7 Of Your Dumb Fears (Science Says Are Justified)

Most people have an irrational fear of something or another, be it clowns, spiders, or being in a high place while surrounded by spider-clowns. For a long time, the official explanation for these fears was "You're a big wuss and there's probably something wrong with you." But now, science finally has some real answers. And what do you know? It turns out that a lot of the time, being afraid of commonplace things isn't so irrational after all, when you consider that ...

Dolls Freak Us Out Because They Screw With Our Threat Response

Creepy-ass dolls are a staple of the horror genre, from the clown that comes to life in Poltergeist to Chucky's homicidal shenanigans. Even when they aren't sentient and/or have a knife in their stubby little hands, though, many people find dolls unsettling to be around (or see in commercials). That's because evolution designed our brains that way to keep us alive.

See, the human brain has no small amount of trouble keeping its shit together when it encounters something that looks like a real face but isn't. At first glance, we all have an automatic visceral reaction to anything that remotely resembles a Homo sapiens mug, which partially explains why the more neurotic among us see stuff like the Virgin Mary in a slice of toast or Benedict Cumberbatch staring at us in the bark of an old maple tree.

Uh, that last one may be just us.

It's important from an evolutionary perspective that we make connections like that. Obviously, the earlier you notice that competing caveman sneaking up on you with a stabbin' stick in hand, the better. It's probably safe to say that those who didn't have this trait died off rather quickly.

"Huh. That bush with the necklace made of ears keeps getting closer. It's probably nothing."

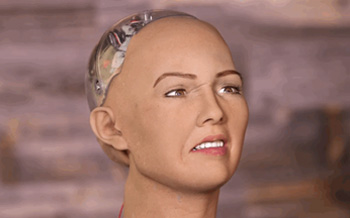

Pareidolia is the name for this reaction, and dolls play right into the instinctual jitters that ensue -- but only if they're fashioned with more skill than the average Amish pinecone-on-a-twig children's toy. Prior to the advent of realistic-looking dolls, pediophobia (the fear of dolls) wasn't really a thing, because the average children's toy was somewhere in between a dried apple doll and a bowel movement. But as dolls became more realistic -- and most notably, as robotic simulacrums have become way too lifelike for their own good -- the "Uncanny Valley" effect has been tweaking that primitive place inside our heads that tells us we should either immediately start running or scan the vicinity for a melting apparatus.

When will we learn what movies have taught us and start prosecuting technology like this as a war crime?

Clowns Are Scary Because We Know They're Up To No Good

As annoyingly moronic as the recent clown (non)epidemic was, the irrational fear of those who come in the night wearing red noses and unreasonably large shoes is a real thing. There's even a fancy term to describe it: "coulrophobia." But it's not the popular media portrayals (of clowns being murderous psychopaths bent on giggling dismemberment) that are evoking our fears. It's that they're scientifically ... wrong.

He's sad because you finally stopped screaming.

A British study from 2008 took a look at hospitals that had images of clowns plastered around their children's wards. You probably already know what they found out -- the kids considered this choice of decor somewhere near the opposite of comforting, and more like "frightening and unknowable." It's now believed that the reason youngsters (along with many fully grown adults) look at the average Bozo, Ronald, or Pennywise and experience an overwhelming sense of existential dread is that they automatically register in our brains as "troublesome."

Why? Well, while clowns aren't wearing masks, exactly, it's close enough. Our subconscious doesn't like that one little bit. And the stark, primary colors contrasting with one another on a human face simply ain't natural. Then there's the "fluidity" going on in those oversized clothes, plus their propensity for laughing too loudly for no good reason, and you've got plenty of ingredients for your brain to bake a "something is way, way fucking off" cake of terror.

"Corpse skin? Check. Alcoholic nose? Check. Mouth that looks like a lion after a kill? Check. Come on in, the birthday party's in the back yard."

Those factors may all seem rather obvious, but one thing you may not have thought about is how clowns, with their identities obscured by greasepaint, can short-circuit what our brains interpret as funny. Their entire shtick is intended to make people laugh, yet they are breaking all the codes of what polite society deems acceptable in order to do so, while committing acts that are almost invariably cruel, either to themselves or others. All while their true emotions are hidden away beneath the disguise. It's a conundrum that makes clowns such a natural fit for horror movies, and probably why so many of us feel a guttural revulsion toward Guy Fieri.

