6 Books Everyone (Including Your English Teacher) Got Wrong

With most every classic novel comes some outlandish interpretations. Some people have wild fringe theories about Harry Potter as an allegory for young gay love and Lord of the Rings being about WWII and the atom bomb. But some of these laughably wrong interpretations stick. In fact, you were taught some of them in school ...

Upton Sinclair's The Jungle

Upton Sinclair's expose of the American meatpacking industry is largely to thank for the massive drop in cases of gastroenteritis (and rise of vegetarianism) around the dawn of the 20th century. When the book was published, the public, pretty keen on taking solid shits, was outraged by the novel's accurate depictions of the unsanitary conditions in slaughterhouses and lack of regulations forbidding the practice of shoveling week-old entrails off the floor along with the cow shit and calling it sausage.

President Teddy Roosevelt took action as a result, leading to the Pure Food and Drug Act, the Meat Inspection Act and eventually the FDA, despite getting his meat primarily from large game he beat to death with a club (probably).

"Who's hungry?"

What it's really about:

It wasn't about sanitation or meat safety. Sinclair was actually trying to expose the exploitation of American factory workers and convert Americans to socialism.

He went undercover for several weeks as a meat packer and not only saw that working conditions in meat-packing factories at the time were horribly unsafe, but that there was massive corruption within the upper levels of management. The stockyards exploited not only the common man, but also the common women and children, who worked the same lengthy shifts and lost the same useful appendages to machinery without proper safeguards. At one point in the book, an employee accidentally falls inside a giant meat grinder and is later sold as lard.

A pinch of Mitch in every bite.

But much to Sinclair's frustration, the public's reaction was less "that poor exploited worker!" and more "HOLY SHIT THERE MIGHT BE PEOPLE IN MY LARD." They read right past the hardship of the workers and focused entirely on how gross the meat-packing process was.

Adding insult to injury, the passing of the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act meant that taxpayers, not the meatpackers, were responsible for the $30 million a year costs of inspection, giving Sinclair further shit to gripe about as it added even more burden to the American worker.

"We have to wear coats now?"

It didn't help that Roosevelt didn't sympathize with Sinclair's socialist views, calling him a crackpot and stating that three-fourths of his book was the same bullshit everyone was apparently eating at the time. Sinclair would later take matters into his own hands, running for Congress twice on the Socialist ticket. He lost. Hell, he should have just run on the "No more shit in your hamburger" ticket. That seems like a pretty easy win right there.

Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451

It's the defining anti-censorship book of our time. The image of government crews gathering up and burning books is as iconic in the free world as Big Brother.

In Fahrenheit 451, America in the future is a clusterfucked society and a nation of dimwits. Books are outlawed for promoting intellectualism and free thinking, which inevitably leads to objective discourse and debate, which are now considered politically incorrect because dissenting opinions make people sad. Instead of preventing homes from going up in flames, firemen have been reassigned to rifle through homes and seize any contraband books that remain.

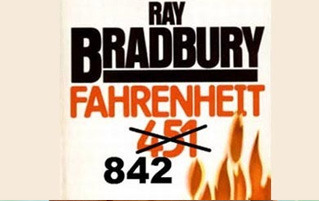

Just about every critic and literary scholar on the planet viewed the novel as metaphor for the dangers of state-sponsored censorship. Can't see this as much of a stretch, considering it was about book burning (although, the title may have suggested that it was really about book warming, since, according to Bradbury's sources, the temperature at which paper combusts is actually 450 degrees Celsius, or 842 degrees Fahrenheit).

This didn't occur to him?

What it's really about:

Bradbury was actually more concerned with TV destroying interest in literature than he was with government censorship and officials running around libraries with lit matches. According to Bradbury, television is useless and compresses important information about the world into little factoids, contributing to society's ever-shrinking attention span. Like "Video Killed the Radio Star," television would kill the, uh, book star (he said same thing about radio too, by the way). An interesting rant from the author, considering that much of Bradbury's fame was a direct result of his stories being portrayed on science fiction shows.

Also,

"Featuring your host, a Martian-ophilic hypocrite."

For a science fiction writer who predicted the development of flat-screen TVs you hang on the wall, ATMs and virtual reality, he sure hates new technology. Along with bitching about radio and television, Bradbury also has something against the Internet. He apparently told Yahoo! they could go fuck themselves, and as far as he's concerned, the Internet can go to hell. He doesn't own a computer, needless to say. At least we can say whatever we want about him without getting sued.

What probably pissed Bradbury off more than anything was that people completely disregarded his interpretation of his own book. In fact, when Bradbury was a guest lecturer in a class at UCLA, students flat-out told him to his face that he was mistaken and that his book is really about censorship. He walked out.

Later, he accused the camera of stealing his soul.

Machiavelli's The Prince

If you've ever heard a politician or other powerful person referred to as "Machiavellian," you can guess it's not a compliment. That's thanks to a shifty-looking Italian diplomat named Machiavelli. He was bad enough that we turned his name into a pejorative adjective that means "cruel, amoral tyrant." Napoleon, Stalin and Mussolini were three of his biggest fans, and the Mafia considers Machiavelli the father of the organization.

