightened

1896 was not an exciting time to be a child, but its lack of video games and cartoons did inspire a certain extra special level of creativity in adults who made toys and wrote books for the purposes of keeping kids from running amok and wreaking havoc on their parents' adrenal glands. One of these was a disturbing activity book called Gobolinks, or Shadow-Pictures for Young and Old. The Gobolink (not to be confused with the Babadook, although he would be right at home in Shadow-Pictures) is a fictitious goblin-like creature with no fixed form. The idea is simple: Participants drip ink onto scrap paper while reading the stories provided by the author and make a contest of it to see who can make the best Gobolink. Boom. Good, clean fun for the whole family.

Except... all of the shadow-pictures are unsettling as hell. They look like phantasmagoric monsters in an inkblot test for serial killers (Rorschach wouldn't start interpreting these inkblots as windows into the diseased mind until 1921 and he was a nut for inkblot parlor games). They're the kinds of things you see when you have sleep paralysis.

The Friendly Chickens look like conjoined chicken fetuses.

"Blowing crooked bubbles." Yeah, that checks out.

Dipsey Doodle and his brother "have ears like one another." (Do they? Where?)

A baffling story about crying and "feeling badly."

Hey kids! Don't be like the Bad Boy -- you'll be put in the stocks, too!

And this is just clearly a penis.

A Token For Children Cut To The Chase With 13 Dead Kids

Harry Potter is filled with lessons about love, responsibility, and the grieving process (and the grieving process... and the grieving process... after that, it's just a cornucopia of gratuitous death). This collection of stories takes it a step further by being only about that, and the only people to die are kids. At least in Harry Potter they threw in some adults.

In A Token For Children, 13 model children experience "joyful deaths." It's a... dark... collection of kids dying well, accepting their fates and handling their impending deaths better than their parents can. Some of them don't even want to be cured, and they're as young as five.

Even the cover of the book suggests a headstone.

We'll get right to it: This book is bleak. There's nothing funny about dying children, and these are, allegedly, based on actual events. That being said, the idea of other, healthy children actually reading this stuff is absolutely daffy. If you're in the mood for self-torment, go ahead and read the full stories. If not, we'll just highlight a few passages believed to encourage piety (instead, somehow, of terror) in young children.

We'll start as gently as we can with the 14-year-old girl whose life was turned upside down by her conversion and subsequent terminal illness. When she wasn't sleeping -- and sometimes when she was -- she was literally begging for death. She refused to see a doctor and spent most of her time saying things like, "How long sweet Jesus? Finish thy work sweet Jesus, come away sweet dear Lord Jesus, come quickly; sweet Lord help, come away, now, now, dear Jesus come quickly; Good Lord give patience to me to wait thy appointed time; Lord Jesus help me, help me, help me." God eventually did her a solid and let her die.

Anything to shut her up.

Kicking it up a notch was the seven-year-old boy who didn't even want to see a doctor -- he just wanted to die. This is perfectly reasonable when you consider the fact that his very pious sister was also terminally ill and would follow him to the grave three or four weeks later.

Finally (because we just can't anymore, seriously...) we're given the tale of the five-year-old boy who "in prayer ... he would beg, and expostulate, and weep so, that sometimes it could not be kept from the ears of neighbours." In the presence of swearing, he would immediately start trembling with horror. According to the book, "He was wont oftentimes to complain of the naughtiness of his heart, and seemed to be more grieved for the corruption of his nature, than for actual sin." Because of course he was. He was five. This poor boy would apparently sit in corners and berate himself for being a human being, usually while crying. Even on his deathbed, he clung to his guilt, saying, "Lord be merciful to me, a poor sinner." The author decided to end his story with the words, "He died August 8, 1664. Hallelujah."

Even five-year-olds can live in fear and die with dignity! ...Hallelujah?

The "It-Narratives" Of The 1700s Saw Inanimate Everyday Objects Come To Life

You know how every fantasy or children's movie features an inanimate object which, thanks to the magic of chicanery, comes to life and starts spouting wisecracks? We might think of that as typical of the braindead, assembly line-esque way in which modern movies are made, but in actual fact it's part of a grand literary tradition dating back to the 17th century: the it-narrative.

Behold, culture.

It-narratives tended to focus on the wild adventures of everyday bullshit like coins and pincushions, an experience you can replicate for free by visiting your nearest garage sale and dropping a shitload of mescaline.

One of the first it-narratives was The Golden Spy, a novel starring an ensemble cast of coins who team up to talk shit about their owners and the terrible state of society because fantasy is all about escapism and having fun. The books even came prefaced with a warning from the author purporting the coins' confessions had been edited down, lest they "destroy all confidence between man and man ... and put an end to human society." It was a ballsy claim on par with prefacing The Little Engine That Could with a note telling parents that letting their children read unsupervised could result in them rising up and bringing down the system.

