7 Bizarre Prehistoric Versions of Modern-Day Animals

Nobody ever cranks out a masterpiece in one sitting. Not even Mother Nature gets it right the first time. If she did, then the prehistoric ages wouldn't have been filled with stupid and bizarre-looking prototypes of modern species that seemed doomed to fail from the start. Some of evolution's laughable early drafts include ...

Platybelodons, aka Elephants With Giant Trunk-Mouths

Who knew that the quickest way to strip an elephant of all its majesty was to replace that dick it carries around on its face with a duck bill? About 10 million years ago, back when evolution was still throwing everything at the wall to see what stuck, there were actually several different trial-and-error elephants wandering around. But Platybelodon was the only one with a long rat tail and a dustpan for a mouth.

Paleontologists apparently have long-winded arguments on why nature would intentionally make an animal look like that. Some suspect that the shovel tusk was useful for gobbling up aquatic vegetation, but others are adamant that Platybelodon grabbed onto tree branches with its mouth and then sawed into them with those hillbilly teeth on the bottom. But regardless of the actual function, Platybelodon seems to have sacrificed all aesthetic to achieve it, because these elephants are an embarrassment.

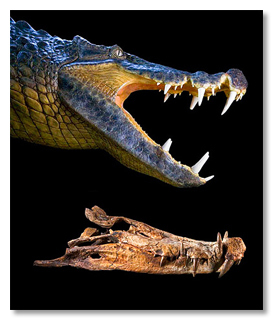

This comparison, showing its jawbone, illustrates just how well it could keep snow off of its driveway.

The shortened tusks aren't doing it any favors either. It's the one menacing weapon modern elephants have, and nature decided, "What if I try making them so short that they're completely useless and then use them as decoration on either side of a permanent guffaw?" The only reason these animals lived as long as they did was because predators could only laugh and move on in search of something less absurd to eat.

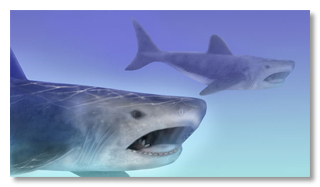

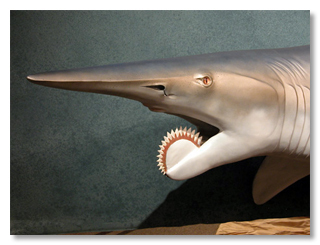

Helicoprion, aka the WTF-Mouthed Shark

Helicoprion is essentially a shark from 250 million years ago with a buzz saw for a lower jaw. If you're having a hard time wrapping your head around the logistics of that, then congratulations, you and science are in the same boat. Unfortunately, since a shark's skeletal structure is made almost exclusively of cartilage, no one has ever found more significant remains of the Helicoprion than these serrated jaws that look like they were pulled from a Tim Burton set. In fact, paleontologists originally thought the Helicoprion mouth they discovered was just an ammonite. It wasn't until later on that researchers realized that what they had found was an important example of Mother Nature testing the boundaries of the crazy shit she could get away with.

Paleontologists are still trying to figure out how this shark even fed itself with such an absurd mouth. The leading theory is that Helicoprion would have used its flexible jaw like a whip, lashing what was essentially a spiked tentacle into schools of fish and then pulling in whatever it managed to stab. But experts can't even agree on where Helicoprion would have stored its lower jaw when it wasn't using it to devastate swarms of prehistoric fish -- that's why different artists' renditions don't even look like the same animal:

"We're just pretty much guessing here."

"Oh yeah? Well, we can guess much stupider than you."

Originally they assumed that the teeth just rolled back under the jaw, but the most recent hypothesis is that the shark would keep them tucked neatly away in its throat, because obviously that's always the best place to keep a deadly coil of razors.

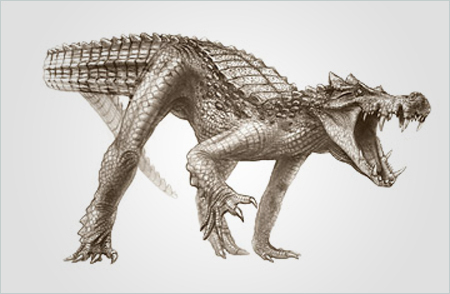

Kaprosuchus saharicus, aka Long-Legged Crocodiles

Anyone who's watched more than two hours of the Discovery Channel knows that crocodiles are sharp-toothed, armored, writhing instruments of death ... but only if they're in about five feet of water. Ten feet farther on shore and suddenly they're 800 pounds of slow-moving, useless leather with sharp teeth at one end. If nothing else, the fact that crocodiles can't and probably won't chase you on land is the most comforting characteristic of what would otherwise be a relentless murder machine.

Except that about 100 million years ago, that wasn't the case. Kaprosuchus saharicus was evolution's stab at giving one predator every advantage except the ability to fly, making it completely unbeatable. Paleontologists often casually talk about them galloping after dinosaurs on their long legs like that's just a thing crocodiles do regularly. In fact, while the non-scientific name for them is "BoarCroc," they've also earned the adorable nickname "dinosaur slicer."

We like to think of them more as "hell fillers."

It's honestly surprising that anything else could survive with these wingless dragons sprinting around and eating everything. When the Earth hit the reset button with the Ice Age, we're fairly confident that one of the first changes on the list for new species was to give the crocodile at least one weakness.

Synthetoceras, aka Horned Horses

Given that Synthetoceras roamed around the grasslands of what's now Texas, it's a little infuriating to know that evolution zigged when it could have zagged, giving us boring old horses as the most iconic animals of the Old West when we could have had this ancient species with a slingshot mounted on its face. Even though it's most closely related to the camel, there's no reason to think that humanity couldn't have domesticated a few of these. Now try to imagine American history with cowboys riding Synthetoceras into the sunset, or Native Americans steadying their rifles in that little notch while charging at circled pioneer wagons.