Spiders And Snakes Are Still Scary Because They Used To Kill Us On The Regular

We've made a living over the years reinforcing your instinctive dread of things that slither and skitter, but unless you have the misfortune of living in Australia or the Amazon (or count sticking your bare hand underneath random woodpiles as your inadvisable hobby of choice), there's no real reason to live in perpetual fear of arachnids or serpents. However, before there were things like houses, Winnebagos, and buckshot, way back when we were among nature's most vulnerable and squishy denizens, seeing one of them in the wild sure as hell was cause for alarm.

Zoologists have proven that the closer you get to the top of the food chain, the better your ability to grin like a smug son of a bitch.

We aren't born with an instinctive loathing of spiders and/or snakes; we just learn very fast how terrible they are, and not only because Jesus Christ look at them. Studies have shown that monkeys in a lab will learn to fear these creatures faster than rabbits, presumably because rabbits don't typically carry venom with them. Not only did natural selection clearly favor our ancestors with the sense to scamper away rapidly from anything with eight legs or none, but the very need to notice them may have contributed to our larger brain size and better vision. Knowing how to distinguish that reptile sneaking in a bush from something you can use to wipe your butt was essential to our evolution.

"Here lies Ogg, fond of roses. Picked this instead and died of necrosis."

To make absolutely sure all the evidence panned out, scientists used a tried-and-true method favored by mall Santas everywhere: scaring the shit out of toddlers. When a nervous group of three-year-olds were shown a series of photographs, even those who had no experience with reptiles were able to pick out snakes more readily than images of flowers, caterpillars, or frogs, and presumably a bit slower than 8x10 glossies of Steve Buscemi. And to be extra, extra sure, they performed a similar child-scarring experiment on some seven-month-olds. The conclusion was the same: Children instinctively associate snakes with fear, though probably not as much as they should associate men in lab coats with it.

One of many reasons Disney's Animal Kingdom no longer has the "Bin Full O' Boomslangs" attraction.

Our Aversion To Certain Foods Is Born In The Womb

Everyone has a certain food they just don't like, and sometimes, the loathing borders on the pathological. Maybe you cringe every time spinach even so much as touches the rest of your food. Or if you're powerful enough, you might go ahead and ban broccoli from Air Force One. It's a hatred that sometimes goes beyond a mere dislike of the taste, and it could go all the way back to when you were in utero.

There's an evolutionary component to why we favor certain foods over others. Sweet-tasting and fatty stuff means sugar and energy, so we prefer it over bitter things, which might indicate toxicity. As we get older, our tastes get a little more sophisticated, but many of the preferences that stick with us over our lifetimes developed back when we were a fetus, slurping down the amniotic fluid that held traces of whatever our mother's dietary habits happened to be. In other words, if your mom wouldn't touch a certain food with a 10-foot pole while pregnant, it will probably taste foreign and unpleasant to you once you come shooting out of her body.

"I LEARNED IT BY WATCHING BEING INSIDE OF YOU!"

In fact, it's been found that if a baby isn't exposed to a flavor during its first two years (including the time spent in the womb), they're much more likely to hate it for the rest of their lives. Flavor aversions can be altered, however, if you're willing to put some work into it. Studies have shown if you force exposure to something "yucky" around 10-15 times, eventually the aversion will be lessened, if not eliminated altogether. The research didn't mention how to deal with the ensuing grudge that may manifest itself once the infant becomes a teenager.

Things With Too Many Holes May Remind Us Of Deadly Beasts

Do English muffins raise your hackles? Does seeing honeycomb or coral put the hygienic integrity of your pants at risk? Then you might have something called trypophobia. It literally means "fear of holes," and is described as "a condition which triggers individuals to suffer an emotional reaction when viewing seemingly innocuous images of clusters of objects." While there's no proof yet that this condition is a real thing, many readers will take issue with that statement once they recover from the uncontrollable shakes brought on by images like this:

And if you count yourself as a member of the trypophobe community, you definitely shouldn't click on this.

It sounds silly on paper. Why the hell would anyone be afraid of holes, of all things? Because of what might be in them? Well, sort of. Similarly to the way sneaky critters give many of us the automatic willies, trypophobia might also have something to do with hazardous animals -- like the octopus. For real. These days, unless you're foolish enough to live on a houseboat in kraken territory, running across a deadly cephalopod during your everyday travels might seem rather unlikely. However, when ancient humans waded out into the surf to gather food, there were plenty of creatures (like the outrageously toxic blue-ringed octopus) that could stop their hearts well before they could stumble their hairy asses back to shore.

His neurotoxin can kill 26 adults in a few minutes, or Ozzy Osbourne over the course of several years.

