The 6 Most Nightmarish Worms on the Planet

You probably think you know everything you need to about worms. They're just wiggling tubes of flesh with indistinguishable asses and faces that commit suicide on sidewalks during rainstorms. All caught up. But the benign worms you're used to seeing speared on fishhooks and fried up in children's literature are only a tiny percent of all the species of worm out there. And when we say "out there," we mean "crawling free of the bowels of hell as we speak."

Bobbit Worm

At over 10 feet long, bobbit worms are about the closest thing we have to the sand worm in Dune. They have toxic bristles up and down their body that can cause permanent nerve damage to anyone who touches them, and they feed by grabbing their prey with massive, strong jaws and sucking it down into the sand.

They are ambush predators that wait in shallow waters with only about a tenth of their body poking out of the sand and their mouths stretched completely open. As soon as one of their antennae detects something in the water, they lunge for it, even if it's significantly bigger than they are. Their strikes, it should be noted, are so powerful that they'll sometimes accidentally just cut fish in half while trying to grab them. So don't be fooled by the fact that, up close, it's the iridescent color of a middle school girl's Trapper Keeper.

Dante's Inferno would have been so much scarier if he'd known anything about the ocean.

To get a sense of how horrifying these worms are, at Newquay's Blue Reef Aquarium in the U.K., they couldn't figure out what was eating all their fish each night. They set up traps with fishing line and hooks, and each morning the lines were snapped and the hooks and bait were gone. After taking the aquarium apart, they found a massive bobbit worm in the sand that had apparently just been digesting the hooks.

Oh, and the bobbit worm, just like us, prefers warm, shallow waters. So we're probably going to have to let them have the good beaches for now.

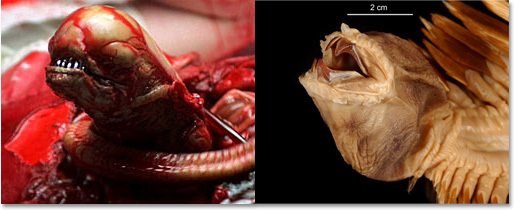

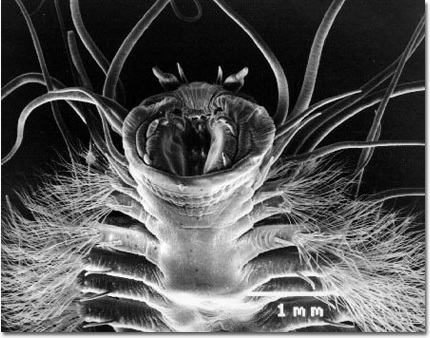

Ragworms

As you can see, the ragworm has an earwig's ass for a face. Those pincers right around its face hole are extraordinarily strong, too -- they can provide a nasty bite when the ragworm is threatened because the mandibles are made out of a unique substance that's both harder and lighter than most synthetic material we have. As a result, scientists have been ecstatically tearing the jaws off these worms so they can get them under a microscope and hopefully replicate it.

But as a non-scientist, this worm is all downsides for you. Think of all your least favorite characteristics of insects, spiders and worms, then combine them all together. It has the body of a centipede divided up into about 120 segments, each with its own set of appendages to help it swim or writhe around on land. It lives in slime-lined holes in shallow waters and spins a sticky web of mucus over the entrance like some kind of mutated snot spider.

"Anybody got a tissue ... or a flamethrower?"

Unlike spiders, though, who have to hang around until something's dumb enough to fly into their webs, ragworms undulate around in just the right way to create currents in the water near their trap. Any prey unlucky enough to get caught in those currents is helplessly drawn into the web, and then the ragworm just consumes the whole thing, snot web and all, because, and we can't stress this enough, it's just awful. Here's another look at its face:

Play this in the background for full effect.

Just ... wow. To the ragworm's credit, that view is more hilarious than terrifying. It looks like it just wriggled out of Jim Henson's imagination. It also has that shocked expression that says it's as surprised as anyone that it's been allowed to live this long. Oh, and did we mention they can get up to 3 feet long? So keep that in mind the next time everybody wants to go skinny dipping off the banks of some dark body of water.