Granted, Synthetoceras looks like it was invented by a child in a desperate attempt to make his love of unicorns more macho. But surely there must have been an evolutionary benefit to having a permanent antler on the front of the Synthetoceras' face. The going theory among experts is that they used them for sparring with one another, which is completely boring. We'll go on believing that they used their face horns as fancy little forks for feeding one another, thank you.

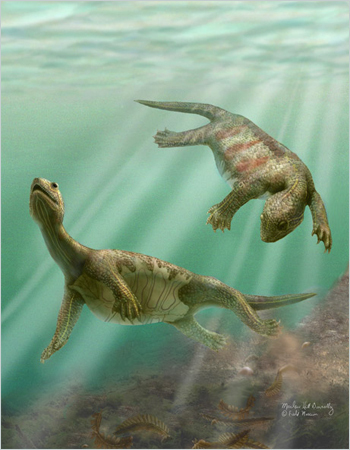

Odontochelys semitestacea, aka Shell-Less Turtles

Evolution is lazy. It takes thousands of years to produce one minor change, and even then it will do the absolute bare minimum. Point in case, Odontochelys semitestacea. About 220 million years ago, turtles were essentially just drifting hunks of meat for predators. Finally, evolution stepped in and decided that it was only fair to give the turtles some kind of natural defense. The result? A hard belly, and that's it.

Odontochelys semitestacea was usually snapped up by whatever sea monsters lived in deep waters. Because the predators attacked from the bottom, the turtles that developed shells on their stomachs survived longer. The only problem was that as soon as anything figured out how to attack from the top or even bothered to flip one of these turtles around, suddenly it was the equivalent of putting a meal on a plate. If anything, the evolutionary advancement of Odontochelys semitestacea just made for fancier predators.

"At least my horrible death was convenient."

Still, the fossil of Odontochelys semitestacea has helped paleontologists determine how turtles actually evolved their full shells. What they originally assumed was a thicker skin that evolved into a hard casing now looks more like extensions of the backbone and ribs that grew together over time to make a shell. But regardless of how important the discovery of this species might be, it still looks just like a naked turtle to us. One that's gone skinny dipping in some ancient pool, with its shell up on the shore.

Odobenocetops, aka Walrus-Face Whale

Even though Mother Nature usually fusses with the attributes of each type of animal separately, she isn't above mashing two totally different species together just to see what happens. Sometimes the outcome is amazing, combining all the best characteristics of both, and other times the final product is Odobenocetops, aka the failed mix tape of the ocean.

During the Pliocene period about 3.5 million years ago, Odobenocetops was essentially a whale with the head of a walrus, except one tusk was much longer than the other and its face was locked in a perpetual Eeyore sulk. The longer tusk could grow to be about 3 feet long, but it was completely useless for defending Odobenocetops against predators because it was too brittle. In fact, no one really knows why it had such ridiculously mismatched and ineffectual fangs.

"I may look retarded, but I get better reception than your cellphone."

We can't overstate how harmless and unprepared these walrus/whales were for the prehistoric world they lived in. To give you some context, they were around during the same era as the megalodon shark, an apex predator roughly the size of a blue whale, with five rows of teeth stretched across a 7-foot jaw. While it was technically carnivorous, Odobenocetops only ate clams and worms that it sucked up from the sand, and presumably it complained all the time about how nobody ever remembered to invite it to their birthday parties. That sad pout on its face almost makes it look like Odobenocetops knew just how ridiculous it was.

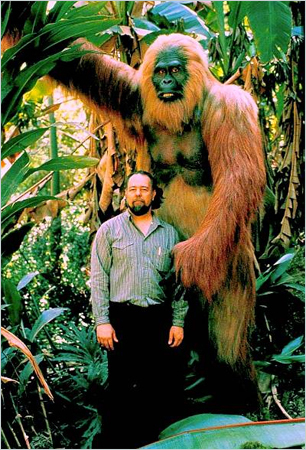

Gigantopithecus, aka Sasquatch

It seems unfair that while there are a handful of wildly different prehistoric versions of most species, the biggest variation among human ancestors was the slope of their foreheads. Sadly, evolution never experimented much with giving primates hooves or poisonous skin, so compared to nearly every other animal, our physical variances seem pretty lame.

Or at least they did until the 1930s, when a paleoanthropologist discovered the teeth of a primate that was over 10 feet tall and weighed around 1,200 pounds. For some context, a male silverback gorilla weighs about 400 pounds. Gigantopithecus was bigger than a polar bear and looked suspiciously like Bigfoot if he was making a considerable effort not to be shot during buck-hunting season.

And if you're friendly enough to him, he'll protect your rebel ass on Hoth.

The giant ape lived in the jungles of Southeast Asia, where it survived exclusively on plants and fruits, judging by the shape of its teeth. As horrifying as it might be to meet one of these monsters in the forest, there's a pretty good chance that our ancestors did occasionally. Gigantopithecus and early man were alive at the same time and lived in the same areas. In fact, humanity might be at least partially responsible for their extinction. Yeah, some things never change.

Agneeth has recently decided that he really needs to start being consistent with his guitar practice schedule, so you can see his progress here.

For more animals that don't look quite right, check out 15 Animals You Won't Believe Aren't Photoshopped and 8 Terrifying Skeletons of Adorable Animals.

If you're pressed for time and just looking for a quick fix, then check out 5 Bizarrely Specific Subgenres of Horror Movies.