In his defense, he cleans up well.

The reason for this is Machiavelli's The Prince, one of the most notorious political treatises ever written, designed as an instruction manual for the Florentine dictator Lorenzo de' Medici to help him be more of a bastard. Completely disregarding moral concerns in politics, the book serves as a levelheaded discourse on the best way to assert and maintain power, noting that it's better to be feared than loved, and that dishonesty pays off in the long run as long as you lie about how dishonest you are.

Machiavelli's masterpiece is equal parts brilliant and irresponsible, showing tyrants how best to run a country like a video game.

What it's really about:

Actually, Machiavelli was totally just trolling. Far from being the spiritual patriarch of the Gambino crime family, he was a renowned proponent of free republics, as noted in a few obscure texts called everything else he ever wrote. The reason The Prince endured the ages while the rest of his philosophy gathered dust in the back of an old library warehouse is chiefly 1) it's really short, and 2) it angries up the blood. By far the best way to get a book on the best-seller list is to write something that pisses everyone off, but the drawback is that it steamrolls the message of any work that's only meant to be understood in context.

The context in this case is that the Medici family to whom he dedicated his love letter is the same group who personally broke Machiavelli's arms for being such a staunch advocate for free government. He worked for the Florentine Republic before the Medicis marched in, mowed down the government and mercilessly tortured him, and then he sat down and wrote The Prince from his shack in exile, assumedly with some really bendy handwriting (on account of the arms). When you learn about that, it kind of adds a new layer of meaning to the text -- it suddenly sounds like it's dripping with sarcasm.

Not everyone was in on the joke.

For centuries, the consensus on Machiavelli's best-known work has been that he was just trying to brown-nose his way back into the government. But a deeper study of his full body of work reveals that this is a pretty absurd ambition, considering not only did Machiavelli repeatedly say that "popular rule is always better than the rule of princes," but after he wrote The Prince, he went right on back to writing treatises about the awesomeness of republics. Considering also that he was no stranger to the literary art of satire, scholars these days are turning to a more likely scenario -- Machiavelli was the Stephen Colbert of the Renaissance.

Part of the blame might also be leveled at the shitty job that people have done in trying to translate his work into English. It's from Machiavelli that we get the notorious phrase "the end justifies the means." A much more accurate translation from the original Italian is something more like "one must consider the end," which kind of means something totally different.

At least he got a badass statue.

Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

Anybody who grew up in the 1960s (and still remembers anything about it) can tell you what Lewis Carroll's classic children's book was really all about: A girl takes a "trip" down the rabbit hole and finds herself in a surreal world where animals start talking to her. After she eats some "mushrooms," everything starts to change sizes before her eyes. She meets an over-stimulated "white rabbit" and a stoned caterpillar smoking a "shitload of drugs."

We didn't really need Jefferson Airplane to clarify it; Alice in Wonderland is the Fear and Loathing of fairy tales. It became one of the most important allegories of the 60s counterculture, with scenes that accurately correspond to the sensation of every mind-altering substance known to man. The Beatles drew heavily from Carroll's work during their fucked-up phase (1962-1971, according to historians), and acid still comes in tabs with the Cheshire Cat printed on them.

What it's really about:

Lewis Carroll was the pen name of the very conservative Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, Anglican deacon and professor of mathematics. He wrote Alice in the 1860s, a time when the most radical thing taking place on college campuses was complex math. While that sounds innocent enough, Carroll thought it would lead straight to Satan. Yes, the book that launched a million acid trips was written by the biggest square in the universe for the nerdiest reason imaginable.

NERD.

All the weird drug-trippy stuff that's been misinterpreted since Woodstock is, we're sorry to say, really just an elaborate satire of modern mathematics. Dodgson was old school when it came to math, because right up until his time, math professors still taught from a 2,000-year-old textbook. That all began to change in the mid-1800s, when a bunch of irritating young people invaded academia and started bringing new concepts to math. Weird new concepts. Like "imaginary numbers" and other crazy stuff.

What incensed Dodgson was that math no longer had any real-world grounding. He knew that you could add two apples to three apples to get five apples, but once you start thinking about the square root of -1 apples, you're living on the moon. The Rev. Dodgson thought the new mathematics was completely absurd, like something you'd dream up if you were on drugs.

Dodgson to new mathematics: "Get the hell off my lawn."

So he decided to write a book about a world that followed the laws of abstract mathematics, purely to point out the batshit lunacy of it. Things keep changing size and proportion before Alice's eyes, not because she's tripping on bad acid, but because the world is based on stupid postmodern algebra with shit like imaginary numbers that don't even make any sense god dammit. "Alice" was the sensible Euclidian mathematician trying desperately to keep herself sane and tempered, while "Wonderland" was really Christ Church College at Oxford, where Dodgson worked, and its inhabitants were just as barking mad as he thought his colleagues really were.