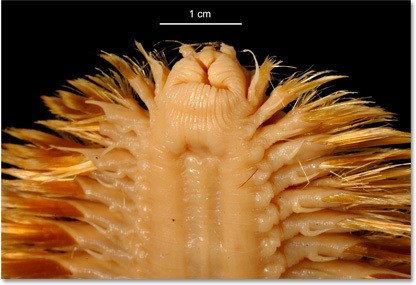

Eulagisca gigantea

If you're not sure what you're looking at there, let's back up. At first glance, Eulagisca gigantea doesn't seem that threatening. It is only about 8 inches long, lives far off in the waters of Antarctica and looks vaguely like it could stand in for a dustpan broom in a pinch.

If ALF used condoms, they'd look sort of like this.

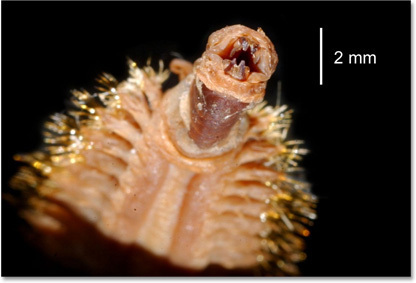

Aside from that creepy, sunken head, you might almost be tempted to run your fingers through its bristles. But just be aware that there is no guarantee you would get all your fingers back. Let us show you why:

It's basically a Swiffer designed by H.P. Lovecraft.

Surprise! That sunken head in the first photo is actually a whole retractable mouth with fangs. So aside from looking like a face-hugger with little blond ponytails instead of tentacles, E. gigantea also has the deflated head of a chest-burster.

"Hello, we'll be in your nightmares this evening."

Additionally, the worms have full body armor. They have tiny protective scales across their entire midsection designed to keep them safe from their main threats, which presumably are people in exosuits looking to make a name for themselves. Scientists still don't know much about their diets or how they breed, partially because they live deep in the oceans of Antarctica, and partially because why would anyone get to know something they're already certain they hate?

Velvet Worms

If the above looks to you like a worm squirting out twin streams of snot many times the length of its body, well, you have good eyes.

The velvet worm doesn't have retractable fangs, isn't the size of a deadly snake and doesn't hide in the sand. It's just a small, slow, soft-skinned hunk of meat that hangs out in trees. In fact, even though it has little stubby legs, it has no joints and can't move much faster than a snail. But it's also a predator. In that respect, being eaten by a velvet worm is a lot like being eaten by a zombie: Its slow, lumbering pace actually makes it even more horrifying than any of the other worms on this list.

When the velvet worm finds prey it wants to eat, it rears up the front half of its body and fires that sticky webbing to immobilize it, like a terrible Spider-Man.

You do not want to see this thing make out with Kirsten Dunst in the rain.

Actually, it's more of a mucus than a webbing, so it's actually more like a person who is perpetually sick, trapping victims in his snot. They're such proficient hunters that they can trap large beetles and even deadly funnel spiders. They also look completely absurd:

Once the prey is glued to a branch, it can only watch helplessly as the velvet worm slowly shambles over and feels around the body of the insect for a soft spot in the armor of the exoskeleton. When it finds that spot, it pries away a chunk of the outer layer with its terrible, terrible mouth.

What pinatas look like in hell.

Then the velvet worm will spit saliva inside the prey and let it stew inside the shell while the insect is still alive, essentially digesting the bug before eating it. Finally, when everything has been dissolved into a soupy mess, it sucks it all back out, leaving the glued exoskeleton where it stands. So while those children in Honey, I Shrunk the Kids were freaked out when they encountered an ant, had they come across a velvet worm, it likely would have shot a snot rocket at them and then used their own bodies as crock pots. But yeah, ants are scary, sure.

Methane Ice Worm

We're honestly not sure if that's its ass or its mouth.