Specifically, scientists found that people with trypophobia reacted most strongly to images containing a "high contrast at midrange spatial frequencies," which refers to the repetitive quality of certain features visible with a certain space. That's a complicated way of putting things, but this might put it into perspective: You know what else has "high contrast at midrange spatial frequencies," aside from those aforementioned octopuses? King cobras, for starters. Also a festively named murder scorpion called the deathstalker. So yeah, don't be too hard on yourself if you can't help but flail your arms about whenever someone dangles a slice of Swiss cheese in front of your face. It might mean your ancestors merely had the good sense to wait for somebody else to be the very first live scorpion taste-tester.

We had to go through a lot of trial and error before discovering cocaine.

The Word "Moist" May Trigger Our Disgust Mechanism

We all have particular words that annoy us, like "methinks," "fleek," or "LaBeouf." Sometimes, though, words can evoke a physical, visceral response in the listener even without the aid of audiovisual cues provided by Michael Bay. The phenomenon is known as "word aversion," and for some reason, the one word that seems to drive the most people bonkers is "moist."

So why do people find the word "moist" so revolting? Participants in a study claimed it was because of how the word sounds, rather than any association one might make with summertime underwear woes or finding a used hankie in their soup. This gels with the theory that word aversion has something to do with synesthesia, a phenomenon wherein certain combinations of sounds or musical tones can sometimes cause the listener to recoil in nauseated horror.

A technique perfected by 97 out of 100 college students who play their guitar in public.

And yet, it might be less complicated than that. The moist-haters in the study above didn't have any problems with similar-sounding words, but they were more likely to be repelled by ones like "phlegm" and "puke" than the rest of us. The researchers concluded that they're disgusted by "moist" because they strongly associate it with bodily fluids, unlike others who use the word to describe cake or in the latest chapter of their erotic Dragon Ball Z fanfic.

The truth is that we may never know all the factors that make "moist" the Simon Cowell of words. Or as one linguist suggests, the fact that people have been constantly harping on it for years may have turned it into the one thing that might be even worse than the word itself: a meme.

We Hate Nails On A Chalkboard Because Of The Shape Of Our Ears

You'll find few individuals who don't wish to seek furious violence upon those dark souls who, for no other reason than to be a titanic shitbird, scrape their fingernails across a chalkboard. Styrofoam and balloon squeaks are right up there on the list of the world's most aggravating noises ... but why do we find the racket these particular things make so intensely horrible?

Scientists have actually pinpointed the range in which we find sounds particularly painful: 2,000-4,000 Hertz (no pun intended). Silverware scraping across a plate falls within this range, and the reason that and the aforementioned activities affect us the way they do may point out a vulnerability in the way the human ear is built. The shape of our ear canals amplify things within this range especially, and one of the only upsides of getting your ears blown out by loud noises is that the ability to hear these sounds will be one of the first things to go.

"I had to give up playing heavy metal guitar, but on the bright side, I've been employee of the month at the balloon animal factory five times running."

The effects aren't only psychological -- 2kHz-4kHz scrapes and squeaks can physically cause our blood pressure and heart rate to shoot up as well. Why the hell would our bodies do that us? Well, it's thought that this reaction may have evolved to put us on special alert for sounds like a baby crying or someone screaming for help. Researchers are hoping to use what they've learned to assist people who make appliances like vacuum cleaners and such less annoying. Apart from how nice that would be for us, we know a few family dogs that would certainly be grateful for an innovation like that as well.

Hoover could hire Sarah McLachlan as a spokesperson, and everybody would make a bundle.

You can pre-order E. Reid Ross' new book on Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

2016 is almost over. Yes the endless, rotten shit hurricane of a year which took away Bowie, Prince and Florence Henderson and gave us Trump, Harambe and the Zika virus is finally drawing to a close. So, to give this bitch a proper viking funeral, Jack O'Brien and the crew, which includes Dan O'Brien, Alex Schmidt, and comedian Caitlin Gill, are going to send out 2016 with Cracked's year in review in review. They'll rectify where every other year-in-review goes wrong by giving some much needed airtime to the positive stories from the 2016 and shedding light on the year's most important stories that got overlooked. Get your tickets here.

Also check out 6 Freaky Things Your Body Does (Explained By Science) and 5 Weirdly Satisfying Scientific Explanations For Superpowers.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel, and check out 4 Obnoxious Old People Behaviors (Explained By Science) and other videos you won't see on the site!

Follow us on Facebook, and let's be best friends forever.