You don't even want to know what Spot the Dog's deal is

Despite appearing on bookshelves in the days when both women were still considered conduits of the supernatural and bookshelves hadn't yet been invented, the it-narrative became the best-selling literary trend of the 17th century -- presumably, ranking alongside classics such as Eat, Pray, Die at 17 and Slaughterhouse-Tithe. The range of it-narratives then grew to encompass all manner of objects from coaches and animals to walking canes and dolls to tea cups and clothing. It's been argued that Memoirs Of A Woman Of Pleasure -- a book you might know better as Fanny Hill -- is an it-narrative of an "enthusiastic" vagina.

It was no Chuck Tingle, but it worked for its time.

Gargantua And Pantagruel Were The Terrance And Phillip Of The 1500s

The titular characters of the five-part series The Life Of Gargantua And Of Pantagruel are a duo of giants -- a father and his son, specifically. The result isn't what you'd expect of a 16th-century story; instead of thoughtful treatises on law, politics, or science, the novels are renowned for their use of gross-out humor, scat, comically gratuitous violence, and otherwise juvenile comedy. Which is awesome for those of us who make a living writing about such things.

There's a lesson in this, somewhere.

Instead of farting on people a la Terrance and Phillip of South Park, Gargantua and Pantagruel invariably shower hapless peasants and hardened soldiers alike in torrents of urine during the course of their adventures together. It's basically their father-son bonding time, like throwing a football around in the back yard. They encounter a colorful cast of cheekily named dunderheads, such as Lord Kissbreech and Lord Suckfist, and no topic is considered out of bounds; he even writes about papal approval of one's basic human right to fart freely, at one's own discretion, without being shamed by the people nearest to Ground Zero, where it is virtually impossible to hide your guilt (unless you are fortunate enough to own a dog). As a bonus, there are a number of chapters containing long lists of rude and ribald insults ready made for use in whatever way you, gentle reader, deem fit.

"He did cry like a cow!" (It loses something in translation.)

One of the fascinatingly subtle details of the series is that Gargantua and Pantagruel aren't introduced to us as giants. That is a revelation meant to dawn on us after reading about the umpteenth time they drowned their enemies in piss. Or by looking at the pictures. In fact, there are many subtleties hidden here and there throughout the series, and its satirical nature allows the author, Francois Rabelais (who published his first book under the anagrammatic pen name Alcofribas Nasier) to comment on the overly superstitious and eminently dysfunctional society in which he lived. He also has fun as a narrator, missing an entire battle because he was exploring the inside of Pantagruel's mouth the whole time.

Wait, are we sure this isn't a Chuck Tingle book too?

Intertwined with his satirical observations about the corruption of the clergy and the general slack-jawed stupidity human beings are given to when someone hands them a sword are a number of clever little anecdotes about the side characters. In one of these, one of Pantagruel's friends, Epistemon, gets his head lopped off and then sewed back on. He farts himself awake and eagerly tells his companions all about his trip to hell, which is apparently not unlike Detroit. Rather than screaming in agony as they bathe in a lake of fire, the souls in hell just work shitty jobs for shitty pay. Forever.

Marina LOVES Harry Potter and really enjoyed poking fun with this article. At Pottermore, she is a Ravenclaw (Hogwarts), a Pukwudgie (Ilvermorny), and has a lovely, supple and flexible 14-inch pine-wood wand with a dragon heartstring core. Her Patronus is a swallow. Adam, meanwhile, is a Hufflepuff (Hogwarts), a Pukwudgie (Ilvermorny), and is packing a slightly springy 12 1/2" laurel wood wand with a dragon heartstring core. His Patronus is a black mamba because he's rad.

It's Spring Break! You know what that means: hot coeds getting loose on the beaches of Cancun and becoming imperiled in all classic beach slasher ways: man-eating shark, school of piranhas, James Franco with dreadlocks. There are so many films about vacations gone wrong, it's a chore to wonder if there's even such a thing as a movie vacation gone right. Amity Island and Camp Crystal Lake are out. So what does that leave? The ship from Wall-E? Hawaii with the Brady Bunch? A road trip with famous curmudgeon Chevy Chase? On this month's live podcast Jack O'Brien and the Cracked staff are joined by some special guest comedians to figure out what would be the best vacation to take in a fictional universe. Tickets are $7 and can be purchased here!

Also check out 6 Terrifying Children's Cartoons From Around The World and The 5 Most Excessively Creepy Children's Educational Videos.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel, and check out 9 Horrifying Characters Aimed At Children, and other videos you won't see on the site!

Follow us on Facebook, and we'll follow you everywhere.