At the very bottom of the ocean, there are cracks in the sea floor through which methane spews out of the torture chamber in the middle of the earth, a phenomenon that scientists refer to as "hell's farts" (or they should, at least). Here, where the ocean water is near freezing, where the pressure is intense enough to crush your bones and where the stench of methane coats everything, lives that ridiculous thing you see above.

Methane turns into a solid at warmer temperatures than water, so technically these bristly, tentacled monstrosities live in pockets of methane ice. Unfortunately, we don't know much else about these worms, since we didn't even realize they existed until 1997, presumably because scientists were dragging their feet about having to look for life at the threshold to Hades.

"Yeah, I've got a non-mentally scarring thing this weekend. Sorry."

But since we don't have a formal rule for science stating that we shouldn't touch anything that has both hair and tentacles (yet), scientists are now keeping colonies of these worms in labs. From what they've discovered, the methane ice worms use those hair appendages or fur fingers to swim around on fart ice while whipping those freakish tentacles around to find bacteria they can suck into their gaping maws.

"Hi there! I crawl through your various holes at night while you sleep."

Science is excited about this species because of the implications it has for extraterrestrial life. The fact that an animal can actually live and thrive in such extreme conditions means that there's a better chance of finding life on moons and planets that are just silly with methane. Hey, maybe when it's time to explore those planets ourselves, we can just collect a bunch of these worms from the ocean and send them out there. Sure, we'd need to make them bigger first, and super intelligent, but that's what mad scientists are for.

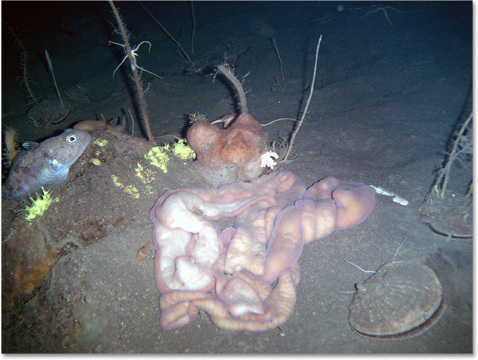

Antarctic Proboscis Worms (Nemertean Worms)

What very clearly looks like someone's large intestine that sunk to the bottom of the ocean is actually a predator and scavenger worm that can reach lengths of around six and a half feet.

Deep beneath the ice in the waters of Antarctica, this worm will eat anything dead it can find, and barring a carcass, it will kill its own food. It has a proboscis, but not the fragile little one you'd think of on the face of a butterfly. This proboscis is more like a really sharp hammer. The worm will stab its prey over and over again with its own face until the prey stops moving. Then it gets really disgusting.

Is that a side mouth?

The proboscis worm doesn't really have teeth for chewing, so it prefers the softest tissue of an animal, essentially eating its prey from the inside out. It will just poke a hole in the skin and go to town on the guts. And because they're scavengers as well, the other worms will notice the meal and wind themselves around it too until there's just a revolting knot of massive tongues all trying to lick the insides of some dead thing. Here's a video of them eating a seal by climbing through its eyes.

Thus marks the first time we wished David Attenborough would stop talking about nature.

If you're wondering how something so awful could be allowed to get so big, proboscis worms don't have any natural predators, primarily because they can secrete acid from their skin. If they ever feel threatened, they release a strong acid into the water around them that can kill any fish that's stupid enough to try to eat one of these pieces of nightmare spaghetti.

"But what's their weakness?!" you cry, distraught that your planned Antarctic snorkeling trip has hit a snag. Well, we're sorry to say that they don't really have one. If they get into a bind, they can even shape-change. Badass as they are, they're also ridiculously flexible, even by worm standards. For example, since they breathe through their skin, if oxygen levels in the water start dropping, they'll just flatten themselves out like pizza dough, giving them more surface area to breathe with and less distance for oxygen to travel. They are perfectly adapted for their environment, and while they may not be able to kill an experienced arctic diver like yourself, they will certainly be hoping you stop moving long enough for them to crawl through your orifices and eat your insides.

If your dreams aren't jam-packed enough with terror, then feel free to learn about 12 Things You'll Wish You'd Never Seen Under a Microscope and 8 Terrifying Skeletons of Adorable Animals.