Jack Kerouac's On the Road

Before there were hippies, there were beatniks: the goateed hipsters in berets and black turtlenecks, playing the bongos and writing shitty poetry. During the late 50s, these pseudo-intellectuals crowded every coffee house and jazz club with an open mic night.

Jack Kerouac is responsible for every last one of them. His semiautobiographical novel, On the Road, made being a nonconformist trendy and inspired an entire movement he coined "The Beat Generation."

Crazy, baby.

The book is about Kerouac's bromance with a former car thief with a knack for free verse, and chronicles their adventures across America, as they abandon square social expectations for a more hedonistic lifestyle filled with sex, drugs and jazz. It wasn't just a beatnik bible, either. Major counterculture icons of the 60s, like Jim Morrison and Bob Dylan, were said to have "dug it." In fact, it's generally believed that hippies are really just beatniks with worse hygiene.

And worse taste in fashion.

What it's really about:

First of all, Kerouac hated beatniks; he thought they were a bunch of posers. Anyone who wanted to be a part of "The Beat Generation" completely missed the point. In his mind, those who were "Beat" were beaten down by society's demands and struggled to find their place in the world. It was not something you chose to be because it would help you meet chicks.

As far as his time On the Road, he hated that too. Kerouac spent roughly seven years roaming the countryside looking for answers. He never found any, and it's pretty clear in the book. Yes, there were some wild times that seemed like a blast, but it got old after awhile. Nevertheless, it was that side of his character everyone celebrated even though he tried to put it behind him.

Kerouac was a Catholic who grew to have pretty conservative politics, so he was always resentful of inspiring what would become a cultural revolution. And keep in mind, Kerouac wasn't even describing events that took place during that time. Since the novel came out in the late 50s, everyone assumed he was describing the thought and feelings of that era, but the events of the novel took place almost a decade before. He wasn't even writing about the era he supposedly defined.

Friedrich Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra

Friedrich Nietzsche is probably the most-recognized name in philosophy behind Socrates and Aristotle. But his notoriety with the layman is mainly due to the people he inspired -- Ted Bundy, Mussolini and Hitler. His seminal work, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, is about as cheery as anything Nietzsche ever penned. It popularized the quote "God is dead" and illustrates Nietzsche's disdain for the concept of traditional morality and his prediction that some kind of master race would soon drag itself out of the slime and rule the world.

He refers to the rightful owner of the world as the "superman" and the "splendid blond beast," and anyone with a passing interest in modern history knows exactly where that line of thinking is going.

Hitler, who might otherwise have faded out of history as just another square-mustached college dropout, picked up a copy of Zarathustra and was inspired to do a little more with his life. Some years later he distributed copies to his soldiers and went about arranging a big-budget live stage adaptation known as "the Holocaust."

What it's really about:

If Nietzsche wasn't too busy being dead, he would probably have had a few words with Hitler about the fuehrer's liberal interpretation of his work, due mainly to the fact that Nietzsche hung around with entirely the wrong crowd. His sister, Elisabeth, and good friend, composer Richard Wagner, were both as Nazi as the goose-step.

This portrait of Wagner comes courtesy of a dockside caricature artist.

After Nietzsche died, Elisabeth inherited the rights to his works and went about diligently re-editing them with a "kill all the Jews" subtext. It didn't help that Nietzsche's thought-baton was then picked up by the philosopher Martin Heidegger -- you guessed it: Nazi.

Nietzsche actually hated anti-Semites, having refused to attend his sister's wedding because she was marrying a Nazi, and even wrote that "anti-Semites should be shot." We have his sister to thank for the "blond beast" confusion. She, Hitler and decades of disapproving philosophy students interpret this as an allusion to the Aryan race. In fact, Nietzsche was just describing lions.

After all, does this look like the mustache of a racist?

And as for the "superman" thing, rather than referring to some genetically pure German dictator, Nietzsche was just making a generic statement about people who believe in the subjectivity of morals and seek to find their own values in the world -- a concept wholly incompatible with just following the whim of some guy with a hate-boner for some specific race. Interpreting Zarathustra's message as a call to raise an army and purge the world of undesirables is something akin to believing that Animal Farm was really a warning about farm animals taking over the world.

Wait, it isn't?

S Peter Davis writes for OxygenThieves and takes on 3,000 years of thought at Three Minute Philosophy.

For more regretful pioneers, check out 6 Geniuses Who Saw Their Inventions Go Terribly Wrong. Or learn about some masterpieces that the world loathed, in 6 Great Novels that Were Hated in Their Time.

And stop by Linkstorm to see some more misunderstood geniuses.

And don't forget to follow us on Facebook and Twitter to get sexy, sexy jokes sent straight to your news feed.

Do you have an idea in mind that would make a great article? Then sign up for our writers workshop! Do you possess expert skills in image creation and manipulation? Mediocre? Even rudimentary? Are you frightened by MS Paint and simply have a funny idea? You can create an infograpic and you could be on the front page of Cracked.com tomorrow!